Culpable homicide: The Quantum was allegedly attempting to overtake

four vehicles when it collided head-on with an oncoming truck. Twelve

learners were killed. Photo: Timothy Bernard/Independent Newspapers

The morning 17-year-old grade 11 learner Puleng Maphalla died began ordinarily.

She woke up on time. The scholar transport minibus collecting schoolchildren from the Vaal arrived a few minutes late, her father would later explain. Not Maphalla.

There was no rush and no sense of urgency. This was a paid, routine service transporting pupils to school. One that parents are expected to trust.

Hours later, Maphalla was among 12 learners killed when the minibus they were travelling in collided with a truck on Fred Droste Road near Vanderbijlpark, south of Johannesburg, shortly after 7am on Monday.

Twelve learners were killed at the scene. Two others, who had sustained critical injuries, died in hospital in the early hours of Thursday 22 January, bringing the death toll to 14.

Maphalla attended El Shaddai Christian School. She loved church, her father said. She sang. The night before the crash, they had been together at a service.

Nothing about the morning suggested it would end differently from any other school day.

When her father arrived at the crash site, he said he could not recognise the vehicle as a vehicle. It had disintegrated. Children lay scattered across the road. Maphalla was not there. He would identify her only later, at the mortuary.

Speaking to SABC News from the scene, he rejected the language that often follows such tragedies.

“I didn’t see an accident,” he said. “I saw murder.”

The interview, broadcast live and widely shared, travelled far beyond the initial news cycle. It lingered after the official statements, arrests and condolences had settled. Its persistence reflected a deeper public discomfort. This was not a tragedy that could be easily explained away as misfortune or error.

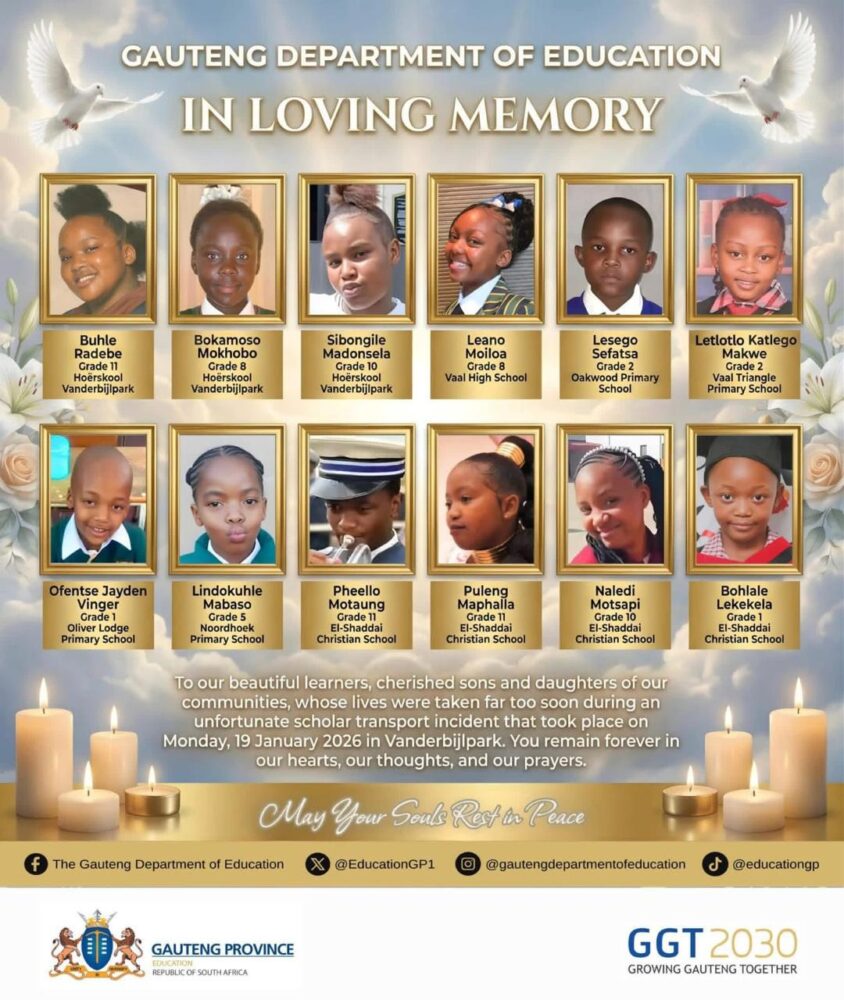

The Gauteng department of education named the other 11 victims as: Buhle Radebe (Grade 11), Bokamoso Mokhobo (Grade 8), Sibongile Madonsela (Grade 10), Leano Moiloa (Grade 8), Lesego Sefatsa (Grade 2), Letlotlo Katlego Makwe (Grade 2), Ofentse Jayden Vinger (Grade 1), Lindokuhle Mabaso (Grade 5), Pheello Motaung (Grade 11), Naledi Motsapi (Grade 10) and Bohlale Lekekela (Grade 1).

They attended Hoërskool Vanderbijlpark, Vaal High, Oakwood Primary, Vaal Triangle Primary, Oliver Lodge Primary, Noordhoek Primary and El-Shaddai Christian School.

The names of the latest two fatalities had not been published by the time of going to print.

In its official form, the story initially followed a familiar arc.

Police said the minibus driver attempted to overtake multiple vehicles on a narrow stretch of road before colliding with an oncoming truck.

The driver was injured and taken to hospital. A case of culpable homicide was opened.

That account shifted sharply the following day.

