South Africa's hosting of the G20 is an opportunity to represent Africa's interests. Photo: Aditya Pradana Putra/Antara/ Pool/Handout/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

In 2025, South Africa will become the first African country to assume the presidency of the G20, taking over from Brazil. In the midst of a global polycrisis, South Africa’s G20 presidency offers an opportunity to reshape global governance on three critical issues: global financial reform, climate action and a just energy transition, and sustainable food systems.

Thirty years ago, G7 countries constituted nearly 70% of the global economy. In contrast, by 2024, the Brics+ bloc accounted for about 35% of the world’s GDP, compared with the 30% held by G7 countries. Meanwhile, G20 countries currently represent 85% of the global economy, 75% of global trade and 63% of the world’s population. This shift underscores the growing influence and significance of emerging economies.

South Africa’s membership in the G20 and Brics+ stresses the country’s role as an economic and political powerhouse both on the African continent and increasingly in the Global South.

Can South Africa’s G20 presidency be an opportunity to reshape global governance at a moment of heightened geopolitical tensions and a fragmented international system characterised by multiple and simultaneous crises, including the climate and energy crisis, the Russian-Ukraine conflict, and Israel’s war on Gaza?

Founded in 1999 in response to the global financial crisis, G20 is the main forum for international cooperation and plays an important role in defining and strengthening global architecture and governance.

Why global financial reform is urgent

With many developing countries burdened by growing debt, the need to reform the global financial architecture has never been more urgent. More than 3.3 billion people live in countries that spend more on debt servicing than health, education and social protection. According to the United Nations Trade and Development Agency, African countries’ debt has increased by 183% since 2010 — four times higher than its economic growth rate over the same period. As global borrowing shifts towards private creditors, many developing countries are finding it increasingly difficult to finance development.

The reasons can be varied and context specific but three stand out: first, the complexity of the creditor base makes debt relief and restructuring extremely difficult because it requires negotiating with a wider range of creditors, sometimes with diverging interests and legal frameworks. Delays and uncertainties in debt restructuring increases the cost of resolving debt crises.

Second, lending by private creditors is volatile and prone to rapid shifts especially during crises when investors pull back to safety. This can lead to resource outflows when poor countries least afford them. For example, in 2020, developing countries paid $49 billion more to their external creditors than they received in disbursements, resulting in a negative net resource transfer.

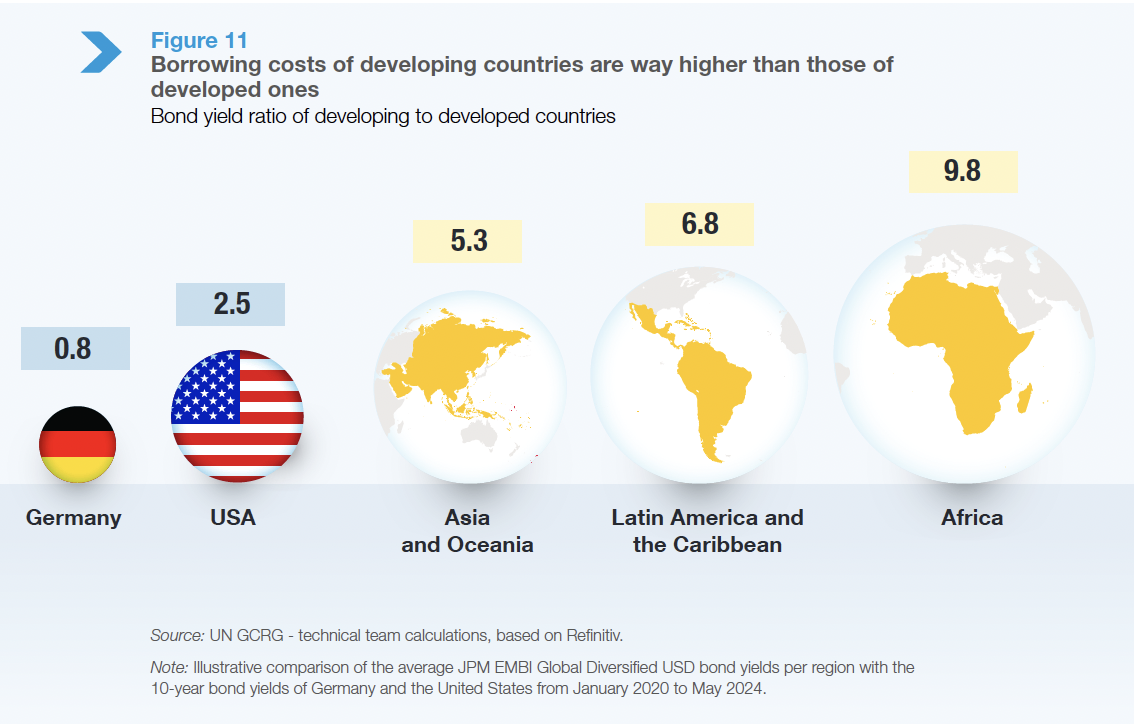

Third, borrowing from private sources on commercial terms is more expensive than concessional financing from multilateral and bilateral sources. The inequalities embedded in the international financial architecture exacerbate differences in the cost of financing. For instance, borrowing costs for developing countries range from two to 12 times higher than those of developed countries, making it difficult for developing countries to access and finance development.

