Reviled: Fethullah Gülen lived in exile in the United States after he was accused by Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of plotting a coup. (Thomas Urbain/AFP)

“Be so tolerant that your bosom becomes wide like the ocean. Become inspired with faith and love of human beings. Let there be no troubled souls to whom you do not offer a hand and about whom you remain unconcerned.” — Fethullah Gülen

Muhammed Fethullah Gülen (born in 1941) was an Islamic scholar, preacher and social advocate with a decades-long commitment to education, altruistic service and interfaith harmony. He was the leader of the Hizmet (service) Movement, making him one of the most influential Muslim leaders in the world, and he died in exile in the United States on 20 October 2024.

Reviled and revered, depending on the speaker, Gülen and his movement have left an indelible mark on Turkey, the Turkish diaspora and, equally significant, the educational and social services in many countries, including South Africa.

The trajectory of his remarkable life, writings and work is easy to follow. Yet, most of what is written about him online is couched in simplistic, sloppy terms, revealing both the shallowness of social media and its power in creating and controlling narratives. Unexamined terms, such as “Islamist”, “terrorist” and “cultist”, are bandied about, amplified by the loudest vuvuzelas, all funded by a powerful regime that he dared to cross.

At the earliest stage of Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s reign, Gülen regarded his political manifesto as a useful channel for advancing his movement’s ideas and values. Once in power, these manifestoes and slogans quickly withered, and so Gülen’s criticism of Erdogan increased.

Erdogan’s rapid morphing into a 21st century absolutist sultan with plans for a 1000-roomed palace — which Gülen denounced as prohibited by Islam and which Erdogan completed — and his removal of prosecutors investigating allegations of his family’s financial corruption were but some of the things that provoked Gülen’s ire. Erdogan had to deal with an ancient challenge faced by numerous dictatorial sultans before: “Who will save me from this pesky cleric who had grown too big for his boots?”

The perfect opportunity came in 2016 with an attempted “coup”. (Among academic scholars, the jury is still out on whether this was a genuine coup or a planned sideshow by Erdogan to rally support.) Gülen and the movement he led were held responsible.

Erdogan’s purge of all who identified with the Hizmet Movement’s ideas and who had been a bone in his the president’s throat was swift. Academics, journalists, civil servants and judges were not spared. Seizing property, incarceration, illegal renditions of those in exile, torture — all the usual weapons available to dictators were hauled out.

Despite Gülen condemning the “coup”, the regime’s propaganda machinery went full speed, employing old and new tropes to controversialise Gülen and the Hizmet Movement. He became the “devil incarnate”, “Islamist-fundamentalist”, “cultist”, “a cancer” and “a cockroach”.

With his demise, anyone in Turkey uttering the standard Muslim phrase upon receiving news of a death (“Indeed from God we come and unto God we return”) is thrown into jail. It’s a bit like talking about Palestinians as human beings in Israel.

“It becomes publicly and legally impossible to have a candid conversation about it [the Hizmet Movement]. Anything short of passionate condemnation of it can be tantamount to treason itself.”

Gülen was an advocate for Islam’s presence in the public sphere, arguing that this was crucial to the formation of an ideal society. Did that make him an “Islamist”?

This was his vantage point, a Turk and Muslim by birth and passion. But he consistently argued for an approach to Islam independent from the state.

“The duty of the state cannot be raising a religious generation. […] This will mean imposing a certain opinion on those who think differently.” He advocated for all religious traditions, especially the Abrahamic ones, to have this public presence and opposed the Muslimification of historic Christian churches in Turkey.

Gülen’s well-documented written works and speeches testify to a person deeply moved by his faith, simplicity, moral values, calls to justice and the spiritual underpinnings he desired as lodestars for Turkish society. (He led an austere life, leaving no property or wealth behind.) These values were articulated in personal ways, unaccompanied by a more extensive critique of the systemic economic forces that pour billions of dollars into entrenching injustice. The social concretisation of these values did, however, lead him to support the political tendencies of parties such as Erdogan’s AK Party, whose manifestoes showed the best promise for his ideals.

Did this make him a formal political ally of Recep Erdogan?

Not once did Gülen suggest that he was interested in political power. He rejected what he regarded as the politicisation of religion. All the education institutions founded by the Hizmet Movement aimed to produce quality, well-rounded scholars in all fields, including education, science, Islamic and contemporary law.

