The Vygies are members of any of the species of Mesembryanthemacae family, a succulent groundcover plants, native and common in southern Africa.

Marcus Byrne is old enough to remember how scores of nocturnal insects used to splatter on his windshield.

Now, decades later, there’s far fewer dead bugs. “And that’s pretty worrying to me,” says the professor of entomology and zoology at Wits University.

It’s been described as a snowstorm of moths and that’s how Byrne remembers it too.

“Driving at night required skill and the tenacity, despite the temptation, to not switch on the windscreen wipers, which would then smear the moth blotches into a greasy mess,” entirely obliterating the view of the road.

In recent years, scientists have coined the term the “windshield effect” to describe insects’ disappearance.

Byrne says there’s now good scientific evidence to show that insect numbers are in decline. “We also have very powerful anecdotal evidence from citizen scientists – you and me – that insects are in decline.”

For him, the most dramatic anecdotal evidence is the disappearance of the swarms of nocturnal insects that used to be attracted to lights at night – headlights, porch lights or brightly lit petrol station forecasts.

The insects are still there, Byrne says, “but not in the overwhelming numbers that awed or frightened us years ago”, says the scientist, whose work has shown how lost dung beetles navigate their way home by looking at the Milky Way.

It’s like losing the dark skies and our view of the Milky Way. “We won’t miss these things if we never knew them, but another part of our natural heritage has slipped away, barely being noticed.”

We can’t exist without insects because they affect every aspect of our lives and are crucial to the ecosystems we depend on, says Catherine Sole, an associate professor in systematic and evolutionary entomology at the University of Pretoria.

These tiny creatures, often unnoticed, pollinate our fruit, vegetables and flowers, recycle nutrients, control pests and are food for birds, bats, reptiles, amphibians and fish.

As the most numerous and most diverse living creature on Earth, insects are the “little animals that run the world”, says Michael Samways, professor of conservation ecology and entomology at Stellenbosch University. “Insects are the little folks that are driving the making of the soil, pollinating the plants and our crops. All together they’re keeping the real biodiversity churning along with the other little animals. Our destiny depends on them and their survival.”

Insects, too, serve as food for livestock and humans “in an ever-expanding world population” and influence how we treat diseases, particularly genetic diseases.

Insects signal how healthy ecosystems are, particularly in water systems.

And how insects fly has allowed us to land probes on Mars and we have mimicked the ingenious way that earwigs fold their origami-like wings to fold cell phones and satellite panels.

