Even before the first Covid-19 case was confirmed in South Africa, SAA was in as bad shape as it gets (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

NEWS ANALYSIS

The Covid-19 pandemic is fatal for people with compromised immune systems. The same can be said of companies with weak balance sheets.

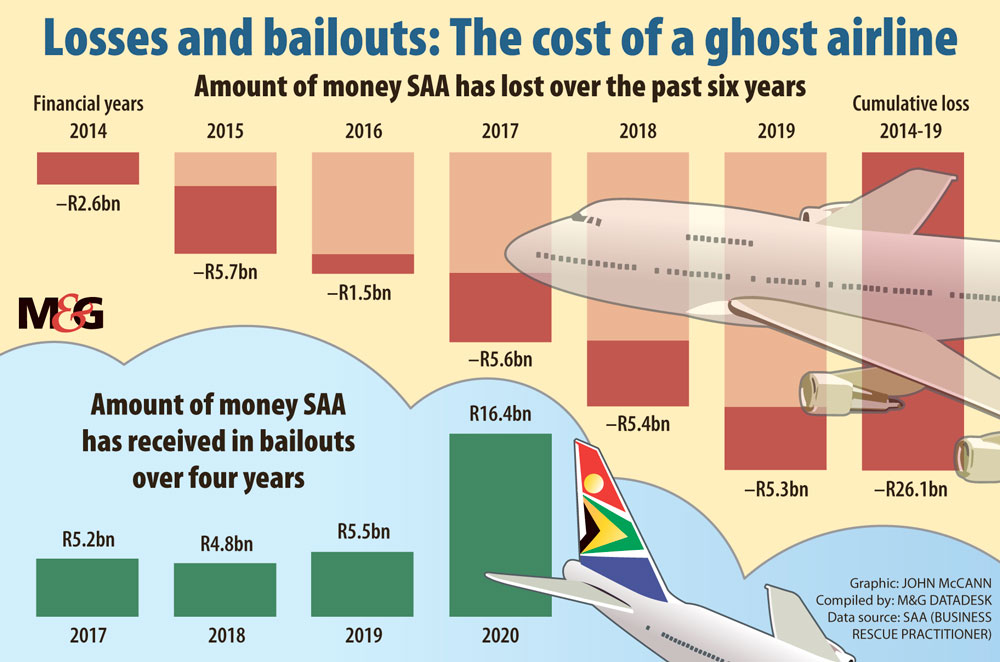

After more than a decade of being hamstrung by politically driven decision-making that sabotaged any business sensibilities, business rescue was supposed to be a ventilator of sort — a lifeline for South Africa’s state-owned airline. Between 2014 and 2019 it ran up losses of R26-billion.

Long before the first Covid-19 case was confirmed in South Africa, SAA was in as bad shape as it gets. But now, with the coronavirus cutting a swathe through the world’s economy, the airline’s landing strip seems to have finally run out.

What we know about any attempt to manage the more deadly symptoms presented by Covid-19 patients is that getting them onto a ventilator quickly makes a big difference. Similarly, the economic effect of the virus on the aviation sector worldwide requires an ability to act fast and be innovative in the approach to crises.

This kind of decisiveness — and willingness to embrace change — is something SAA might need and something the government has not displayed when dealing with the airline.

This week’s decision to defer discussions about SAA to another meeting later this month, after Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan has presented his report on SAA, is a missed opportunity by the government to show its ability to move fast on important issues.

But this is nothing new. It is typical of how the government has dealt with the airline in the past — and more recently, when it was put under business rescue.

SAA is out of time. It has been out of time since December, when business rescue kicked in. But the government has been hesitant to provide the intervention needed to bring SAA back to life with a R5.5-billion cash injection.

Costs of liquidation

One of the reasons the airline’s business rescue practitioners, Les Matuson and Siviwe Dongwana, have not applied to change the business rescue attempt to liquidation is it would leave most of the SAA group’s 8000 employees in a worse position than if some are retrenched.

Retrenchment and restructuring would have seen subsidiaries such as SAA Technical, SAA Cargo and Air Chefs sold off, and about 2268 of the 4708 employees at SAA itself being retrenched. This is according to a warning sent to unions late last month.

A liquidation application would make SAA the second state-owned airline to throw in the towel. SA Express did so recently, when the Covid-19 pandemic took off.

Critics of the lack of decision by Cabinet include Democratic Alliance MP Alf Lees has criticised the Cabinet’s indecision. He has called Matuson and Dongwana to initiate the liquidation process.