Gauteng Premier Panyaza Lesufi confirmed that the driver’s professional driving permit had expired in November last year, meaning he was not legally authorised to transport learners at the time of the crash.

Gauteng police spokesperson Mavela Masondo later confirmed that the driver was arrested after being discharged from hospital.

On Thursday, the driver, Ayanda Dludla, appeared before the Vanderbijlpark Magistrate’s Court. The 22 year old now faces 14 counts of murder and three counts of attempted murder, as well as charges of driving without a valid professional permit and operating an unlicensed vehicle. The matter was postponed to 5 March 2026 for further investigation. Magistrate Claudia Venter presided, with Daniso Titus appearing for the state.

The driver of the truck involved in the collision was not injured, while a passenger sustained injuries and was receiving treatment.

The escalation of charges marked a decisive shift in how the state is framing responsibility. What initially appeared to be a case of negligent driving has come to be treated as a far more serious breach, rooted in unlawful operation and systemic oversight failure.

The confirmation that the minibus was being operated illegally altered the nature of the tragedy. What initially appeared to be a case of dangerous driving now pointed to a more fundamental failure of oversight.

Five days before the crash, ahead of the reopening of schools on 14 January, Gauteng traffic police had warned scholar transport operators to comply with safety regulations.

Vehicles transporting learners, officials said at the time, were required to be roadworthy, regularly inspected and driven by individuals holding valid professional permits. Drivers were expected to comply with speed limits and traffic laws.

After the crash, the warnings hardened into enforcement language. The Gauteng department of community safety announced a zero-tolerance approach for the 2026 school term, with intensified law enforcement operations around school routes.

Lesufi underscored the message plainly. Children, he said, must never be treated as cargo.

By then, 14 children were dead.

The expired permit does not, on its own, explain how a vehicle carrying schoolchildren continued to operate openly and daily without intervention.

It does, however, expose a deeper regulatory failure that extends beyond one driver or one route. Responsibility for scholar transport safety in South Africa is fragmented. The department of basic education is responsible for learner welfare but does not regulate vehicles or drivers.

Transport authorities oversee licensing and roadworthiness.

Traffic police enforce behaviour on the roads. Criminal justice processes intervene after lives have been lost. No single institution carries end-to-end accountability for ensuring that a child’s journey to school is safe.

The fragmentation is most visible in the private scholar transport sector.

Private operators fill gaps left by inadequate public provision, particularly in peri-urban communities. Yet they operate within a permissive regulatory environment, absorbed into the broader taxi system despite transporting children. Monitoring is inconsistent.

Enforcement is uneven. Failure is often identified only after tragedy occurs.

Warnings about this system are not new.

The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) has repeatedly raised concerns that unsafe scholar transport conditions amount to violations of learners’ rights to life, dignity and education.

Investigations have documented weak oversight and poor coordination between departments.

Despite this, reform has been slow and sporadic. Risk has become normalised.

On Monday, the day of the Vanderbijlpark crash, the SAHRC published a report on systemic scholar transport challenges in the North West province which identified pervasive failures in the scholar transport system.

It said those were characterised by “the use of unroadworthy and unsafe vehicles, including buses with mechanical defects, expired discs, fuel leaks, inadequate safety features and in some cases, described as ‘coffins”.

The report also highlighted chronic overcrowding and multiple-trip operations which caused late arrivals, missed lessons and learner exhaustion, frequent breakdowns leaving learners stranded or forced to walk long distances and lack of supervision during transportation which exposed learners to bullying and safety risks, especially where young and older learners travelled together.

For many families, scholar transport is not a choice but a necessity. That reality limits parents’ ability to interrogate permits, roadworthiness or compliance.

Trust becomes the default position. When that trust collapses, the consequences are devastating.

Infrastructure further compounds the danger.

The road where the crash occurred is known for heavy truck traffic. Poor lighting, limited traffic calming measures and inconsistent enforcement increase risk even in lawful conditions.

When unlawful operations are added, the danger becomes acute. Road safety interventions along learner transport routes are not optional. They are essential protections for children.

The impact of the crash has extended beyond schools and immediate families.

In a statement, the Vaal University of Technology said the tragedy had profoundly shaken the broader community it serves. It noted that the learners who died formed part of a shared social fabric shaped by education and aspiration.

The university confirmed it had activated counselling and psychosocial support services for affected families, learners and community members during what it described as a period of collective grief.

“Beyond this specific tragedy, the vice chancellor expresses grave concern about the continued carnage on South Africa’s roads, particularly incidents involving scholar transport,” it added.

It noted that figures released by the department of transport showed more than 11 000 people lost their lives on the country’s roads in 2025, “underscoring an ongoing national crisis that demands renewed urgency, accountability and collective action to protect the most vulnerable road users, especially children”.

That response illustrates how learner deaths reverberate across entire educational ecosystems. Scholar transport tragedies disrupt classrooms, strain teachers, overwhelm families and expose how closely schools, tertiary institutions and communities are linked.

The regulatory fallout has since widened.

The Scholar Transport Association announced that its members would not transport learners to school on Friday, pending the resolution of permit compliance issues with government. The association said it would hold a briefing to outline its position and the steps required to regularise operations.

Yet South Africa’s response to road fatalities involving children follows a familiar pattern. Psychosocial support is mobilised. Statements are issued. Calls for safer roads are renewed. What remains absent is a sustained shift in how risk is managed before tragedy occurs.

Children reliant on scholar transport remain among the most exposed road users. This is not a failure of awareness. It is a failure of prioritisation. The Vanderbijlpark crash exposes the gap between constitutional promise and lived reality.