Deadly: Mitigation measures will cut injuries and fatalities of birds that come into contact with power lines (left) and wind turbines. Photo: VulPro

In the past month alone Kerri Wolter and her team have responded to multiple vulture emergencies: birds with severe burns, broken wings and other injuries after they collided with power infrastructure.

“These magnificent birds arrive barely clinging to life,” said the chief executive and founder of the vulture conservation organisation VulPro. “Without immediate intervention, none would survive.”

Power lines and wind farms continue to devastate the country’s critically endangered vulture populations, she said.

Expanding human development increasingly encroaches on their habitat, resulting in these “beautiful and misunderstood birds” being maimed or killed.

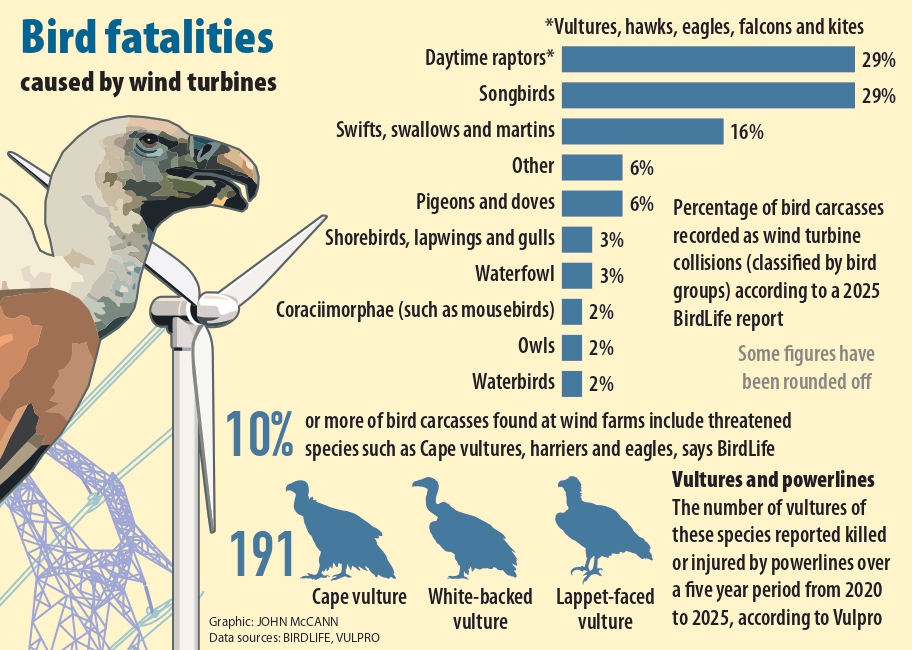

Recent data from VulPro has shown the scale of the problem: 191 vultures — Cape vultures, white-backed vultures and lappet-faced vultures — were reported dead or injured from 2020 to 2025 because of power lines.

“That excludes what other organisations, members of the public, landowners and farmers are picking up. So, that is only actually a fraction of the reality,” said Wolter.

“We estimate that that figure is probably only 10% of the actual reality.”

In a single year, about 40 vulture fatalities were recorded from power line incidents, with an average of three vultures a month lost to electrocution or collision.

Since VulPro’s inception in 2007, it has recorded 473 fatalities. But these figures probably under-represent the true mortality rates, because many incidents go unreported.

The crisis extends beyond Cape vultures to include other endangered species such as white-backed and lappet-faced vultures, Wolter said. With some vulture populations having plunged by more than 90% in certain regions, “every individual bird becomes crucial for species survival”.

Collisions with power lines and wind turbines and electrocutions occur when vultures have to navigate many obstacles on their way to find food and roosting spots.

Roosting birds may cause a short circuit on the power lines when they defecate. During severe storms they may be blown off their pylon perches into the cables.

Vultures sometimes fly into the cables because they are difficult to see. These collisions can cause broken wings or legs and even electrocution. Regarding wind turbines, the blades move fast and a vulture thermalling nearby may be carried into their path.

Over the years, VulPro has worked closely with Eskom and other authorities to find ways to implement mitigation measures at power lines.