“The R50-billion bailouts to SAA since 2009 have come at a great loss to the taxpayer and the country, as South Africans had to endure cuts to essential public services to subsidise a failing airline,” Lees said.

“As the Covid-19 lockdown continues to wreak havoc on the economy, the money spent on SAA and SA Express could have been useful in helping the government absorb the economic shock. As things stand, the government is broke and has no fiscal space to pursue a wider economic bailout intervention.”

Lees, who has also called for an urgent virtual sitting of Parliament’s standing committee on public accounts and for President Cyril Ramaphosa to institute a commission of inquiry into SAA going back to 2009, added that the liquidation of SAA and SA Express should take place in a manner that protects the country’s economy and employees.

Matuson and Dongwana’s spokesperson, Louise Brugman, said the two regard business rescue as ongoing and are working hard on consultations with labour unions, as required by the Labour Relations Act’s section 189, which sets out the process for retrenchments.

State refuses more debt

Speculation has been rife that liquidation is likely after Matuson and Dongwana informed parties affected by SAA’s business rescue that Gordhan — SAA’s government shareholder representative — had this week declined a request for a R10-billion bailout to assist the airline to deal with the headwinds created by Covid-19 and to finalise its restructuring.

That speculation looks increasingly justified; it has only been three weeks since business rescue practitioners at SA Express filed a court application for liquidation — a move that is being opposed by Gordhan.

Phahlani Mkhombo and Daniel Terblanche’s application came after SA Express’s financial situation, became so dire that salaries were no longer guaranteed, and any sort of funding requests were being ignored by the shareholder.

The decision to not give SAA R10-billion means the airline is yet again on the brink of collapse. It can’t raise more money from overseas, with Gordhan also declining its request for an extension of foreign borrowing limits.

The business rescue practitioner’s request for more money is on top of the R5.5-billion, from private lenders and the Development Bank of Southern Africa, in post business rescue commencement funding received at the start of the business rescue process.

State knew it had to spend

Critically though, as practitioners Matuson and Dongwana indicated to affected parties this week, government — in choosing to restructure SAA — has always been aware that a further R7.7-billion was required to fund repayments to creditors, restructuring costs, retrenchment costs and to recapitalise SAA’s subsidiaries.

Their understanding was that this would be announced by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni during his budget speech in February and thus allow them to publish their business rescue plan within the required 90 days.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

But Mboweni, who has always been clear that he prefers the state to shed itself of the SAA albatross, instead appropriated to SAA and SA Express just enough money to cover the government guaranteed debt. In the case of SAA this included this year’s R5.5-billion advanced by lending institutions.

“This is what surprises us the most,” said a senior SAA insider about the decision not to provide the R10-billion, which was communicated by the government on Good Friday. “But it is what SAA is. We take one step forward, and then a couple more back. This time it’s harder to accept because very little else can be done.”

It was also known to the government that speed was key as evidenced by Matuson and Dongwana’s communication to labour unions at SAA that the retrenchment consultation process would need to be concluded by the end of April — in half the time usually set aside for this process — to accommodate available funding.

SAA workers on strike (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

SAA workers on strike (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

But that was before the Covid-19 travel restrictions, which have affected the aviation sector and has seen bigger and stronger economies in Europe and the Middle East, as well as the United States, discuss or commit to billions of dollars in bailout funding — in some instances for airlines that are not even state-owned. Airlines have also requested industry concurrence that cancellations necessitated by the travel restrictions be exempt from refunds, to cushion them.

In an attempt to keep flying and generate some income, SAA has operated commercial flights to evacuate foreigners and repatriate citizens stuck in other countries, and also ramped up its cargo operations, repurposing some of its passenger aircraft to transport food, medical supplies and vehicle components.

During the lockdown period, SAA spokesperson Tlali Tlali said the airline has moved a little over 4000 people and 204552kg of cargo. These numbers, though miniscule, provide a glimmer of hope for the airline.

Political meddling

Covid-19 implications aside, the SAA business rescue saga has been anything but smooth, and the same political meddling and indecisiveness that saw the airline land here in the first place continues to hamper progress.

In the five months of business rescue, the government has failed twice to live up to its end of the bargain — first in February when R2-billion promised as part of business rescue post commencement funding did not materialise and saw SAA cancel flights to save money, and again when no announcement was made about further required funding.

