Poster child: A boy holds a Nelson Mandela election placard in 1994 in Lindelani, outside Durban. Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

It’s 9am, 20 December 2022. Day five of “Nasrec II” — the five-yearly national conference of the governing ANC. There is a quiet, and admittedly welcome, hush about the place.

Where is everyone?

Days one to four were packed; several thousand branch delegates from across the land. Noisy and boisterous. So, where are they now? In bed, nursing hangovers after the excitement of the early-hours outcomes of the elections for the top seven, and then “additional members”, of the all-powerful national executive committee?

But, by noon, only a few had trickled in, even though the policy commissions had begun their work. And there’s the answer — policy commissions. Policy, not power and patronage. So, the comrades had buggered off for good, done with the wheeling and dealing, and the voting.

Want to have a say in the future role of the state in a market economy or South Africa’s place in the changing geopolitical landscape? “No thanks, I’d rather skip the day and get back early for Christmas shopping; the hot cash extracted from the incentive system that tends to accompany ANC voting these days is burning a hole in my pocket.”

Mandela would be turning in his grave, or reaching from it to grab the fleeing ragamuffins by the scruff of their necks, so as to scold them for their lascivious lack of seriousness.

As a sign of the times — of the decline of the ANC as a serious political party — and as a very explicit symptom of the malaise in public life and leadership, there could be no more evocative piece of evidence.

Although it has to be said, far better to leave those policy commissions in the hands of the veteran commissars of ANC processes than the venal and vacuous and in, many cases, criminal, hands of the long-departed delegates.

Stability and no nasty or silly populist lurches. But no new ideas either. This is a governing party reaching the end of its natural political life, regardless of whether it somehow acquires the energy (and resources) to muster a strong electoral campaign next year, as it usually does.

Lastminute.com is the ANC’s middle name when it comes to such things. But the lack of talent in its leadership ranks will limit its prospects. When people ask who were the better alternatives to Paul Mashatile as the deputy president and, now, president-in-waiting, one is stumped to provide a remotely persuasive answer.

The leadership cupboard is largely bare. And there is no new generation on the rise, ready to take over from the Ramaphosa generation, let alone sustain the legacy of Mandela.

The ANC gave up on succession planning long ago; Julius Malema’s departure 10 years ago, taking most of his generation of ANC Youth League leaders with him, was the final nail in that particular coffin.

But talking of Malema, is there better leadership to be found in the opposition ranks? The red-bereted leader is a devious, faux-revolutionary populist, mostly surrounded by thugs and mindless acolytes (although away from the cameras, the EFF’s bark is far worse than its bite).

The Democratic Alliance’s John Steenhuisen was a fine chief whip during the Zuma era but his limitations are now being exposed on the national stage, where tone matters most. His double standards on Israeli transgressions of international law also reveals his lack of principle.

Those three parties took almost 90% of the votes in 2019.

The Inkatha Freedom Party’s Velenkosini Hlabisa is an old-school gent who at least brings a certain dignity to national politics.

And there is much to admire in Songezo Zibi and Rise Mzansi — a new social democratic entrant to the electoral marketplace to join the Good party in the centre-left gap that is being created by the ANC’s collapse and which must be filled if the centre-right and far-right is not to become the dominant equilibrium point for South African politics for the next generation.

Which brings us back to Mandela. He was human and flawed; and there were significant blind spots in his presidency — as Mabel Sithole and I pointed out in our book The Presidents: From Mandela to Ramphosa, Leadership in the Age of Crisis.

The pedestal on which so many choose to perch Madiba is understandable but sometimes counter-productive. On the one hand, it sets an appropriately high benchmark for future leadership. On the other, it casts a shadow so long and dark that it is hard for anyone to escape it, let alone meet the high level of expectation that it creates.

Which is why so many people reach for Siya Kolisi as a leadership model. He has a certain, one-nation Mandelian presence and charisma, reaching across all political aisles, as well as the sort of simple boys-own courage that people admire and are drawn to. He is also an excellent communicator.