Insects under siege

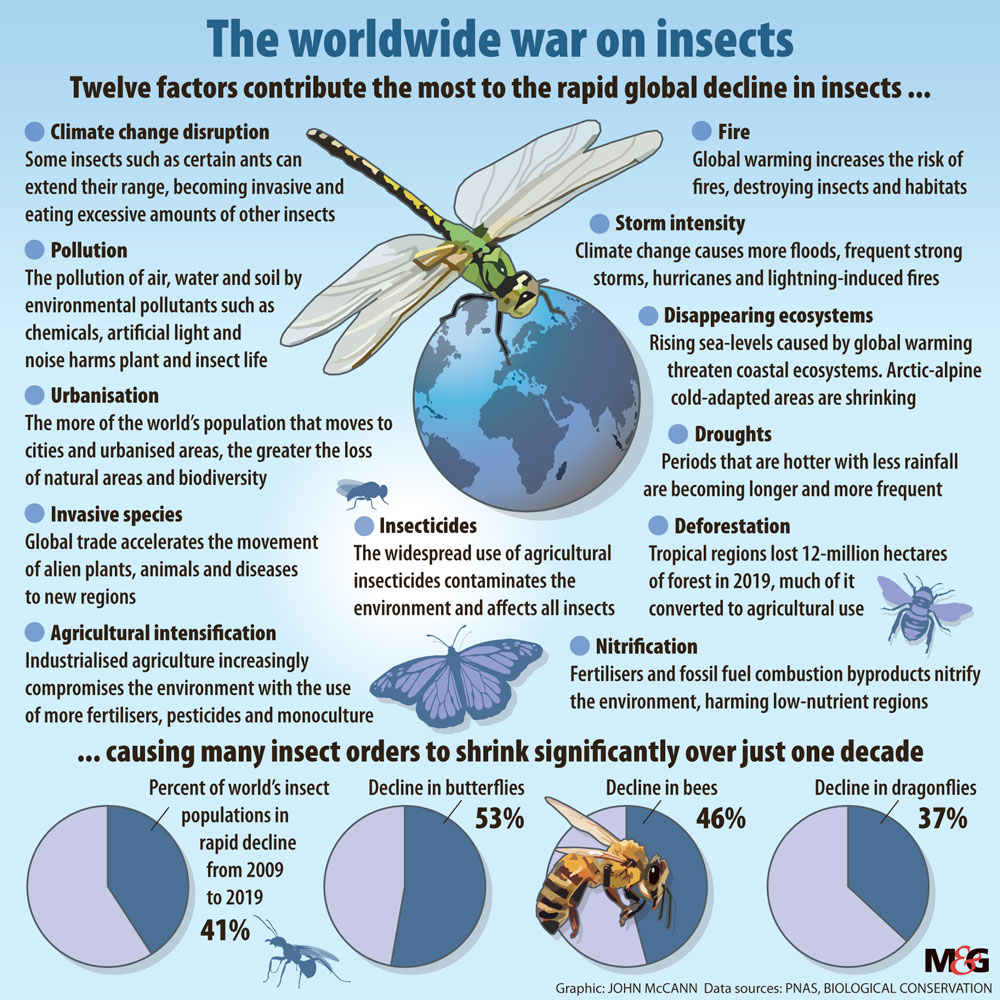

But insects are in trouble: nature is “under siege”, and insects are “suffering death by a thousand cuts”, a group of the world’s leading bug experts warned in a special issue of 12 studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) earlier this month.

Climate change as well as the destruction of habitats through felling forests and clearing land for agriculture are the main culprits for their dwindling numbers, together with pesticides, invasive species, urbanisation and light pollution.

The planet is losing between 1% and 2% of insects every year. “Severe insect declines can potentially have global ecological and economic consequences,” say the PNAS authors.

Outside of Europe and the United States, where most long-term insect data comes from, little is known about trends in the Americas, Africa and Asia, where most of the world’s insects are found.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

“If you look at all of the different groups that have been studied, whether it be hoverflies, which are important pollinators, as well as bees and wasps and other insects that are important pollinators, you are getting these declines,” says associate professor Chris Weldon, an entomologist at the Flies of Economic Significance research group at the University of Pretoria. This affects food security, he says.

Previously, it was thought that it was only uncommon insects that would be affected. But more research is showing how beneficial common insects like hoverflies are suffering.

Hoverflies mimic bees and wasps to mislead predators and are described as the helicopters of the insect world. “One paper that was in this special issue showed that the more common hoverflies, those are the ones that are disappearing … and that affects their diversity in the environment where they were sampling. That affects pollination,” said Weldon.

Climate change, too, will bring more common pests. “The more common and invasive species, they’re going to spread more, and you’ll get much more of them. They’ll replace the other insects that are disappearing.”

We don’t even know what’s out there.

More than a million insect species have been described as a species, but there could be a staggering 4.5 to seven million that remain unnamed. And those are the conservative estimates.

In South Africa, about 60% of insect species don’t have a name, says Byrne. “Because we don’t know what these insects do, we should hang on to them and find out.”

Most people view insects as pests, but only about 500 species are.

The PNAS lead paper describes how most of the world’s attention has been devoted to protecting rare, charismatic, and endangered species. But social media groups focusing on insects are flourishing as are the growing numbers of citizen science and education initiatives “to survey, conserve and raise awareness of insects and their importance”, it says.

European countries and Costa Rica have pledged millions of dollars on pollinator protection programmes while in the US, the fight to protect pollinators from toxic neonicotinoid pesticides has gone to court.

A protective dung beetle sitting on top of dung ball in the Kruger National Park

A protective dung beetle sitting on top of dung ball in the Kruger National Park

Most insects are magnificent, says Weldon and “if you take the time to look at them and at the way that they live their lives, they’re fascinating”.

The insects he works on are intriguing, even though they’re fruit pests. “My insects are quite cool. They have really interesting behaviours. The males perform dances to attract females; different species can live in toxic fruit that nothing else can eat. There’s a fruit fly species that lives on the beach in KwaZulu-Natal.”

Insects’ situation in South Africa

No one knows for sure what is happening with insects in South Africa.

The country, says Weldon, has terrible long-term records. “No one has really been looking at it … If you look at insects, you get huge differences between years and you need to sift through all that noisy data to pick up any long-term-trends then. You need in the order of 10 to 20 years’ worth of data to be able to see any of these declines.”

Anecdotal evidence of insect declines abounds, says Sole, such as people commenting that they don’t see many insects attracted to their lights at night anymore. “However, there is no long-term monitoring data to show that insects are declining scientifically.”

South Africa, she says, shares the same threats to its insects as the Global North: land transformation, pesticides and climate change.

Jeremy Dobson, who runs the Lepidopterists’ Society of Africa (LepSoc), which works to protect butterflies and moths, has little doubt that the insect apocalypse is real.

Samways, too, says South Africa lacks long-term data. “We know there is local extinction of certain species where they’ve been lost from certain areas. But by and large we don’t have that large scale drop in abundance as far as we can make out … or any sort of major loss of species. We do not see those same dramatic declines [as in the Global North].”

But South Africa’s variable climate has made many of its insect species flood, drought and fire resilient, says Samways, which means they can adapt to significant changes.

