Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago noted that high levels of economic uncertainty persist, as Russia’s continues to wage war on Ukraine. (Moeletsi Mabe/Gallo)

A lower inflation target could be on the table as early as next year. This is according to the national treasury, which told the Mail & Guardian this week that the target is part of its broader macroeconomic policy research agenda.

A lower inflation target must be agreed on by the finance minister and the South African Reserve Bank.

“The research will look at the costs and benefits of changing the target including, for example, implications for growth, the value of the rand and international competitiveness. When this research is complete — most likely early next year — we will be able to determine what changes, if any, are appropriate,” the treasury said.

“We continue to engage with the Reserve Bank on this and other matters through various standing committees.”

Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago recently told the Financial Times that there is a “compelling case” to lower South Africa’s inflation target. The current target range — between 3% and 6% — has been in place for 21 years.

Speaking with the M&G on Wednesday, as preparations were underway for the bank’s centenary celebration, Kganyago reiterated this stance.

“Firstly there is no virtue in higher inflation. Higher inflation begets high interest rates. If we want low interest rates we must have lower inflation,” the governor said.

Most major economies aim for low and stable inflation, and the Reserve Bank uses inflation targeting to protect the value of the rand. The inflation target affects the interest rate: As inflation threatens to breach the upper end of the target, interest rates will likely be hiked.

But many countries have much lower inflation targets compared to South Africa’s wider target range. Brazilian policy-makers are currently mulling over a more ambitious inflation target of 3% (down from 3.25%) for 2024.

Kganyago noted that the idea to lower South Africa’s inflation target is not a new one. In 2001, then-finance minister Trevor Manuel and Tito Mboweni, who was the Reserve Bank governor at the time, considered lowering the target range to between 3% and 5%. But between 2001 and 2002 the rand weakened significantly and the rate of inflation breached the upper band of 6%.

“As a result of that shock, the target was revised back to 3% to 6%. The correct thing to have done at that time was not to revise the target back, but say it will take us two to three years to come back to the lower target,” Kganyago said.

The Reserve Bank has not yet started having conversations about lowering the target, Kganyago said. “But I understand that national treasury is going through a macroeconomic process and they have asked us to be involved in that … and they would like to take a look at that target range,” he added.

“If that is the case, given the previous public commitments that were made by Minister Manuel and governor number eight [Mboweni], the target can only be revised lower. It can’t be revised higher.”

He added: “This is not complex research. This is the kind of research the staff of the Reserve Bank and the treasury did before in 2001.”

Most emerging market economies have revised their targets lower in recent years, Kganyago noted. “And so if South Africa revises its target, there isn’t scope to revise it higher. It must be lowered. Because for us to be competitive, our target range must be close to or the same as other emerging markets.”

A good time

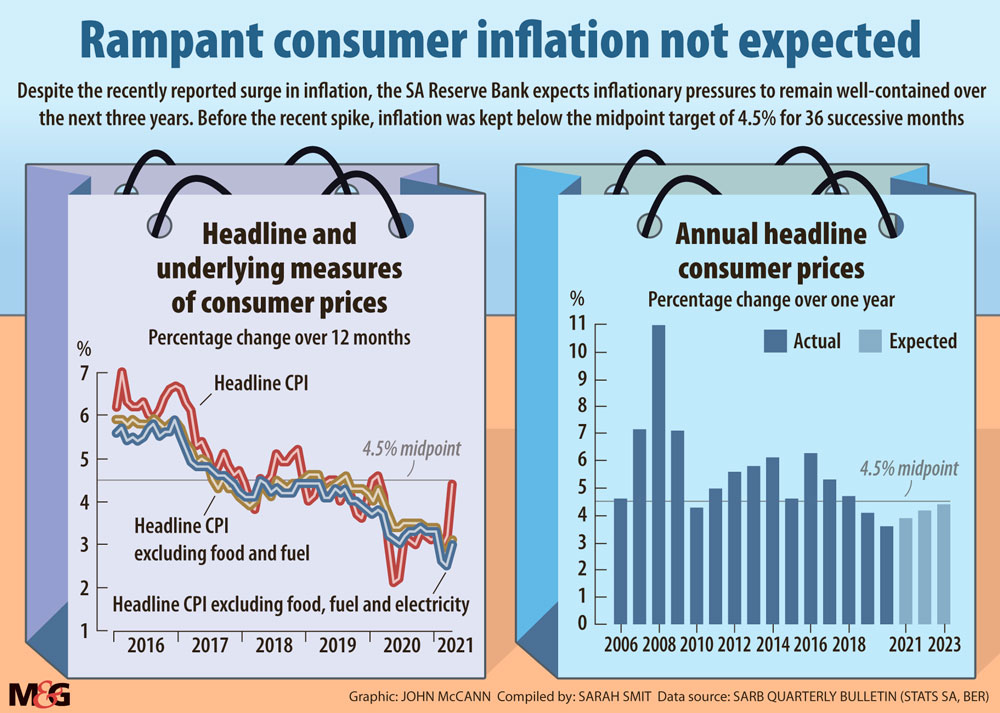

Prior to the recently reported spike, inflation remained below the South African Reserve Bank’s 4.5% midpoint target for 36 months in a row. This track record — as well as expectations that inflation will remain contained below the midpoint for the next two years — are signs that the country is primed to lower the target range, experts say.

Citibank economist Gina Schoeman said: “The governor has been successful in anchoring inflation expectations from the top of that range at 6% all the way down to 4.5% or lower. And this has got some huge benefits for an economy that still deals with inefficiencies and the risks of overly high wage demands.

“It’s not to say that you don’t want to pay people more. It’s just that if all price increases are somewhat aligned in any economy, then the economy is better overall. And in any economy most price increases will usually be aligned with inflation expectations.”

The current inflation environment makes lowering the target much easier, Schoeman said. “But what actually makes it the best time is the fact that we have now had many years of inflation, and inflation expectations, well below historical averages. So we’ve proved that the economy has gotten used to — and is better off — with a lower inflation trajectory.”

If a lower inflation target is set in 2022, it will be “quite nicely overlaid with the beginning of the governor’s second term,” Schoeman added.

Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings agreed that the current conditions make it a good time to lower the target. When the 3%-to-6% target range was initially set, inflation was breaching the upper band, Lings noted.

“We set an ambitious target, and there were discussions at the time on whether we should start off with a target that is in line with where inflation was at the time. It was felt that that was not the inflation rate we wanted and therefore it was not ambitious enough.”

Lings added: “I think now is a good time, because we’ve had successes. It is starting to become more accepted that the target is actually 4.5%. I would use this opportunity to entrench that idea.”

But, he said, bringing the target to 3% or lower is too much of a policy risk. “While we have been down to 3%, it doesn’t feel like we are necessarily able to achieve that. Clearly South Africa needs to go through a much more ambitious growth spurt and that may be accompanied by a little bit more inflation.”

Others are less roused by talk of lowering the target. Trade union federation Cosatu’s parliamentary coordinator Matthew Parks said the trade union federation agrees that inflation must be managed.

“But we see that inflation has been kept, for quite a long time, in a manageable space … Our disagreement with the Reserve Bank is that they have only focused on inflation. They have not lifted economic growth and job creation. So they have basically abandoned those responsibilities and have just solely focused on those points.”

Responding to criticism that the Reserve Bank is overly focused on inflation targeting, Kganyago said: “Inflation is the enemy of the poor and it is the enemy of people with a fixed income … So that is why you need an independent monetary authority tasked with controlling inflation — to build credibility and demonstrate to the price-setters and wage-setters that it can contain inflation.”

[/membership]