Back foot: After his expulsion from the ANC, Julius Malema went to Gold Fields’ mine near Carletonville to campaign for the nationalisation of mines. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

NEWS ANALYSIS

In 2012, the former chief executive of the JSE, Russell Loubster, called the ANC Youth League under Julius Malema “a consumer of value and destroyer of confidence”.

Loubster’s remark, made during a public lecture at the University of the Witwatersrand, came a year after the youth league marched from the Johannesburg central business district to Sandton to deliver a memorandum of grievances to the stock exchange.

The march on the JSE on 27 October 2011 formed part of the youth league’s call for economic freedom, which, in its view, included the nationalisation of South Africa’s mines. The entreaty to nationalise mines shook investors and drew the attention of ratings agencies.

Heyday: Then ANC Youth League president Julius Malema (centre) leads his supporters on a march to the JSE on 27 October 2011. (Nelius Rademan/Gallo Images/Foto24)

Heyday: Then ANC Youth League president Julius Malema (centre) leads his supporters on a march to the JSE on 27 October 2011. (Nelius Rademan/Gallo Images/Foto24)

In the decade since, Malema has forged ahead with his economic campaign, taking on the business sector on various fronts. But without the ANC, and with little power to sway policy, Malema is not the destroyer of confidence he once was.

Political economist JP Landman said Malema has lost considerable influence since being expelled from the ruling party in February 2012: “Over time the distance between him and the ANC got bigger, not smaller.”

Malema and his Economic Freedom Fighters have managed to drum up considerable media attention, Landman noted. But “even with the ANC’s decline”, this attention has not quite translated into electoral votes.

Most recently, Malema got some media attention when he visited various restaurants to check employment ratios between South Africans and foreigners.

In the past, the EFF has managed to muster considerable airtime by targeting the business sector. In 2018, members of the EFF stormed H&M stores around the country after the Swedish clothing retailer received backlash for a racist ad. The party has waged similar campaigns, each resulting in the vandalism of stores, against Vodacom and Clicks.

A general view of EFF supporters protesting at Mall of Africa during the national shutdown of all Clicks outlets on 7 September 2020. (Luba Lesolle/Gallo Images via Getty Images)

A general view of EFF supporters protesting at Mall of Africa during the national shutdown of all Clicks outlets on 7 September 2020. (Luba Lesolle/Gallo Images via Getty Images)

Still, the fallout from these incidents does not compare to what happened when Malema — then the leader of the ANC’s youth wing and tipped by some as South Africa’s president-in-waiting — popularised calls to nationalise South Africa’s mines.

His nationalisation battle cry rippled through the mining sector, putting a damper on investment by stoking uncertainty.

Business and political journalist Tim Cohen, who wrote A Piece of the Pie: The Battle Over Nationalisation, said when the discourse about nationalisation popped onto the political agenda after 2010, mining houses put local investment on hold.

“The next thing that happened was that they [miners] started investing outside of South Africa in a much more assertive way.”

