House of cards: Despite constitutional assurances of gender equality and the right to housing, women find themselves up against patriarchal norms, unequal treatment under customary practices and little protection from the law. Photos: Seri

A new report has found that South Africa is failing to uphold women’s rights to land and housing, despite constitutional protections and international legal commitments.

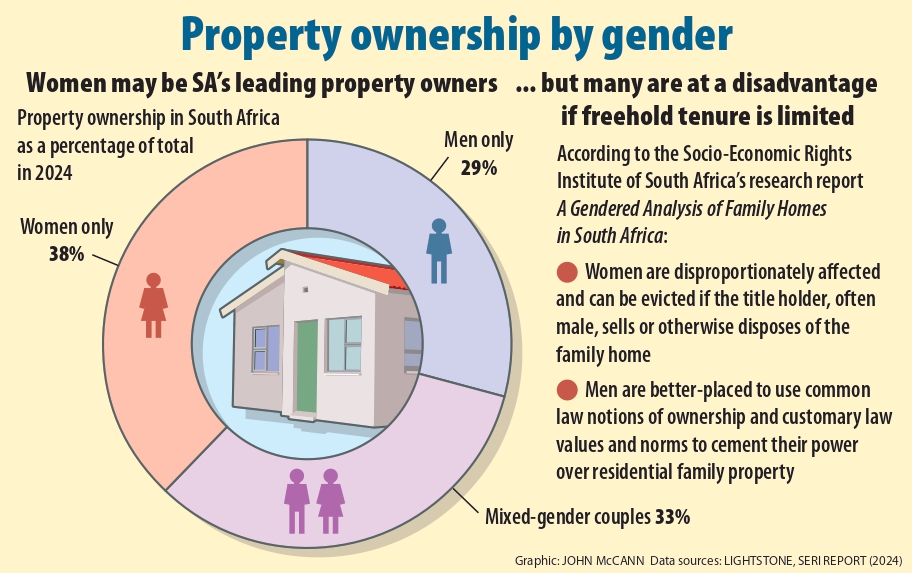

The 52-page shadow report, compiled by the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (Seri) and the Women and ESCR Working Group of the International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, outlines widespread discrimination against women regarding access to housing and security.

The report paints a bleak picture of women facing entrenched patriarchal norms, unequal treatment under customary law and weak enforcement of legal safeguards.

“We are not illegal occupiers. We are mothers, workers, survivors — this land is the only place we have,” said Thoko, a resident of an informal settlement outside Durban, who did not want to give her real name.

She has faced constant eviction threats for more than 10 years, despite calling the settlement home.

The Constitution guarantees gender equality and the right to housing, while laws such as the Extension of Security of Tenure Act and the Prevention of Illegal Eviction Act aim to protect the vulnerable from being removed without legal process.

But the report outlines that land and housing policies often prioritise married, male-headed households. Women living in informal settlements, farming areas and urban townships find themselves sidelined by a system that continues to see them as dependents, rather than rights-holders.

“Women are treated as invisible in housing policy. You only matter if you are someone’s wife,” a community organiser with the Land and Accountability Research Centre.

“And if your husband dies or leaves, you can lose everything.”

Interviews with residents of Slovo Park, Johannesburg and in Cato Crest in Durban found that in rural areas under traditional authorities women often can’t get land because of patriarchal customs.

“Land allocations are rarely given to single women and those without male relatives often face social stigma and institutional exclusion,” the report said.

It states that evictions go beyond simple relocation — they cause traumatic breaks that hit women harder than men. It shows that authorities often evict households led by women multiple times, often without proper court orders. The removals not only strip women of shelter but also their safety and dignity.

“They came at 4am and started tearing down my shack while my children were still sleeping,” recalled Zanele, a domestic worker in Gauteng, who also did not want to be named. “I have nowhere else to go and every week they come back with more threats.”

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The report points out that city teams tasked with stopping land grabs often use force and scare tactics and wreck the property of women living in makeshift camps. Yet accountability remains elusive.

Migrant and refugee women, especially those who are undocumented or awaiting asylum claims, face even greater obstacles. Barred from state housing support, and often discriminated against by landlords, they remain in legal and social limbo.

“We don’t ask for special treatment — just to live without fear,” said Amina, an asylum-seeker from the DRC in Joburg. “But they treat us like criminals for trying to survive.”

The report added that housing policies ignore the specific struggles of migrant women, despite the Constitution promising housing rights for all.

The report highlights a major issue — national housing programmes lack data separated by gender. This missing information makes it difficult to judge how policies affect women or whether efforts to close the gender gap in housing and land access are working.

The report calls for a gender-focused strategy in housing and land reform requiring joint ownership in government housing projects, securing women’s rights to use customary land and ensuring accountability by gathering data and changing laws.

South Africa is set to meet the UN committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights later this year. It will review how countries are meeting their responsibilities under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which South Africa signed in 2015.

“Women’s rights to land and housing are not just legal issues — they are life and death,” said Seri executive director Nomzamo Zondo at the launch of Seri’s sister report A Gendered Analysis of Family Homes in South Africa in August last year.

“We need a state that sees women, not as appendages to men, but as citizens in full.”

The new report women’s equal rights in housing warns about how urban growth and planning rules have created gender-based exclusion. In many cities, authorities carry out evictions under the guise of upgrades and “cleaning up” of urban spaces, which has hit women-led households in informal areas and urban centres the hardest.

The removals often happen without offering new housing that considers women’s caregiving needs, school access and closeness to jobs.

Shack dwellers movement, Abahlali baseMjondolo said: “We’ve seen women pushed to the edges of cities where there’s no transport, no clinics or schools. This is a planned form of displacement.”

The report urges an immediate need to revise how government housing is allocated.

“Current systems often work against single women, queer people or domestic violence survivors who cannot show proof of cohabitation or nuclear family ties,” it said.