In 2023, 54 countries allocated 10% or more of government revenue to interest payments. Designed as an economic rescue package for postwar Europe, the current global financial architecture is not only dysfunctional but unfit for purpose in a world characterised by complex, multilayered and interconnected crises, including climate change. As a major Global South player, South Africa can leverage its membership in the African Union, G20, Brics+ and other fora to rally support for global financial reform and advance concrete policy proposals for a responsive and inclusive global financial architecture fit for the 21st century.

Figure 1: Borrowing costs for developing countries are higher than those of developed ones.

Figure 1: Borrowing costs for developing countries are higher than those of developed ones.

South Africa’s presidency will coincide with the fourth International Conference on Financing for Development set for mid-2025 in Spain, which brings together heads of state, G20, the United Nations Economic and Social Council, the UN secretary general, and heads of international financial institutions. This can be an opportunity to advance policy proposals to achieve progress in building a stronger and fairer international financial system.

Climate change and a just renewable transition

While the urgency of addressing climate change and advancing a just energy transition is crucial, for Africa and the broader developing world the priority must be ensuring energy access for the 750 million people who still lack electricity. Providing affordable, clean and reliable energy is not only essential for climate mitigation and adaptation but also presents an opportunity to catalyse investments in the green economy. As South Africa assumes the G20 presidency and continues to be a leading voice for the Africa Group in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, it must champion this perspective.

Additionally, South Africa must play a pivotal role in translating Africa’s increased representation at UN Conference of Parties meetings into tangible outcomes, using existing frameworks and instruments to hold the Global North accountable to its commitments to the Global South.

Building global consensus on climate change and a just energy transition hinges on two priorities. First, the shift towards renewable energy must be sustainable and equitable, ensuring that all countries benefit from cleaner technologies. Second, climate change adaptation strategies must be developed and implemented, with robust finance and security packages for vulnerable countries.

Transforming Africa’s food systems

Despite the current global food systems’ capacity to produce enough food for everyone, more than 800 million people experience hunger daily, and about two billion are food insecure. In Africa, this situation is exacerbated by natural disasters, wars, fragile global supply chains and economic inequality, which underscore the vulnerabilities of a globalised food system. These interconnected systems mean that shocks in one part of the world can rapidly spread, often with devastating effects on lives and livelihoods.

The UN Food Systems Summit in 2021 aimed to address three interrelated global problems: an increase in undernutrition and overnutrition, the unsustainable food production methods contributing to climate change and environmental degradation, and social inequities within food systems.

Unsustainable food production systems are central to global vulnerability to climate change and growing food insecurity. For instance, food production accounts for 26% of global greenhouse gas emissions, half of the world’s habitable land and 70% of global freshwater withdrawals. The Food and Land Use Coalition estimates costs related to unsustainable food systems at about $12 trillion — nearly four times more than the market value of the food system itself, which was estimated to be $3.6 trillion in 2021.

Placing these three interrelated issues at the centre of South Africa’s presidency of the G20 will provide space for innovative policymaking to tackle these complex problems. By reforming the global financial architecture for example, developing countries can access finance which is key to unlocking renewable energy potential — itself a source of climate mitigation and adaptation. Addressing these global issues could help unleash Africa’s agriculture and food systems potential.

With Africa’s population expected to double by 2050, ensuring that people have access to clean, affordable and reliable energy, and healthy and nutritious food delivered in affordable and sustainable ways is key to accelerating progress towards the sustainable development goals and Agenda 2063. Evidence including from the European Union’s Farm-to-Fork strategy shows that well-designed and properly financed agriculture programmes can help correct underlying food system failures by linking eradication of hunger to wider public health, environmental, energy and climate goals.

Darlington Tshuma is a research fellow at the Istituto Affari Internazionale’s Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa Programme and a postdoctoral researcher at the Thabo Mbeki African School of Public and International Affairs, Unisa. Bongiwe Ngcobo is a research associate at the Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation at the University of Johannesburg.