The air force’s

Oryx and Rooivalk helicopters, which are manufactured

by Denel. File photo by Born/Gallo Images/The Times &

Sebabatso Mosamo/Sunday Times

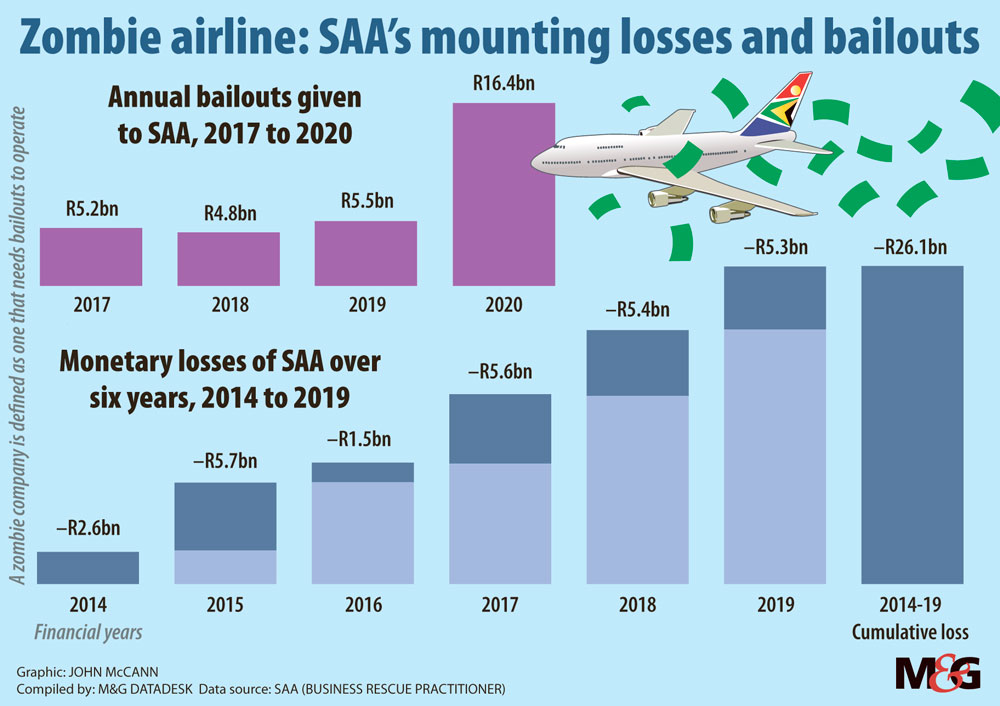

With about two weeks to go before the medium term budget policy speech, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni — otherwise known as Twitter’s Glenryck Pilchards’ chief influencer — is probably sitting on the worst kept secret: the government will once again issue a cash bailout for SAA.

Although there is nothing fundamentally wrong with giving a bailout to a state-owned entity, SAA has shown time and time again to be a bad investment.

And the allocation will come at a time when the country is being urged to stop expenditure that will not contribute directly to the cause of reviving our Covid-ravaged economy.

The ‘vanity project’

Even commercial banks — who are known to easily throw money at state-owned enterprises as long as a government guarantee is in place — are said to have baulked at recent requests by the treasury to provide the R10-billion needed to make way for a new SAA.

The narrative Public Enterprises director general, Kgathatso Tlhakudi, would have us focus on is the value the airline has to the economy. SAA, through its R24-billion procurement spend, is an important player in South Africa’s aviation sector, which contributes 70 000 direct jobs and a further 360 000 jobs through the supply chain and tourism.

But critics of this plan argue that any gap left by SAA will be filled by new or existing airlines because the demand for air travel will still be there.

Some argue that any interest to partner with SAA now is driven by other factors such as South Africa’s positioning and infrastructure as a hub in this part of the world, and the advantage one could have to operate a maintenance and repair organisation such as SAA Technical.

Critics have also said that continuing to throw money at SAA, which had been given more than R50-billion bailouts in the past 21 years, is tantamount to subsidising elite travel in a country with a more urgent need for basic rights such as clean running water, a reliable energy supply and adequate healthcare.

While Mboweni will no doubt once again read the riot act to SAA as he delivers the cash injection, he will be silent on another proudly South African state-owned entity that has hit dire straits — Denel.

Missing out on big deals

Like SAA, Denel can attribute the bulk of its problems — the heights of which saw it ask employees to bring their own toilet paper to work — to corruption and poor leadership.

Although its story is not as well known as that of Transnet, Eskom, and SAA, Denel was close to the heart of state capture. With hundreds of millions of dollars in annual revenue from international contracts, the state’s defence equipment and technology company was a meaty carcass for state capture vultures.

