Finance minister Enoch Godongwana.(Brenton Geach/Gallo Images via Getty Images)

Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana’s budget speech last month set its sights on a brighter economic future. The economy is expected to reach pre-pandemic GDP this year and, according to the budget, a R182-billion revenue windfall has set the economy on a better course — towards the end of fiscal consolidation.

This week, data from Statistics South Africa confirmed the economy’s modest rebound last year. According to the data, South Africa’s GDP grew 4.9% in 2021, driven mainly by higher economic activity in the finance, personal services and manufacturing sectors.

But analysts point out that the country’s GDP growth is still far too low to stave off unemployment and possibly another bout of social upheaval. It is likely that, after enduring more than 10 years of anaemic economic growth, South Africa may be staring down the barrel of another lost decade.

In his foreword to the budget review, tabled towards the end of February, treasury director general Dondo Mogajane gave a hopeful evaluation of South Africa’s economic future. “There is a light at the end of the tunnel,” he said.

The dark tunnel Mogajane was referring to is the economic slump South Africa has found itself in for more than a decade. Growth slowed markedly after the 2008 global financial crisis and has not recovered since. In the decade before 2008, GDP growth was 4% a year. But, between 2010 and 2019, economic growth slowed to just 1.7% a year.

In 2016, the treasury’s budget review noted that GDP growth had fallen behind the rate of population increase, resulting in declining per capita incomes. “In other words, the average South African is becoming poorer. Lower rates of economic growth reduce government revenue, undermining the state’s ability to sustain spending on core social and economic programmes,” that budget review read. “While global factors play a strong role, domestic growth has continued to diverge from the world average.”

According to a working paper by economists led by Harvard professor Ricardo Hausmann, between 1999 and 2008, GDP growth in South Africa was high enough to sustain income per capita gains of 2.6% a year. But, between 2010 and 2019, average incomes rose by only 0.15% a year.

Over the past 15 years, the paper noted, the share of exports and investment in output fell while government spending rose. South Africa’s exports volumes barely surpassed their 2007 levels in 2019 and have steadily lost global market share since 2015. Meanwhile, overall investment fell from 21% of GDP in 2007 to 17% in 2019. This was essentially driven by private investment, which fell from 15% of GDP in 2007 to 12% in 2019.”

In 2020, the paper added, “investment and exports plunged, whereas private consumption was not equally hit, and government consumption increased in real terms, consolidating the decade’s trends”.

South Africa’s GDP contracted by 6.4% in the Covid-19 pandemic’s first year. Although the economy has rebounded, buoyed by strong commodity prices, the treasury now expects that real GDP will grow by only 2.1% in 2022 and average 1.8% over the medium term — just a sliver above the average growth rate over the past decade.

According to the Statistics South Africa data released this week, the economy is still 1.8% smaller than it was prior to the pandemic.

The low growth has resulted in a deepening unemployment crisis. In 2008, the country’s expanded unemployment rate was 23% and has trended upwards since. In 2019, prior to the pandemic, the unemployment rate breached 30% and, in the third quarter of 2021, it was 46.6%. South Africa has the highest unemployment rate in the world.

The budget suggests South Africa is exiting the dark period, during which low economic growth weighed down on development, and entering a new phase. But economists are not convinced that, even in the best case scenario, GDP growth will be enough to sustain the government’s development goals.

“When I was listening to the treasury’s forecast and the minister’s budget speech, I thought that that growth rate is going to keep us stuck at where we were pre-Covid, which was lower than population growth,” said Lullu Krugel, PwC South Africa’s chief economist.

If South Africa does not break out of the low-growth cycle unemployment will continue to rise. “We will continue to see the unemployment rate trending upwards. And unfortunately, as we saw last year, even if the economy is recovering, employment does not seem to respond to that,” Krugel said, adding that higher rates of joblessness will jack up social pressure.

“If you look at last year and what happened with the July unrest, it was kind of the perfect conditions. The dry wood was there, you just needed the right thing to light the fire. If we are stuck in this low growth rate for longer, you make the conditions for something like that to happen again.”

The government needs to encourage private-sector investment to turn the tide on low growth, Krugel said. Bringing the private sector back into the fold was a key talking point in President Cyril Ramaphosa’s State of the Nation address and in Godongwana’s budget speech.

Dick Forslund, the senior economist at the Alternative Information and Development Centre, said the treasury always overestimates GDP growth. “It is almost without exception … So that’s the first thing I think of when I read the numbers.”