That fatalities are rising is a frustration for VulPro because power lines are a mitigable threat, Wolter said.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

“It’s not like poisoning, which is incredibly difficult and almost impossible to mitigate against.

“It [power lines and wind turbines] is a threat, that if addressed, the benefits that will have to vulture populations in the country is huge. And it could single-handedly be a game-changer for the survival of some species.”

The biodiversity management plan for vultures — which VulPro played a pivotal role in establishing — was finalised in 2022. Although the management plan framework is a crucial step forward, its implementation has been hampered by systemic problems, Wolter noted.

“We continue to work with government agencies to strengthen implementation, but the urgency of the vulture crisis requires accelerated action from all stakeholders.

“The government needs to take Eskom to task as to why there is not more being done. Eskom has to give us reports and in those reports we have to see what has been investigated, what has been closed and what has been addressed.

“The number of incidents that they closed but they have not addressed is huge.

“Their excuse is they don’t know how to change it, or there needs to be more research or it’s an isolated incident and they’ll monitor it. This is where the government does need to step in to say power lines — collisions, electrocutions — is a threat that, if addressed, will have huge implications for the survival of vulture species.”

Mitigation measures include making power lines more visible to avoid collisions.

“There’s evidence that has shown that it works,” Wolter said.

“As human beings we don’t want to see them but we want these lines to look like Christmas trees, because the more visible they are, the less dangerous they are for the kings and queens of the sky. We don’t own the skies, the birds own the skies.”

Once a structure is up, it is costly to mitigate the effect of the power lines, she said. “There is a financial implication with Eskom and we understand that. I think our biggest issue is why isn’t it being done on every single line that goes up?

“It has to be mandated where any line that goes up — be it a municipality, be it a transmission or a distribution line or whomever it belongs to — needs to be well marked for those that are using our skies.”

Bird guards are another mitigation method that are retrofitted over existing structures, helping to avoid electrocutions.

“And, again, that works,” said Wolter. “The issue we have with those is that, in time, they fall off and they need maintenance and Eskom obviously doesn’t have the finances or capacity to maintain every single structure in the country.

“Our belief is that all structures, new and old, should always be bird-friendly [but] once again what happens is that they wait for the structures that need to be replaced and only then will the new structures come into play.”

Wolter said that for the biodiversity management plan to succeed, government entities must enforce regulations and provide funding; all conservation organisations involved need to conduct research, rehabilitation and community education; and private landowners should preserve habitats and report incidents.

In addition, traditional leaders need to promote sustainable practices that reduce demand for vulture parts; the energy sector should retrofit infrastructure with bird-safe designs and conduct thorough impact assessments and academia needs to study population dynamics while developing conservation training programmes.

As of this year, of the 538 incidents that were reported, only 276 have been adequately addressed, while another 134 remain open and pending investigation and 279 have been closed but with questionable outcomes, Wolter said.

Without accurate reporting, data gaps are emerging. Electrocutions and collisions have risen by 1 166%, from three in 2012 to 38 in 2024.

Furthermore, rescues to save vultures from the trade in their parts for belief-based purposes now occur almost daily.

Amid these problems, some renewable energy operators are pioneering solutions.

Wolter singled out the Golden Valley wind farm in the Eastern Cape, which has implemented comprehensive vulture protection measures at its 48 turbines.

These include cutting-edge bird detection technology, buffer zones around nesting sites and seasonal operational adjustments during migration periods.

“They recognise their responsibility to generate clean energy without compromising biodiversity,” Wolter said. “Their monitoring data shows a significant reduction in vulture mortality since implementing these measures, proving that renewable energy and conservation can coexist when proper precautions are taken.”

With the renewable energy market in South Africa poised to reach 20.06 billion kilowatt-hours this year, vultures remain vulnerable.

“One must remember that … as wind farms grow, there are more power lines.”

Wolter said that for any wind farm that is in operation or that is being developed, the government needs to enforce shutdown-on-demand to prevent vulture fatalities.

