(Canadian Museum of Human Rights (CMHR) / Aaron Cohen)

At a time when the globe is confronted with perpetual challenges of various forms of injustices which have been made more visible by the Covid-19 pandemic, museum spaces force people to pause and reflect on the past while imagining a possible just future.

Artistic visual images are useful tools that can be used to represent people’s stories of oppression, suffering, resistance, liberation, survival and healing. Artworks can be used purposefully to mediate reality in a “performative” way and, furthermore, they allow for both individual and collective emotional response.

Art has and continues to play a critical role in the promotion of human rights and the positive transformation of societies both during and in the aftermath of mass atrocities.

In 2019, the Auschwitz Institute for the Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities (AIPG) selected six artists and collectives from countries with histories of mass atrocities to be part of the Artivism: The Atrocity Prevention Pavilion exhibition at the Venice Biennale. AIPG was invited by The Biennale Foundation to show the intersection between art, human rights and the prevention of genocide — the first in the Biennale’s 124-year history. Real-life examples of art being used to further peacebuilding and transitional justice in post- and mid-conflict societies were exhibited.

According to Kerry Whigham of the AIPG, the exhibition “displayed the quintessential role that the arts play, particularly as a grassroots tool for social transformation and the prevention of systematic violence. More than merely showing the way others have used the arts to foment positive change, AIPG’s exhibition also provided concrete steps for visitors themselves to take action, highlighting their own power to play a role in mass atrocity prevention at home and around the world”.

This was done through the 60/60/60 initiative where visitors were asked to give either 60 seconds, 60 minutes or 60 days towards preventing such atrocities.

“Atrocity prevention happens at the interpersonal, individual level. We all have something to contribute,” says Whigham.

(Canadian Museum of Human Rights (CMHR) / Aaron Cohen)

(Canadian Museum of Human Rights (CMHR) / Aaron Cohen)

The exhibition moved to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) in Winnipeg, where it will run until January 2022. The hope is that the artworks will continue affording a space for reflection, contemplation and understanding of the various complex histories of mass atrocities, displacements, and other various forms of oppression.

The six projects included are:

• Što Te Nema [Why Are You Not Here?] by Bosnian artist Aida Šehović. It is a travelling memorial to commemorate the 8 000+ victims of the 1995 genocide in Srebrenica. Visitors are invited to fill a cup of Bosnian coffee and leave it in the square of a city visited to remember those who can no longer join their families for coffee. Šehović ’s coffee cups are displayed;

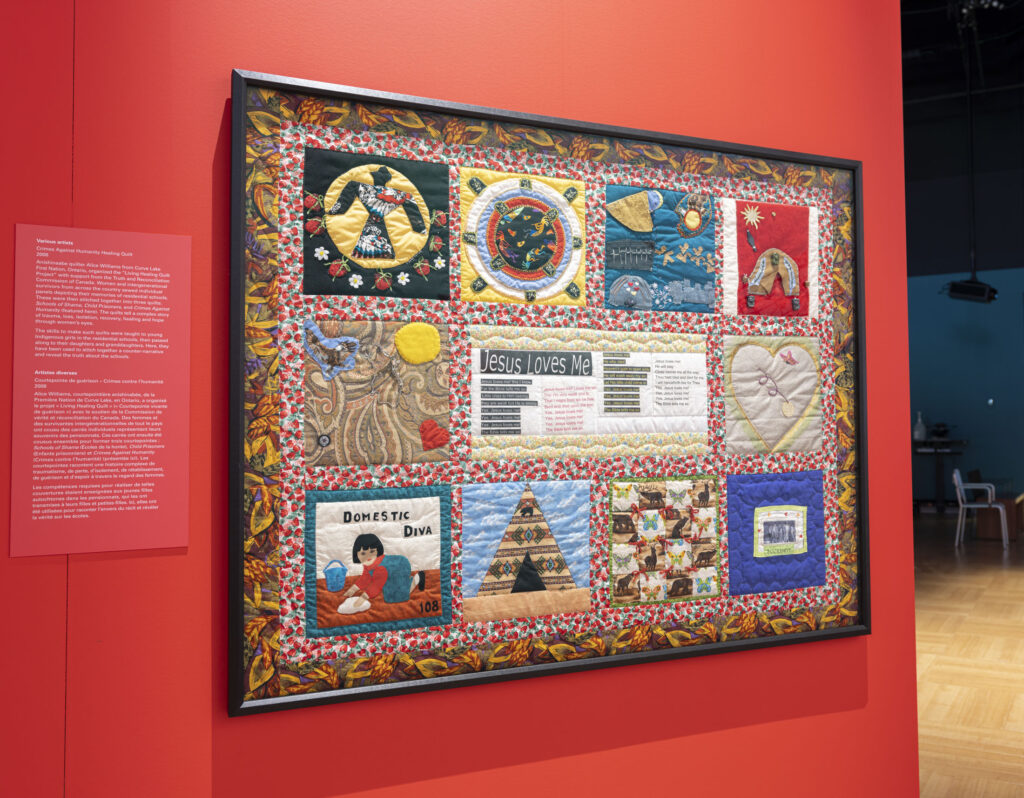

• A selection of objects collected by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) from survivors of residential schools;

• The Intuthuko Embroidery Project from South Africa. In the aftermath of apartheid, a collective of black women were looking for a way to tell their stories about life during this period of state-led oppression. They began gathering together to embroider their testimonies onto fabric;

• A collection of more than 20 masks created by Iraqi artist Rebin Chalak shows the faces of Yazidi women who were persecuted, but survived violence under Isis;

• Oleh-Oleh [Souvenirs] is a sound installation from Indonesian artist Elisabeth Ida. It depicts 13 rows of 13 ears to represent the 13 activists who were captured by the Indonesian government in the 1990s and have still not been returned. In the past, perpetrators in Indonesia have been known to cut off the ears of victims as a souvenir or trophy of their kill; and

• A collection of street signs that were created by Argentinian street artists to point out the location of unpunished perpetrators from the military dictatorship of 1976-1983.

Housed alongside the exhibition at this museum is The Witness Blanket, an art installation by master carver Carey Newman (Hayalthkin’geme) which is a commemoration of all those who passed through the Canadian residential school system, and those who never made it out.

The work resembles a woven blanket crafted from cedar blocks threaded on wires and adorned with about 800 items collected from residential school sites, survivors and families.The churches and federal government also donated pieces as a gesture towards reconciliation.