Our bees and wasps, for example, retreat to refuges such as kloofs or little pockets next to rocks to escape fires. Adult dragonflies, too, hide in vegetation among rocks right next to rivers where fires won’t reach.

Samways says the implementation of large conservation corridors between plantation forestry, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal, “has been absolutely fantastic” for conserving biodiversity.

“Some of the organic farming approaches and the integrated production of wine protocols where they’ve introduced very low levels of insecticides has been incredibly beneficial. On crops like citrus, there was a huge swing many years ago, over to bio-control and that has also really helped the insects.”

Our rivers, from an insect perspective, are pretty clean. “Keeping our headwater streams clean in the Drakensberg, or the Cape Fold mountains, up in Limpopo and in the Amathole mountains in the Eastern Cape has been really important because that’s where the real diversity is,” says Samways.

South Africa’s network of protected areas and conservancies, too, are playing a huge role. And the fact that the country has over half a million ponds and reservoirs also promote local insect diversity, he says. “We found that insects can actually use these artificial ponds to let them get through times of hardships from drought.”

The loss of land is the most worrying threat, particularly in the Cape Floristic region, he says, and the looming issue of insect mortality in the country from traffic and lights.

Bees and butterflies

South Africa is home to butterfly species, many of which are found nowhere else on Earth. But their numbers are plummeting.

Dobson says that local butterfly numbers are half of what they were in 1980. A recent assessment by LepSoc Africa found that 20 South African butterflies are critically endangered and five are presumed to be extinct.

A bee mimic hoverfly on a group of flowers.

A bee mimic hoverfly on a group of flowers.

Climate change is playing a part, and in the Western Cape, the encroachment of Port Jackson, an invasive plant, into coastal fynbos is wiping out rare butterflies.

He says human population growth and the inevitable habitat destruction and habitat deterioration associated with this drive insect declines.

It’s difficult, though not impossible, to optimise habitats to suit a particular butterfly species. But the main issue is retaining enough parks and undisturbed areas for butterflies to inhabit.

“In general terms, if there is suitable habitat, the insects will look after themselves. It seems possible that, in the long term, many species will not survive being restricted to increasingly small and isolated environments, but this is probably the best that we can hope for.”

In December 2020 the Monarch butterfly was denied the listing as an endangered species. Since 2008 this migratory species has declined in numbers by more that 80%. Each spring and again in the autumn, millions of Monarchs make the journey between the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico to the US and Canada. It takes 3 generations of Monarch to complete the journey.

In December 2020 the Monarch butterfly was denied the listing as an endangered species. Since 2008 this migratory species has declined in numbers by more that 80%. Each spring and again in the autumn, millions of Monarchs make the journey between the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico to the US and Canada. It takes 3 generations of Monarch to complete the journey.

According to a global analysis of bee declines released last week, wild bee species have plunged by a quarter since 1990.

In South Africa, Weldon says, beekeepers have witnessed significant losses in the colonies they manage. “We have lots of wild bees, and it’s easy to replace them, but the colonies, they’re losing those quite rapidly.”

Climate change, insecticides and the spread of diseases are playing a role in bee declines.

South Africa, he says, has a special case. “There are two different types of bees — originally from the Cape and another further north. The one from the Cape when it was accidentally introduced to the north became a parasite of colonies. It invades the northern bees’ colonies, and then the northern bees treat that parasitic bee like a queen. They feed it and neglect their brood, and this causes the collapse of the bee colony.”

Samways also sees climate change evidence on insects that show the “disconnect” between insects and flowering plants. “We don’t want the plant to be flowering at one time, and the bee is emerging at another time.”

Elevated CO2 levels and dung beetles

Claudia Tocco carries a container filled with dung beetles and animal droppings into the Conviron, a carbon dioxide growth facility at Wits University that resembles a walk-in fridge.

The postdoctoral fellow at the school of plant, animal and environmental sciences has discovered how elevated levels of CO2 can affect dung beetles. There was higher mortality rate when the CO2 was higher, the beetles were smaller and required more time to develop than those at a lower level of CO2.

The findings are essential because size matters. “Size dictates whether you’re going to get sex or not and whether you get sex or not indicates whether you’re going to get your genes in the next generation,” says Byrne.

Many of the reasons cited for global insect declines are patchy. “That’s why dung beetles are our canary in the coalmine.”

Carbon dioxide is ubiquitous throughout the skin of the atmosphere, he says. “We think it’s been mediated by microorganisms in the soil and they are also ubiquitous … If this is indicative of what’s happening underground to ground living insects, the potential result is enormous, because about 40% of insects spend some time underground.”

Some things you can do to help insects

- Avoid mowing your lawn frequently.

- Leave old trees, stumps and dead leaves alone; they are home to countless species.

- Watch your carbon footprint.

[/membership]