VulPro’s multifaceted approach demonstrates that effective interventions are possible, with power line surveys identifying high-risk structures, retrofitting of dangerous power lines reducing electrocution rates, and bird flight diverters decreasing collision mortality by up to 92% globally, she said.

For example, recommendations have been made to fit the Lydenburg-Sabie 132 kilovolt power line with bird flight diverters to prevent collisions and install bird guards to minimise electrocutions.

“Every vulture matters,” Wolter said. “Our integrated approach of rescue, breeding, research and education aims to not only save individual birds but strengthen wild populations while advocating for the systemic changes needed across all energy infrastructure. But we cannot do this alone. We need all stakeholders to do their part.”

The South African Wind Energy Association (Sawea) told the Mail & Guardian that the wind industry is committed to responsible development by applying best practices in avifaunal mitigation and collaborating with conservation organisations.

Environmental impact mitigation, particularly avian conservation, is a key priority, championed through Sawea’s project development standing committee, it said. “Within this structure, the dedicated birds and renewable energy task team actively develops and advances avifaunal protection strategies.”

This is focused on standardising mitigation techniques to minimise bird collisions; developing and refining blade patterning and avifaunal mitigation guidelines in partnership with key stakeholders; and encouraging knowledge-sharing and best-practice implementation among industry players, said Sawea.

It said it strives to maintain good relationships with key stakeholders, including BirdLife South Africa (BLSA), and Sawea has “maintained a strong working relationship with BLSA for several years”.

Key milestones in this partnership include a joint issuance in 2023 of a briefing note on blade patterning, outlining key considerations for wind farm developers, environmental consultants and decision-makers.

Last year, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed with BLSA to enhance coordinated engagement and collaboration on biodiversity protection.

“The key priority areas guiding this MoU include, but are not limited to:

- Foster collaboration and exchange of relevant information to support the responsible development of wind energy projects in South Africa, ensuring communication between stakeholders.

- Provide technical support, share expertise, and actively engage in research, innovation, and resource mobilisation to achieve common objectives, including addressing the impacts of wind energy on avifauna.

- Recognise and promote excellence in environmental practices, while encouraging participation in workshops and events to raise awareness and encourage dialogue on wind energy’s role in energy transition and biodiversity conservation.

- Facilitate cooperation with local and regional organisations, promoting a unified approach to energy transition, climate change mitigation, and sustainable development, with a particular focus on South Africa and Africa.”

In 2024, Sawea and BLSA jointly developed blade patterning guidelines aimed at reducing bird collisions with wind turbines. “These guidelines recommend specific patterns and colours to enhance blade visibility to birds, thereby decreasing the risk of collisions. Sawea actively encourages members to implement avian protection strategies, including participation in research-driven conservation initiatives.”

Some of the key mitigation measures adopted within the industry include blade patterning. “Sawea applied for and obtained an alternative means of compliance (AMoC) approval from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) in January 2024 to allow industry members to pattern the blades on their wind turbines as a bird strike mitigation technique.

“The CAA have approved a number of applications for blade patterning from developers following the AMoC approval which illustrates industry’s commitment to explore the latest methods to prevent bird fatalities.

“We are actively promoting the adoption and exploration of various artificial intelligence (AI) technologies designed for avifaunal strike mitigation. These technologies aim to detect bird movements, through camera footage, in real-time and implement measures such as turbine shutdowns to prevent potential collisions.”

Sawea maintains ongoing collaborations with BLSA and other stakeholders “to ensure our members are well-informed and equipped with the latest knowledge and data,” it said, adding that this collaboration facilitates compliance with environmental standards and promotes the adoption of best practices within the industry.

Other key mitigation measures include the shutdown-on-demand (SDOD) strategy, which involves temporarily halting wind turbine operations when at-risk bird species are detected nearby.

“Initially reliant on human observers, SDOD has evolved to incorporate advanced technologies such as radar, camera systems, GPS transmitters, geofencing [and] AI to monitor bird movement and migratory patterns in real-time, enhancing the effectiveness and responsiveness of turbine shutdowns.”