Rescue as an option only came about because the airline’s board — then led by SAA’s acting chairperson Thandeka Mgoduso and turnaround custodian Martin Kingston — could no longer bear the pressure of being at the helm of an airline that was trading recklessly, and were facing several threats of liquidation applications.

The only way lenders — in the form of commercial banks led by Nedbank — would advance funding for SAA’s business rescue was only if Matuson was appointed practitioner for the biggest business rescue in the country’s history.

Although the government initially agreed to this, it could not truly let go and within a week of Matuson’s appointment he was joined by the former public works director general, Dongwana.

The question of whether the government would truly be able to let go would soon be answered — within eight weeks of taking over the reigns Matuson and Dongwana issued a statement that SAA would cut all domestic routes except between Johannesburg and Cape Town in effort to address costs.

This was met with nothing short of outrage at the highest levels of government, and saw Ramaphosa himself issue a statement that the government was not convinced of this decision and would meet the business rescue practitioners and for them to make representations.

The accusations of government lip service aren’t new: several senior SAA insiders are now arguing that the government always knew the restructuring option they chose would have required funding. Covid-19 only accelerated a request that would have inevitably landed at the public enterprise department’s desk.

The Zuma-Myeni years

Much of the recent damage to SAA dates back to the appointment of Dudu Myeni as chairperson of the airline. The former chairperson and corruption-accused was known for her close relationship with former president Jacob Zuma. It was this relationship that saw Myeni receive political cover from Zuma.

Myeni, a school teacher who arguably should never have been allowed to serve on a school governing body let alone the board of an airline, was able to derail numerous opportunities to transform the airline’s trajectory — for her personal gain.

Case studies that easily come to mind include scuppering a codeshare deal with Emirates Airways that would have added R2-billion to SAA’s revenue and seen it make a profit in 2015, and meddling in a proposed aircraft swap deal with manufacturer Airbus that saw the treasury warn SAA that it was threatening the fiscus. Myeni is also accused of attempting to insert people linked to her into a R15-billion debt consolidation transaction that would have earned them R256-million.

Grounded: The relationship between former president Jacob Zuma and Dudu Myeni contributed to the airline’s demise. (Kevin Sutherland/The Times)

Grounded: The relationship between former president Jacob Zuma and Dudu Myeni contributed to the airline’s demise. (Kevin Sutherland/The Times)

SAA under Myeni’s leadership entered into a codeshare deal with Etihad Airways that saw it lose R100-million in a month. The deal, which was signed despite forecasts saying it would lose the airline up to R70-million in the first year, was subject to investigations by the treasury and the auditor general.

From late 2012, when Myeni was appointed chairperson of SAA, to 2017, when she left, the airline had six chief executive officers and paid for several turnaround strategies —most of which indicated that staff reduction was critical — without a single one being fully implemented.

The airline also nearly lost its licence to operate in Singapore after failing to submit audited financial statements for two consecutive years.

In what should serve as an indictment to the current political leadership overseeing SAA, the airline went into business rescue having last submitted financials to Parliament in 2017.

Lessons not learned

What this period shows is that lessons from the Zuma and Myeni era, about political interference in operations and placing political considerations over the needs of the airline have not been learnt.

If it was not so, SAA’s last chief executive, Vuyani Jarana, would not have quit the airline, citing shareholder interference and lack of support for his endeavours to save SAA as reasons for his leaving.

Jarana’s frustrations were with the government not coming to the party in terms of funding, despite accepting his turnaround plan and knowing the financial costs of this.

In the government’s defence it is hard — and even political suicide right now — to give SAA the money it needs to turn the airline around, without affecting more urgent needs in the economy (exacerbated by Covid-19) and attracting public outrage.

But the shareholder then fails is to be honest with the public and SAA about what is possible and what is not. Organisational strategy consultant Thabang Motsohi, who has decades of experience in aviation and consulted at SAA in Jarana’s office, said business rescue was bound to fail because of the same issues that led Jarana to leave the airline: meddling and no real commitment from the state.

Motsohi, whose aviation experience includes a stint at the successful Ethiopian Airlines, said much of the government’s bizarre handling of SAA can be blamed on an overall lack of strategy when it comes to state-owned businesses.

“One of the questions nobody in the ANC or in government can answer is what is the purpose of having SAA. Do we want an airline that will operate on a commercial or developmental basis?

“When the president, who won at Nasrec by a narrow margin, speaks to alliance partners about the need to run an efficient and commercially competitive airline with optimum employee compliment, he is met with responses of being against the developmental agenda, and the discussion stops there. It’s a sad state of affairs.”