Decrypting the nutritional label on your favourite packaged food products might get easier sometime soon. But that doesn’t mean you’re going to like what it’s going to say. (UNSPLASH)

“It’s sort of hidden.”

That’s how 30-year-old Elvina Moodley describes the nutritional labels on the back of packaged food products stacked on grocery store shelves. “When you’re there, you’re already in a rush and don’t have the time to look at the small print on the back to see how much sugar or salt is in an item.”

Moodley, like many South Africans, says she’s never really understood how nutritional tables — the per serving amounts of calories, glycaemic carbohydrates (carbohydrates the body digests and uses for energy), protein, fat and sodium (salt) — translate into what is a healthy, or unhealthy, food.

But big, bold triangle warning labels on the front of packages could mean making healthy choices will be a lot easier.

South Africa’s draft food labelling regulations, which are under review at the health department, would require packaged foods high in sugar, salt, saturated fat (often from animal fat or plant oils) or any amount of artificial sweetener to carry warnings for consumers.

It would work, says Edzani Mphaphuli, executive director of the childhood nutrition nonprofit Grow Great, in a similar way to warnings on cigarette packs.

“You might not know why smoking causes cancer, but when you see the label, you start to think, ‘Okay, this might not be good for me,’” she says. “But [many people] don’t know that sugar causes cancer or that obesity is related to cancer. We just think about it as, ‘I’m big,’ and it ends there. There isn’t a clear link that is made around that and hypertension (high blood pressure) and diabetes, and all of the other chronic diseases.”

Why labels are hard to read

Many familiar foods — from noodles and breakfast cereals to baby food — are considered ultraprocessed. It’s because of how they are made, using ingredients you wouldn’t normally find in a kitchen, such as artificial colours and preservatives. Often these foods are filled with sugar, fat, starch and salt. Those ingredients give people energy in the form of calories but fewer healthy nutrients like proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals. Eating too many of these types of foods can raise the chances of obesity, which can lead to diabetes, cancer and heart disease.

Currently, food labels in South Africa are required to list all product ingredients, including those that people could be allergic to, where the product comes from and its best before or use-by date. But unless manufacturers make claims like “low in sugar”, they don’t have to include detailed per serving nutrient information.

Even when it does appear, it’s often in small writing and uses terms and measurements that an ordinary shopper would not understand, says Makoma Bopape, a nutrition researcher and lecturer at the University of Limpopo.

“It tells you how much of certain nutrients you get in, say, 100ml or in a serving size. But if you don’t have a nutritional science [background] it’s hard to know what that means.”

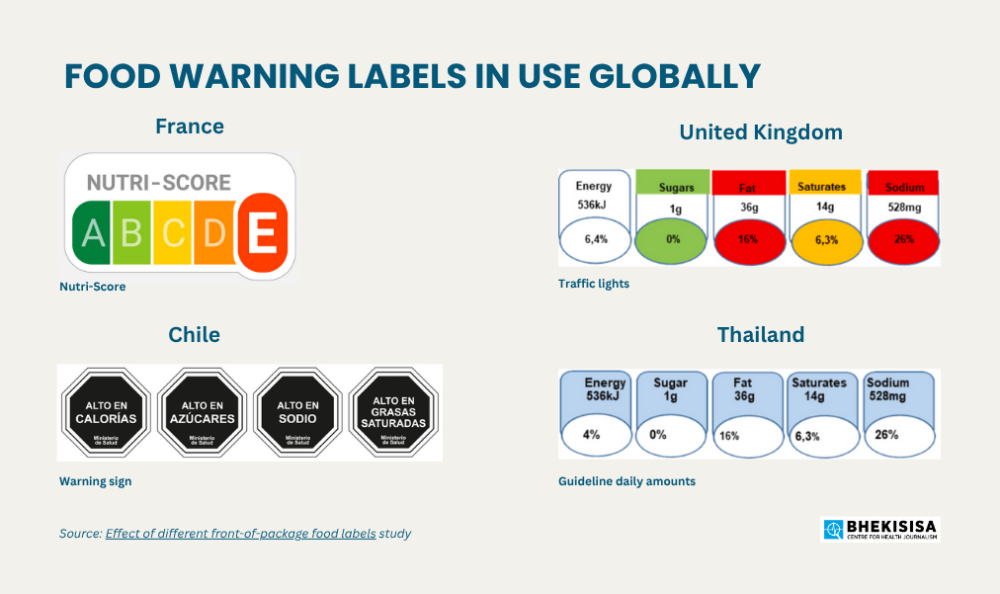

That’s why some countries have started to use simple front-of-pack labels. Since 2013, the UK has used a “traffic light” system with red, yellow and green markers to show whether a product is high, medium or low in sugar, salt and fat. While it is mandatory for manufacturers to include nutritional information on the back of their products, they can opt to use the “traffic light” on the front of food packages — and most do.