The Special Investigating Unit is looking into allegations that intellectual property, including Denel’s world-leading missile technology, was stolen and handed to the Saudi Arabian Military Industries (Sami), one of the many entities interested in buying a stake in Denel.

Denel’s value is in the sovereign capability it gives South Africa, as well as its revenue potential. Sovereign capability is a country’s ability to design, maintain, sustain, enhance and develop its defence assets.

Thanks to Denel, South Africa is one of a handful of nations to have fielded a functional and operational anti-missile defence system, and its varied air to air and surface to air missile offerings, which are sold to clients all over the world, make it a world leader in guided weapons.

In mid-2019 Denel’s former group chief executive officer, Danie du Toit, said they anticipated R30-billion revenue from contracts in the next two years, and this was expected to change the entity’s financial misfortunes. As a result of this, the government pumped R1.8-billion into Denel in August last year, despite the company recording a R1.76-billion loss in 2018.

A year later Du Toit, frustrated by lack of proper capitalisation and the feeling the pressure of the Covid-19 lockdown, would resign from Denel. An amount of R576-million allocated to Denel by Mboweni in this year’s budget was ringfenced to reduce the state-owned entity’s government-guaranteed debt. Denel has now asked that R271-million of this be released to fund operations.

Danie du Toit.

Danie du Toit.

In this time Denel has missed out on R25-billion worth of work in Oman, India and Egypt — the latter being a R4.5-billion contract to supply 96 navy surface to air missiles that was lost because Denel could not produce a R15-billion guarantee.

The treasury is aware of how precarious Denel’s situation is — it recently told parliament the company was a serious candidate for business rescue.

But no one, from Denel’s leadership at executive and board level to government, seems to be working with the requisite speed to avoid a repeat of the shambolic SAA business rescue process.

What makes this situation border on criminal negligence is that, unlike SAA, Denel and its subsidiaries is a cash cow, and this is evident in the number of companies that have expressed interest in either taking equity in Denel or partnering with it on available contracts.

Options to save Denel

Since last year Denel Aeronautics has been courted by Airbus Helicopter — the French company has supplied its platform and powertrain for the Oryx and Rooivalk helicopters respectively — United Arab Emirates-based Transworld Aviation and SanDock Austral, a black-owned South African engineering company.

Denel Dynamics — the missile producer — has caught the eye of Germany’s Rheinmetall and Sami, while Denel Land System has received expressions of interest from South Africa’s arms manufacturer Truvelo, the dubious company Southern Palace, Sami and controversy-hit Paramount Group.

Last week Denel’s acting chief executive, Talib Sadik, said the company was continuing with its strategy of “improving operational performance, divestment of non-core businesses and securing strategic equity partners as part of its plan to stabilise and grow Denel”.

“We have received a number of unsolicited offers for partnerships or equity from local and international players in the defence and technology sectors. We are in the exploratory stages of this process and we will follow all the relevant legislative requirements and a governance process with the shareholder as we pursue opportunities and consider the range of options that are available to Denel.

“Denel is certain that the strategic equity partnerships will bring in the sustainable market access, necessary capital injections, technology and further strengthen its relationship with the SANDF [South African National Defence Force] by maintaining important and sovereign capability within their declining budget environment,” he said.

Sadik’s language suggests doing away with government handouts and rekindling the relationship with the defence department. The two are discussing a retainer from the department to Denel in return for maintaining sovereign capability.

Good idea, were it not for the fact that Armscor — the department’s procurement arm — and the new secretary of defence, Gladys Kudjoe, bemoaning lack of funds to modernise the SANDF’s equipment.

Armscor recently told parliament that the drying up of funds was compromising projects including Biro (inshore patrol vessels for the navy), Hotel (a new hydrographic survey ship), and Hoefyster (a new generation combat vehicle for the army).

Holding the purse strings

The treasury and the public enterprises department have said they have not been formally appraised by Denel of any approaches by other companies, which gives rise to the question: does Denel’s leadership fully understand the position it is in?

Last week the treasury said it “remains supportive of reforms including partnering with the private sector by state-owned companies with the intention of reducing its reliance on the fiscus for financial support”.

In real terms though, Denel’s predicament provides a stark reminder of the fact that SAA did not happen in a split second. It has taken years of mismanagement, corruption and indecisiveness hidden behind carefully crafted words.

A lacklustre approach is hardly what is needed given that state-owned enterprises have about R385-billion in government-guaranteed debt and are an integral part of the post-Covid economy.

Or perhaps the intention is that this time next year Mboweni will be getting ready to announce the government’s “decisive” intervention at Denel.

[/membership]