‘Extraordinary life’: The civil disobedience campaign by ANC supporters in 1952. (AFP)

This extract from The Lost Prince of the ANC: The Life and Times of Jabulani Nobleman ‘Mzala’ Nxumalo 1955 – 1991 by Mandla J Radebe is based on the publication in July 1987 of Nxumalo’s article ‘Towards people’s war and insurrection’ in the ANC’s publication Sechaba, in which he argued that, under prevailing conditions, the ‘armed insurrection’ was possible. For him, anything less was a conservative approach that failed to read the situation correctly

The West was using the ANC’s alliance with the South African Communist Party (SACP) as a rationale for its lack of intervention, but it is precisely this reasoning that, Mzala said, demonstrated their bias. “This concern with the South African Communist Party is not genuine,” he wrote; “it is merely an artificial excuse created to avoid the responsibility of the United States, as one of the main economic supporters of South Africa, to force her to abandon her inhuman policies and practice.”

He was consistent in his thesis that the United States’ interests were informed by its narrow capitalist interests. Capitalism was another reality Mzala thought should be considered when dealing with the South African revolution.

“South African people do not only suffer from national oppression by the colonial system but are also exploited by capitalism as a system of production.”

Mzala was also urging the movement not to abandon the Freedom Charter, particularly clauses such as “All shall share in the country’s wealth”. He declared: “I foresee no circumstances that can arise in South Africa leading to the ANC abandoning this economic policy, for what will be the use of centuries of struggle and so much sacrifice if at the end people cannot control the wealth of their own country?

“A revolution without a radically democratic economic policy, detailing concrete measures for transforming the country’s economic ills and bringing to an end mass exploitation and hunger, such a revolution is not worth a single alphabet of the word ‘revolution’ ”.

These interventions by Mzala were, to an extent, a form of lobbying for a left perspective within the movement. It was through such perspectives that the interests of imperialism in South Africa were exposed. There were contending views in the ANC, expressed in the very same journal.

Eventually, in his absence, Mzala’s views were defeated. Almost three decades into democracy, the wealth distribution in South Africa still reflects apartheid patterns of ownership. Thus, Mzala’s question as to what would be the use of the struggle and sacrifice if the people cannot control the country’s wealth remains pertinent.

Mzala was still not done. In the August 1987 edition of Sechaba he continued with his scrutiny of the US with the article “People’s Power or Power-sharing? United States Policy in South Africa”. In this article, he argued: “The belief within the US state department is that interests of the South African Communist Party are served by an inflexible attitude on the part of the Pretoria regime towards negotiation with the ANC, and by the ANC’s focus on increasing military pressure on South Africa.”

To Mzala, this was a complete misunderstanding of the ANC and what it was that united its members. Thus, he asserted that the SACP could not reject negotiations in principle.

To illustrate this point, he went back to the 1962 programme of the SACP: “The party does not dismiss all prospects of non-violent transition to the democratic revolution.” However, he quickly emphasised the conditions on which the party based this principle: “[This] prospect will be enhanced by [the] development of revolutionary and militant people’s forces. The illusion that the white minority can rule forever over a disarmed majority will crumble before the reality of an armed and determined people. The possibility would be opened of a peaceful and negotiated transfer of power to the representative of the oppressed majority of the people.”

So it was that, with these articles, Mzala entered the fray on the negotiated settlement. Of course, by 1987, the genie was out of the bottle and it was apparent that a “peaceful and negotiated transfer of power” as envisaged by the SACP was increasingly becoming a likely scenario.

A month before this article was published, in July 1987, a delegation of South Africans from a broad political spectrum met the ANC in Dakar, Senegal. It was at this meeting that the “ANC for the first time in public committed itself to a negotiated settlement to end the political conflict in South Africa”.

Still, Mzala could not fathom this process outside the prism of people’s war, insisting that the position of the ANC was well known and aligned with that of the SACP. He argued: “To suggest that the ANC would, under the present circumstances, place the disarmed people on the altar of negotiations with a fascist regime is to insult the ANC and to question its sincerity and sense of responsibility to the leadership of the South African oppressed people.”

Mzala was no fool. He was not debating simply for its own sake; rather, he was addressing a perspective he felt was in danger within the ANC.

In the article, he reverted to points raised previously on the process of the transfer of power to the people. He stated that a People’s Assembly “that can set about drawing up a new Constitution for South Africa (after the draft has been thoroughly discussed by the masses in all their walks of life) can only be that which has been invested with supreme authority and power to do so, one that is vested with the sovereignty of the people”.