These labels help shoppers compare products, but they can also confuse them. A UK government report found that the colours can overwhelm shoppers with too much information.

A Chile warning

Not all front-of-pack labels are equal. Research shows that clear warning signs that simply say the food is “high in” sugar, salt or saturated fats are easier for people to understand than traffic lights — and work better at helping them spot unhealthy products.

Chile was the first country to introduce warning labels in 2016. A bold, black and white octagon — like a stop sign — appears on the packaging of foods high in calories, salt, sugar or saturated fats.

The result? After the regulations were enacted, Chileans bought fewer of these products and manufacturers put fewer unhealthy ingredients in cereals, dairy and sugary drinks. But in some cases, sugar was replaced with non-nutritive sweeteners (such as sucralose and stevia), which don’t lower the risk of obesity in the long run.

In 2021, Chilean researchers compared the ingredients of 999 products sold before and eight months after the law was introduced. They found that about a third of products that had less sugar to avoid a warning sign did so by switching to nonnutritive sweeteners.

Yet obesity rates continued to rise from an estimated 33.2% of adults with obesity in 2016 to 38.9% in 2022. The NCD Alliance, a global network which advocates for policies on noncommunicable diseases, says that while Chile’s warning labels are an important way to help people make healthier choices, poverty and lack of access to healthy food make a healthy diet difficult to maintain.

In France, manufacturers use what’s called Nutri-Score, a grading system which ranges from a green A to red E. The score adds points for nutrients like fibre and protein and subtracts points for unhealthy ones. So, a high sugar and low fibre cereal would carry an orange D, but a low sugar and high fibre one would have a green A.

South Africa will use a similar system to Chile, but the label will come in the shape of a triangle. Studies found the triangle, like those used in road signs to signal danger, is the easiest for South African shoppers to relate to.

The warnings will cover between 10% and 25% of the front of the package, will be black on a white background and will be located in the top right corner. They will have the words “high in” and “warning” in bold, uppercase letters, next to an exclamation mark and an icon to represent the nutrient. This will help make the warning easier for people who can’t read or don’t speak English to understand.

Because each nutrient will have its own warning symbol, if a product is high in more than one nutrient — or has any artificial sweeteners at all — a single package could carry up to four warning icons.

‘They just want to fill their tummies’

Still, what people — and their children — eat isn’t always up to them, says Mphaphuli. “Some parents can only afford cheap food that fills up the family the quickest, which limits their choice in what they consume.”

In 2021, around 3.7-million (20.6%) of South Africa’s 17.9 million households said they didn’t have enough food for a healthy diet. Over half a million families with children younger than five reported going hungry.

Most of these households are located outside of the metropolitan areas, where healthy, nutrient-rich foods — like fruits, vegetables and nuts, which are high in protein, vitamins, minerals and fibre — are both expensive and harder to come by, says Mphaphuli.

“If in your spaza shop one apple costs the same as a bottle of highly concentrated juice that can be shared across days, you’re going to go for the cheaper thing.”

When people don’t have enough types of food to choose from, they buy what lasts longest — even if it isn’t healthy. Many homes survive on processed cereals, condiments, oils, sugar and fats.

“People say, ‘At the beginning of the month, when I still have money, I get worried and I pay attention to what I buy. But as the month goes by, I just buy whatever I can afford,’” explains Bopape. “They just want to fill their tummies.”

Clear labelling alone won’t be enough to reduce unhealthy eating, says Bopape. Warning signs need to go hand in hand with other policies such as sugar taxes, restrictions on advertising and the selling of unhealthy foods in and around schools.

Moodley wishes healthy foods were more reasonably priced. But the warning labels will at least “help us know what we’re getting ourselves into”.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.