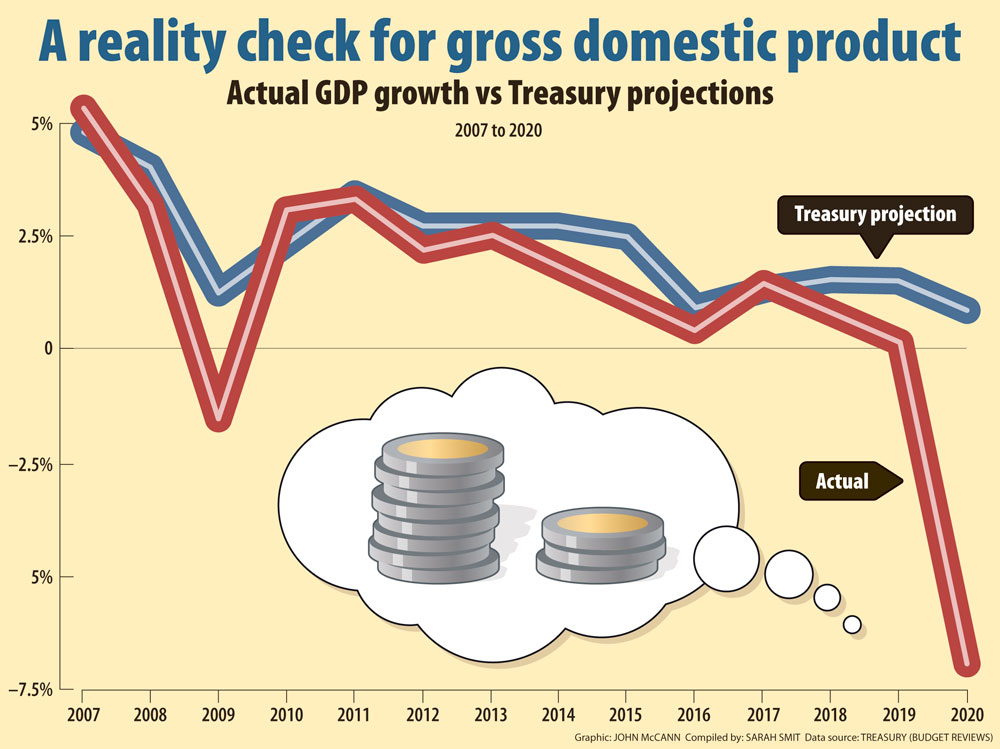

The Mail & Guardian compared the treasury’s GDP growth forecasts going back to 2007 to the actual GDP growth for those years. According to the M&G’s analysis, the treasury almost always expected a higher growth rate than what was reality. The treasury’s forecasted growth rate was only lower than the actual growth rate in 2007, 2010 and 2017.

Forslund said the government is hinging its growth prospects on structural forms, which “diminish the public sector as a share of the economy and hopes to crowd in private investment”.

“Treasury’s projections are based on this theory that this will materialise. And I believe it is wrong … Even if all things are equal, I think they are basing their projection of real GDP growth on wrong assumptions. I think they will be wrong. They will fail.”

Forslund explained that South Africa’s economic growth prior to the global financial crash was buoyed by the commodity boom at that time. But even in the wake of this growth South Africa’s unemployment rate outpaced the rest of the world.

That growth, he said, “was to the joy of the finance industry and to the joy of the owners of capital, but for the rest of the population it was not so”.

Forslund noted that research by University of Cape Town professor Martin Wittenberg, which found that wage increases between 1994 and 2011 disproportionately benefited high income earners. “For the rest, their living standard and wages were stagnant … So that bout of growth between 2004 and 2008 didn’t really benefit the majority of the population,” Forslund said.

“There is nothing to say that, if there is higher GDP growth now, that it will also not be so-called jobless growth.”

Duma Gqubule, the founding director of the Centre for Economic Development and Transformation, said the current GDP number reflects “a technical bounceback that has nothing to do with the economy”. This has been borne out in the fact that the rebound has been accompanied by higher levels of unemployment, he added.

He said the government needs to change its economic policies. “Treasury forecasts 1.8% for three years. That means they don’t believe in their own economic recovery plan. So there is no one who believes that the economic recovery plan will deliver even a percentage point of economic growth.”

Gqubule called the period of declining growth between 2009 and 2019 “a lost decade”. “Unemployment numbers have soared since 2008. We had no growth for the decade before this and now we are heading to a second lost decade.”

[/membership]