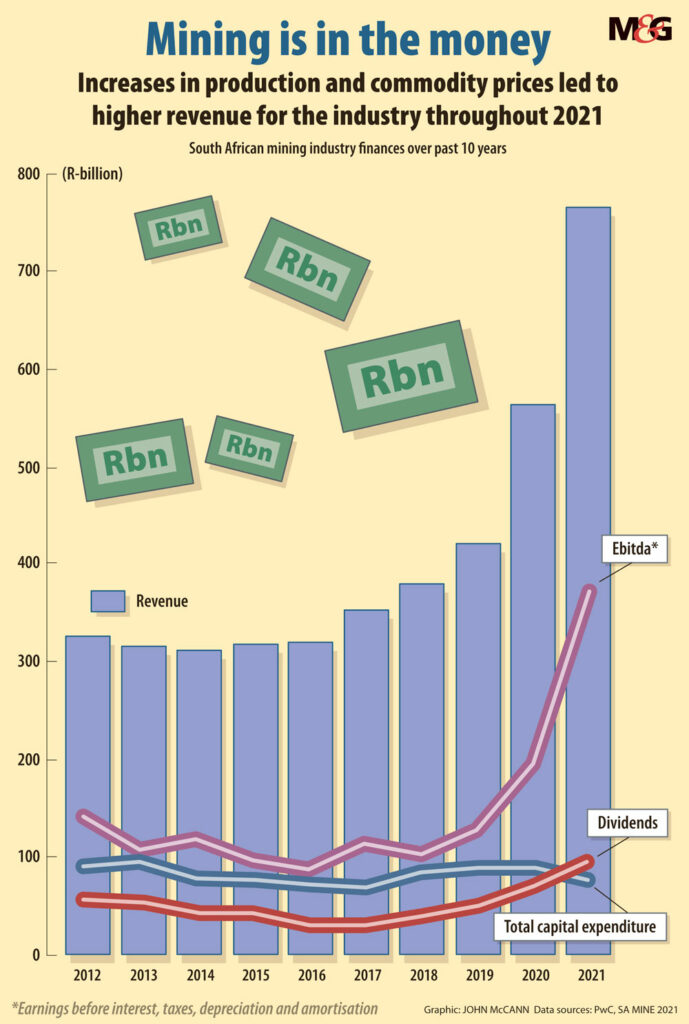

Mining production, Cohen noted, has been static for almost a decade. “The mining industry just went on ice. And that makes sense, because it was a very uncertain time. Miners were not convinced that nationalisation would take place, but they hedged their bets a bit.”

In 2011, Moody’s downgraded South Africa’s credit rating from stable to negative. Moody’s cited South Africa’s political risk and noted that the governing party’s “unwillingness to definitively reject demands from certain segments of the political spectrum for more activist policy interventions was harmful to South Africa’s economic prospects”.

One thing that would have concerned ratings agencies was how calls for nationalisation would affect the national debt, Cohen said. “What they were worried about is that South Africa’s biggest exporter would experience a decline. That would have repercussions for the finances of the state.”

The day after the Moody’s downgrade, Malema was suspended from the ANC after being accused of sowing divisions in the party.

In 2012, he was officially expelled. A year later, Moody’s seemingly rewarded the ANC’s decision to distance itself from the politician by not downgrading the country any further.

The headline issues on the national agenda changed quickly, Cohen added. “The South African narrative moved on. So there was a positive upswing when the ANC kind of distanced itself from nationalisation — though it never really did in a very determined way … The caravan sort of moved on, first from rising mining costs, to Eskom to state capture.”

In 2010, Cohen noted, calls to nationalise the mines were popular. “Because at the time the mines were just printing money. But in the economic decline post-2010, the mines started to do less, which made them less attractive targets.”

Four years after the EFF was formed, Malema found another compelling political foothold: land expropriation without compensation.

In 2017, the EFF tabled a motion to amend section 25 of the Constitution to allow for the expropriation of land without compensation. The motion was defeated, but a year later the party tabled another motion, which the ANC amended to point out that expropriation should not harm the economy.

After a public participation process, the review committee reported back to parliament, recommending that section 25 be amended.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)In December 2018, parliament published a draft Expropriation Bill, which noted that it “may be just and equitable for nil compensation to be paid where land is expropriated in the public interest”. The Bill is expected to form part of the parliamentary process for adoption in early 2022.

One of the reasons for the EFF’s turn to expropriation without compensation, and away from mine nationalisation, is that land has a far wider appeal, Cohen said.

In August 2018, ratings agency Fitch cautioned that the rhetoric about land expropriation would dent investor confidence.

In an analysis of business confidence in the first half of 2018, the Bureau for Economic Research at Stellenbosch University noted that positive sentiment surged when Cyril Ramaphosa, a former businessman, became president. But this upturn in confidence was stifled by policy uncertainty about land expropriation.

Fitch was watching the ANC and its new president — not Malema — for signs of whether rhetoric would become something more. The agency’s warning came after Ramaphosa announced a decision by the ANC to push ahead with a constitutional amendment.

By taking this stance on land reform, Fitch said, “we believe Ramaphosa is attempting to ensure that the left-leaning political parties such as the Economic Freedom Fighters do not control the national narrative on land reform or take a significant chunk of votes from the ANC in the national election”.

Landman said Malema’s loss of influence was well illustrated in the vote on amending section 25.

In December the national assembly voted against the ANC’s section 25 amendment after the governing party failed to drum up support from the EFF. The amendment that eventually made it to parliament was too far removed from the EFF’s initial vision. The party called the amendment a “sell-out arrangement”.

Malema and the EFF got the section 25 conversation going, but without the power he once wielded by being in the ANC, he had little influence over where it went.

Confidence is won and lost on the back of policy decisions and their fallout and — unless his proximity to power is restored — Malema may never rattle investors as he did with the governing party in his corner.

[/membership]