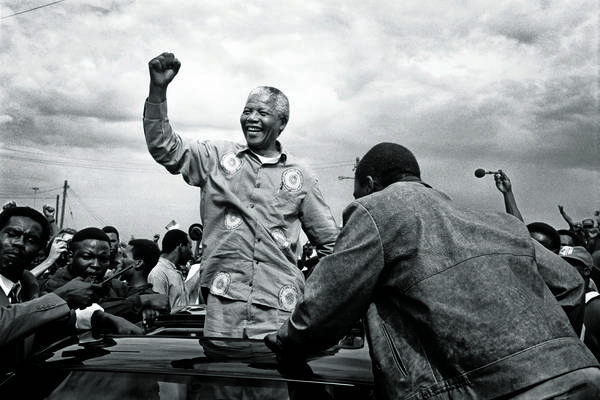

Amandla!: Nelson Mandela acknowledges supporters in Durban in 1994. Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

Amandla!: Nelson Mandela acknowledges supporters in Durban in 1994. Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

Be careful with this. Political history is littered with disastrous examples of sportsmen-turned-politicians — the Romanian tennis player Ilie Nastase springs immediately to mind. It’s rarely a good idea, although Imran Khan and Vitali Klitschko might contest this view.

And the most recent example points in the opposite direction — the former Liberian and AC Milan footballer George Weah recently failed to secure re-election as president of the West African country and conceded defeat with the same amount of grace as he showed on the playing field. Weah’s was a statement that Mandela would have been proud to make and from which Donald Trump should learn.

This points to another aspect of political leadership that is sorely lacking in South Africa at present — humility. Although Mandela could be mighty imperious at times, he was not scared of being held to account.

Famously, when Louis Luyt sued him in 1996 over Mandela’s appointment of a commission of inquiry into rugby — from which, by the way, one might trace rugby’s relatively successful transformation — he not only acceded to giving evidence in court, standing for several hours while both counsel and judge sought to humiliate the new president, but accepted the loss in court.

Mandela literally, as well as figuratively, stood up for the rule of law. Now, politicians across the board duck and dive to avoid accountability; there is a shamelessness to the sense of impunity that is causing great harm.

Former president Jacob Zuma has a lot to answer for in this respect but the way in which the modern ANC is unable to cope with the consequences of the Zondo commission’s findings against 100 party leaders is symptomatic of the ethical decline of the party of democratic liberation.

Mandela would not have tolerated it. Nor would he have tolerated the predatory nationalists within the party, who were given a licence to plunder by Zuma and against whom President Cyril Ramaphosa appears unable or unwilling to take a strong enough stand. Brazenly, they resort to lawfare or hide behind their provincial power bases.

Like OR Tambo and Albert Luthuli before him, and to a lesser extent Thabo Mbeki after him, Mandela’s greatest trick was to manage the complexity of the ANC, principally by pulling its nationalist and socialist wings towards the middle, thus enabling the party to “lead society”, in its fabled phrase, by being a large sponge at the centre, soaking up all manner of socio-economic pressures.

When Mandela left, he not only left his long shadow, but a huge political vacuum into which a long cast of scoundrels and political opportunists have jumped, causing untold havoc to South Africa’s body politic and socio-economic stability. In a negative sense, this is Mandela’s bequest.

More positively, the country has lost a beacon of hope and a statesman of stature. Taiwan was an uncomfortable blemish on his record as president, although an understandable one given the impossibility of sustaining a two-Chinas policy.

Mandela always sought to apply an equal standard in relation to the application of international law. He was taken seriously at both home and abroad.

His stature and credibility lent stature and credibility to South Africa and its government. Who would not have wanted to serve his presidency? Nowadays most talented young South Africans want to work in the private sector and who can blame them? Democratic consent is undermined and the constitutional order weakened. Mandela would not have been pleased. The finger would have wagged.

Today’s generation of political leaders is falling far short. It is time for someone to step up and reverse the trend.