Although he respected the negotiations process, he was adamant that it should be about nothing else but the transfer of power from the racist minority to the democratic majority.

Mzala did not trust the imperialists’ commitments to the power transfer and therefore attached a lot of meaning to narrow concepts such as “power-sharing”. He perceived this to be an attempt by the US to engineer a deal suitable to its interests.

For him, “power-sharing” was a misguided approach to the country’s problem. “It is a concept that may appear ‘logical’ and ‘fair’ only to those who are not at all acquainted with the history of our country, and the source of our national oppression.” To his understanding, the South African struggle was following a path similar to those of other formerly colonised nations on the continent.

Mzala Nxumalo

Mzala NxumaloBecause the apartheid regime with its imperialist handlers would do anything in its power to derail the revolution, Mzala did not discount the possibility of the regime creating “a third force”. Part of the trick, argued Mzala, was for the US “to get the apartheid regime to declare its intention to hold negotiations, even long before it can be prepared to negotiate the transfer of power, and if the ANC refuses to participate, to get together puppet forces of the [Bishop Abel] Muzorewa type, and go ahead and fix a neocolonial solution for South Africa”.

In this regard, he warned the liberation forces to be vigilant against the imposition of a neocolonial solution: “Such a neocolonial solution, however, is bound to collapse even before it takes off, because the present uprising and war of liberation in South Africa is not led by those puppet forces; moreover, the people of South Africa are politically conscious enough to know who are their genuine leaders, and they equally know what they want.”

Indeed, some attempts along these lines were made, resulting inter alia in a low-intensity civil war in what are now KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. Mzala’s foresight extended to the issue of minority rights, which would be a significant issue during the negotiations. To this end, he invoked the Freedom Charter’s clause that “all national groups shall enjoy equal rights”.

Thus, he envisioned a South Africa aligned to the principles of the Freedom Charter where “all people shall enjoy equal rights whatever their colour, race or creed”. He saw no reason for the white section of the population to fear anything in a free South Africa based on the Freedom Charter, which stipulates that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white.”

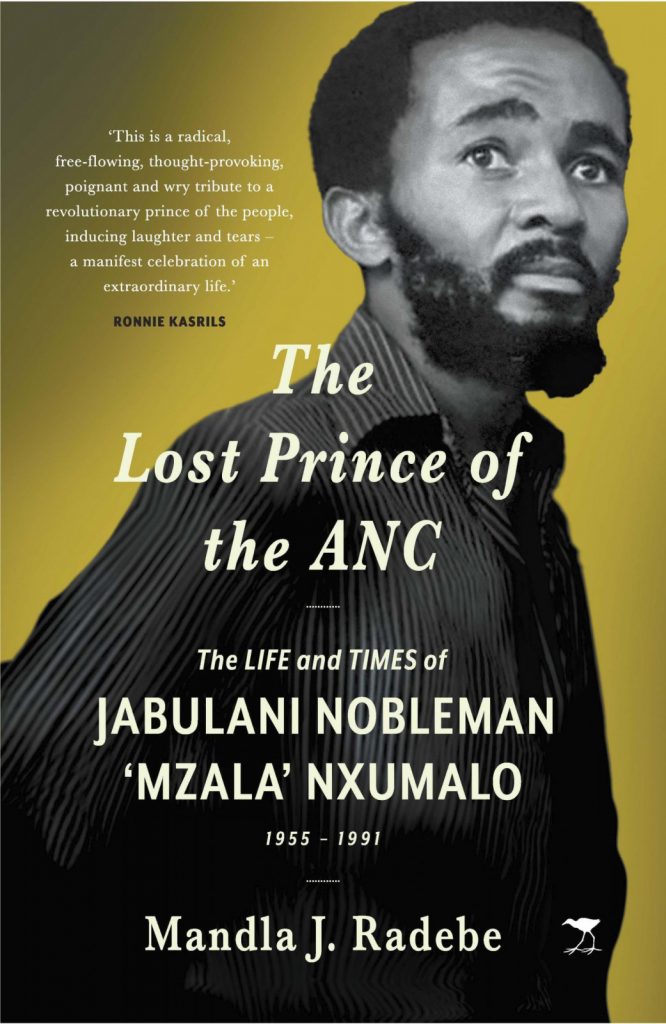

This is an edited extract from The Lost Prince of the ANC: The Life and Times of Jabulani Nobleman ‘Mzala’ Nxumalo 1955 – 1991 by Mandla JRadebe, published by Jacana Media

Mandla J Radebe is an associate professor for strategic communication and director of the Centre for Data and Digital Communications at the University of Johannesburg.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.