Further key mitigation measures include acoustic deterrent devices, which emit ultrasonic frequencies designed to deter, for example, echo-locating bats from approaching wind turbines, thereby reducing collision risks.

Advanced radar systems provide continuous monitoring of bird and bat activity around wind farms, detecting and tracking movements. “These systems enable real-time data collection on flight patterns, altitudes, and behaviours, facilitating informed decisions to minimize avian collisions.”

Sawea said it supports conservation projects that involve tagging and monitoring endangered bird species, such as the black harrier raptor, to better understand their movement patterns and interactions with wind farms.

“This data informs the development of targeted mitigation measures to reduce collision risks and enhance species protection. Sawea remains committed to fostering a sustainable and responsible wind energy industry that aligns with South Africa’s conservation priorities.

“Through continued collaboration, innovation, and regulatory engagement, we strive to balance renewable energy development with biodiversity protection,” it said.

Eskom said its environmental management practices are undertaken in pursuit of its value of zero harm, “the prevention of harm to people and the environment. “One of our material environmental impacts is that of bird injuries and mortalities due to our electricity infrastructure and therefore a multitude of controls are in place to reduce this risk.”

The utility said it remains “deeply concerned” about the growing threats to South Africa’s vulture and other vulnerable bird populations, particularly the dangers posed by powerline collisions and electrocutions.

“With over 400 000km of transmission and distribution lines crossing diverse ecosystems, we recognise the risks and remain committed to actively safeguarding avian wildlife, especially critically endangered species such as the Cape, white-acked, and lappet-faced vultures. Our efforts continue to focus on mitigation strategies that protect these vital species.

“We recognise that vultures serve an important ecological role as nature’s clean-up crew and that their decline has far-reaching environmental consequences. The safety of these iconic birds is not only a biodiversity issue but a national conservation imperative.”

Eskom said it has worked closely with leading conservation organisations, including VulPro, the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) and BirdLife South Africa, to identify, mitigate and reduce the impact of its infrastructure on avifauna in the past 30 years.

“These partnerships are central to the implementation of preventative measures, such as the design of the power line structures, routing of powerline corridors and the proactive and reactive measures taken to reduce the impact.”

Among the key measures it had undertaken to mitigate the impact include:

• Proactive retrofitting: Since 2016, Eskom has retrofitted more than 23 000 high-risk structures across the country with bird flight diverters and raptor protectors, significantly reducing collision and electrocution incidents in priority areas.

• Risk-based modelling: High-risk zones are identified using avian risk mapping tools developed in collaboration with EWT, ensuring targeted, data-driven mitigation.

• Training and reporting: Field personnel are regularly trained on wildlife interaction protocols, leading to improved incident reporting, response and resolution. Landowners and community stakeholders are also engaged in reporting efforts.

• Innovation and research and development: Eskom has been actively involved in developing and testing new mitigation devices, including bird flight diverters customised for South African conditions, with pilot testing underway in areas such as the Karoo.

• Environmental compliance: All new powerline developments undergo environmental impact assessments guided by national biodiversity frameworks, ensuring siting away from sensitive habitats and the inclusion of bird-safe designs from inception.

“These actions highlight our commitment to the South African Biodiversity Management Plan (BMP) for vultures, where Eskom is a key partner. While challenges remain, we continue to prioritise conservation outcomes in collaboration with stakeholders. Vulture protection requires collective action.

“Beyond infrastructure interventions, threats such as illegal trade and habitat degradation also contribute significantly to vulture decline. Eskom supports continuous research to better understand these cumulative impacts and advocates for stronger policy and regulatory implementation across the board.”

Eskom said it is exploring opportunities to scale up its retrofitting programme and enhance real-time monitoring capabilities.

“Our goal is to achieve a measurable reduction in vulture mortality over the next three years, while continuing to support breeding, rescue, and education initiatives led by organisations such as VulPro as part of our commitment to achieve our vision of ‘sustainable power for a better future’ does not come at the cost of biodiversity.

“We believe that with science-led approaches, robust partnerships, and community engagement, energy and ecology can coexist sustainably,” it said.