The graduates were encouraged to enhance the movement’s values in their chosen professions and inculcate the values of service and justice. But, in a political system where the only value that matters is jumping at the finger-click of the sultan, promoting these values is regarded as treason. (South Africans remember the days when workers scraping “ANC” on their metal coffee mugs were sentenced to a minimum of five years for terrorism.)

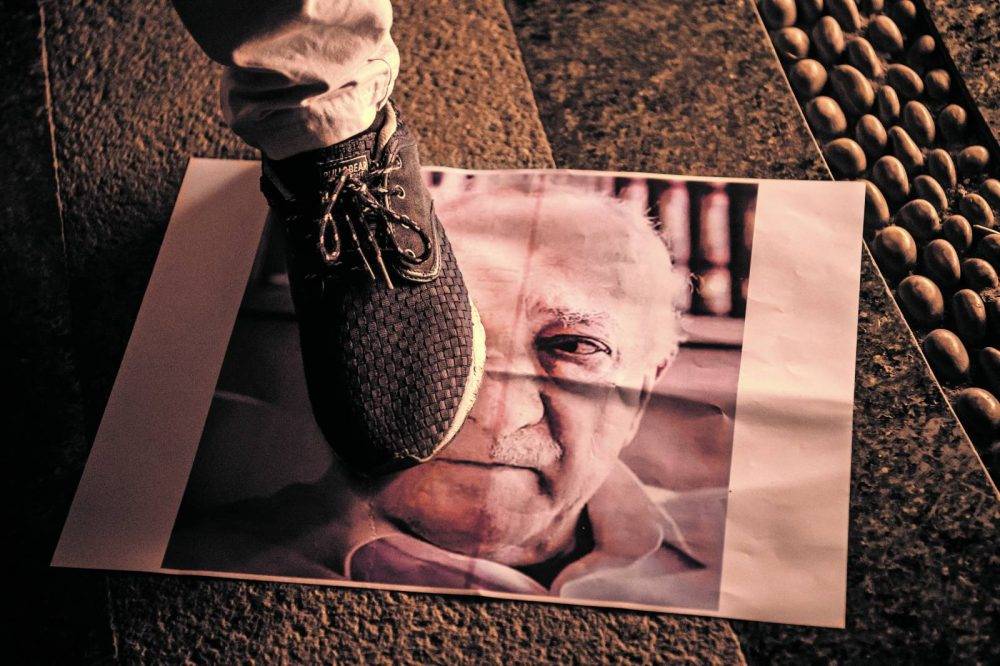

A pro-Erdoğan supporter walks on a poster of Gülen during a rally in Istanbul in 2016 after the alleged “coup attempt”. (Ozan Kose/AFP)

A pro-Erdoğan supporter walks on a poster of Gülen during a rally in Istanbul in 2016 after the alleged “coup attempt”. (Ozan Kose/AFP)

Is the Hizmet Movement a cult?

I have closely observed the Hizmet movement in the US, Europe and South Africa for more than two decades. As a scholar of religion, I can smell a cult a mile away.

Some of the commonly agreed upon characteristics of cults are a) isolating its members from their families and larger societies, b) the rejection of all non-followers as “fallen” or destined for hell, c) zero tolerance for criticism or questions and d) the “taxation” of members for undisclosed causes — usually for the enrichment of a leader.

Wherever the Hizmet Movement has planted its seeds, its work has been characterised by serious attempts to engage — not proselytise — people of various communities. Notions of winning over “other Muslims” or non-Muslims are absent from its programmes. Its frequent inter-faith dialogue events are just that — to promote understanding between faiths and to advance the values that drive them.

Cults invariably produce many disillusioned defectors who write about their experiences on the inside and expose the nasty underbelly. I have not encountered any in my years of studying the movement. The movement does have internal formation programmes for its members, and all serious scholars are welcome to probe them. Quite simply, all its teachings are transparent.

Every single project of the movement — largely self-funded and ranging from building mosques to establishing health centres, cultural foundations, a large network of welfare work and feeding schemes — is directed at the larger community.

As in 160 countries, Gülen’s vision inspired the global Hizmet Movement in South Africa. This movement has established schools producing the finest matric results in the country, charitable organisations and platforms for interfaith dialogue mainly focusing on promoting science, literacy and community service. The movement has a significant and deeply impressive footprint and is run by full-time volunteers and staff on a small budget.

Most moving is watching these volunteers set aside their pain as they go about the daily basis of their calling: living and acting in service of humanity in general and, more specifically, South African society.

Farid Esack is professor emeritus in the department of religion studies at the University of Johannesburg.