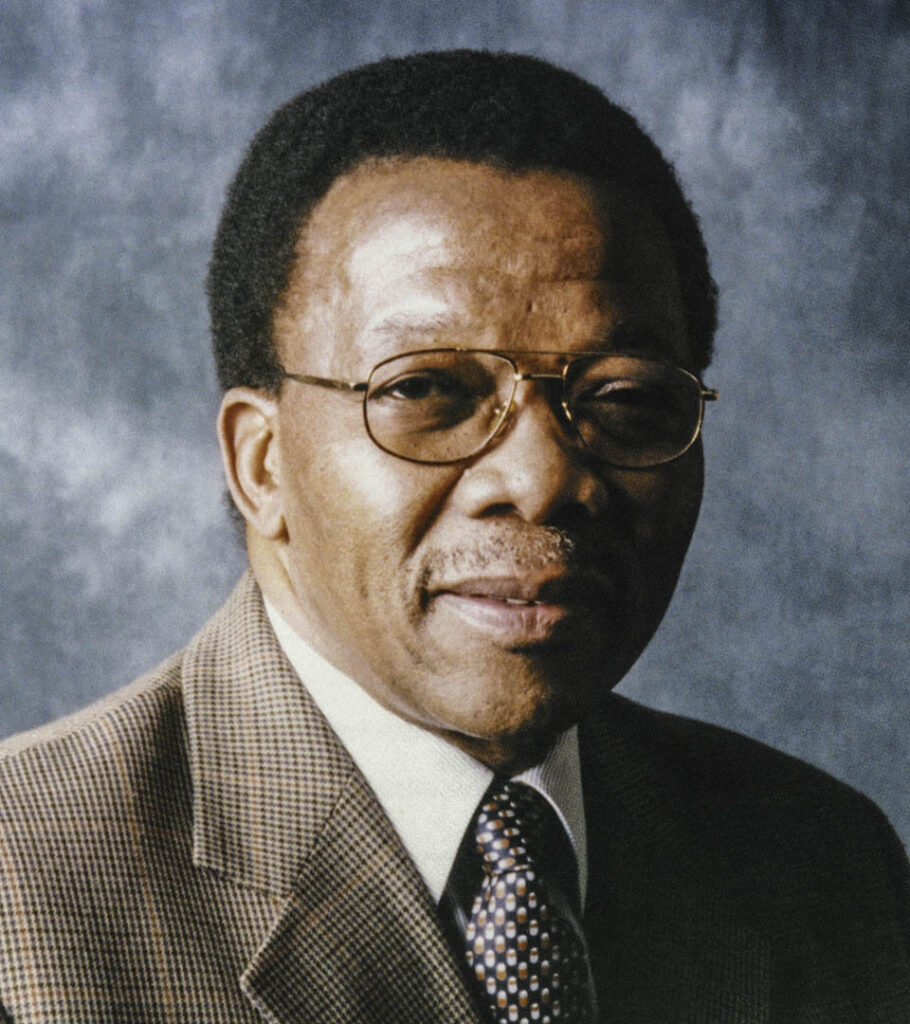

Lessons: The orature of Zulu poet DBZ Ntuli helped researchers collate oral environmental knowledge. (Universal History Archive/Getty)

Two lecturers from the University of the Free State are researching ways to localise and make accessible terminology and knowledge related to climate change and the environment.

Dr Oliver Nyambi, a senior lecturer in the English department, and Dr Patricks Voua Otomo, a senior lecturer in the department of zoology and entomology, are doing research to examine the portrayal of environmental conversation in oral stories from indigenous South African cultures. The study is titled Environmentalism in South African Oral cultures: An Indigenous Knowledge System Approach.

“The project is about indigenous South African oral cultures as a potential knowledge system where indigenous forms of environmental awareness are simultaneously circulated and archived,” Nyambi told the Mail & Guardian.

“Our main interest is on how we can understand folk oral stories about humanity’s interactions with the environment as creating possibilities for knowing how traditional societies consciously thought about environmental concerns and set out to conserve and preserve plant and animal species to sustain ecological balance.”

“We envision our research to spotlight the potential but currently untapped utility of oral cultures in conservation. Our field work in KwaZulu-Natal revealed a rich tradition of environmental knowledge, environmental awareness and nature conservation which is mediated and transmitted through folk stories.”

The research is based mostly on oral cultures but includes more context-specific terms.

“We have been reading and writing on the orature (written oral poetry) published by Zulu poet Deuteronomy Bhekinkosi Zeblon Ntuli who has used the phrase “imvunge yemvelo” (the humming sounds of nature) – a metaphor of nature, which maps its importance in aesthetic terms of pleasant and soothing melodies made by birds,” Nyambi said.

The duo’s first paper has been accepted by the journal African Studies Review and is to be published later this year.

Otomo said it was of concern that indigenous oral story traditions and the associated and “underestimated” folk wisdom were dying out. These could be used in “the urgent process of decolonising and re-thinking environmentalism”.

Zulu poet DBZ Ntuli

Zulu poet DBZ Ntuli

“Secondly, we felt that by combining our expertise in entomology and cultural studies, we could set up a uniquely transdisciplinary methodological, conceptual, and theoretical toolkit that could make, in new ways, knowledge about environmentalism in indigenous South African oral cultures.”

Otomo said there had been no work done by scholars that looked at African oral cultures and more especially at the genre of climate and environmentalism.

“Scholars and publishers have placed more interest on modern forms and genres of story-telling such as the novel and film,” he says.

“There must be a deeper understanding, for instance, about what the animals, trees, and rivers mean or signify in most indigenous totemic praises and (clan) names. The same can be said about oral folk stories and songs.”

“They are products of group awareness of the environment and their philosophies of conservation are as valid today as they were [during] their creation in antiquity, Telling these stories doesn’t only keep them alive, it keeps their meanings and intentions alive,” Otomo explained.

Chris Gilili is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for South Africa