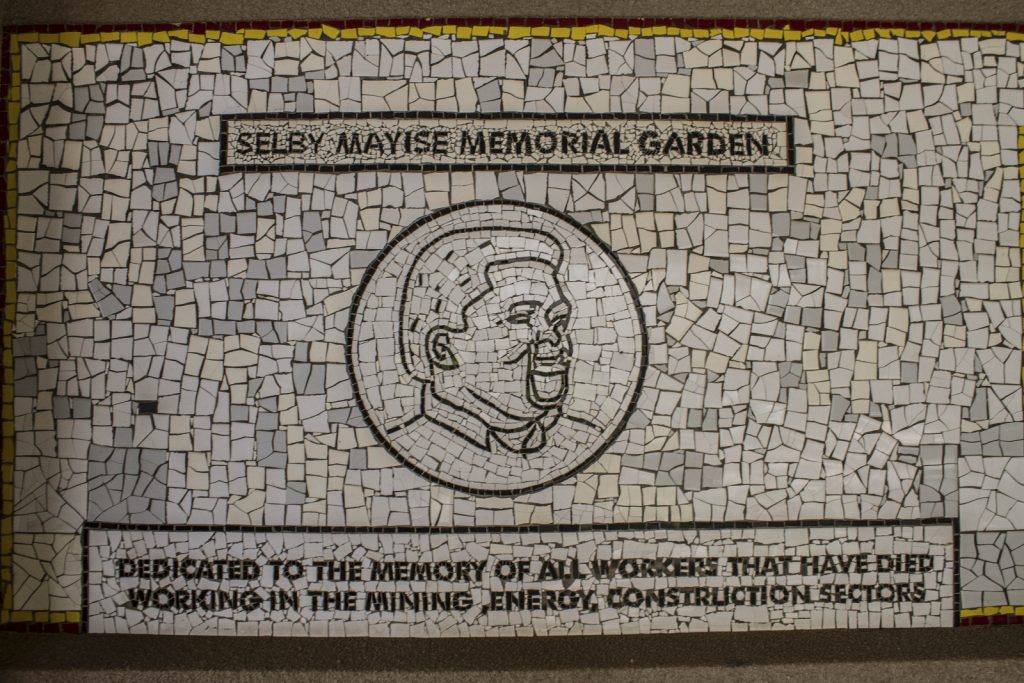

One of Andrew Lindsay’s mosaics in Bezuidenhout Road, Bertrams (near Ellis Park). This one represents the 1922 Miner’s Strike.

On a Monday morning In October 2021, a Centurion Mall jeweller arrived at his shop to find armed robbers fleeing with a trolley of stolen valuables. They shot him dead.

The pitiless crime has faded from the headlines, but for the dead man’s family — married for 25 years, he was the father of four children— it is still devastatingly present.

He* was a pious Jew who, it is said, more than once came home without shoes after giving them to a beggar.

Just a day later, South Africa lost another virtuous man to widely shared grief: artist Drew Lindsay collapsed and died of a heart attack in his Spaza Art Gallery in Troyeville.

The two men were further linked in death: when the jeweller’s family decided to commission a commemorative mosaic at the Linksfield Shul where he worshipped, they approached the Spaza Mosaic and Public Art Team Lindsay had founded.

Drew Lindsay with one of the pieces he produced with Hannelie Coetzee at the Weinberg Family Park in Waverley, Johannesburg. (Photo: Gail Wilson)

Drew Lindsay with one of the pieces he produced with Hannelie Coetzee at the Weinberg Family Park in Waverley, Johannesburg. (Photo: Gail Wilson)

The ribbon-like creation, 11m by 31cm, would be installed on the back of a bench at the entrance to the synagogue. Its theme was the Tree of Life, an ancient symbol of human connectedness with the Earth and the heavens, the axis mundi, shown as a writhing mass of flowering and leaf-bearing branches springing from a downward-flowing trunk.

Embedded in the foliage would be customised tiles of a chameleon, frog and other life forms fired by ceramic artist Lisa Lieberman; biblical fruits such as the pomegranate; and Judaic symbols such as a Cohen’s breastplate — historically worn by the high priest of the Israelites — in 12 colours denoting the tribes of Israel.

Lindsay was a public artist dedicated to rescuing art from the sterile, air-conditioned spaces of the Goodman and Everard Read galleries to the mean streets of downtown Johannesburg, steadily sinking under squalor and decay.

His mosaics, dotted about the central city, attest to his humanist sympathies. They include the fanfare to miners at the National Union of Mineworkers’ head office; the Kliptown memorial to Umkhonto weSizwe fighter Petrus Molefe; and the Martin Luther King steps in Troyeville.

At Ellis Park is a tableau he designed of the 1922 Rand Rebellion; in a flyblown lot in Kensington, a mosaic-covered wall recalls the men of the district killed in the 1914-18 war.

Amid dog turds, scraps of food and crumpled newsprint the latter stands conspicuously unvandalised on a dreamlike white ground, Flanders poppies blow and grey phantoms float, tied together by trenches, gas tape and barbed wire.

In The Wilds gardens are further examples of the team’s endeavours — a portrait of Jock of the Bushveld, fountains, and a bench dedicated to Lindsay that he inadvertently worked on — alongside scores of outdoor sculptures by James Delaney, another cultural warrior intent on reclaiming abandoned spaces.

This art was not just for the public. Increasingly towards the end of Lindsay’s life, it was by the public. With a strong preference for collaborative projects, he set out to promote creative expression by South Africa’s “wretched of the earth”, giving them skills, workspace and an outlet for their artworks.

He started with rural craftsmen and recyclers, and worked with the latter on mosaic street numbers. Over time, he came to anchor a loose affiliation of mosaicists and other artists in Troyeville, Jeppestown, Bertrams and their decaying environs, some professional, some newly fledged.

They are Joburg’s uncelebrated cultural heroes, who strive, largely unnoticed, to redeem the blighted inner city.

Approached through a broken gate and a garden dominated by a Telkom tower bristling with discarded plastic bottles, Lindsay’s Spaza Gallery in Troyeville follows a street-level aesthetic of the abandoned, discarded, reused, broken and pieced together.

Everywhere there are off-centre surprises: a naive sculpture of a crowned crane peeps through bamboo; a David Rossouw mobile balances a model helicopter with a caged rock; a statue of a woman poses with a flower pot on her head.

One wall bears a collection of painted plates, many broken and glued together. On surfaces everywhere — floors, walls, tables — mosaics proliferate.

A few of the 2 600 works Lindsay left to the Spaza Gallery Trust are by established artists such as William Kentridge and Steven Cohen. But most speak poignantly with the voices of rough sleepers, trolley-pushers, illegal migrants and others on the margins, some of whom received Spaza residencies.

Still hanging by a thread, the mosaic-making continues. The Mail & Guardian visited a makeshift studio on the upper floor of an old engineering works in Jeppestown where the Linksfield shul mosaic was nearing completion.

On all sides hang the colossal canvases of Neo Ramushu-Mokgoshing, a self-taught painter from a Limpopo mining background who negotiated the space and invited other artists to share it. Mining and minerals are the material of his paintings, both as a subject and source of pigments and textures.

Dionne Macdonald, part Greek, part Scottish and wholly Bohemian, was Lindsay’s close collaborator.

An open-air artist since her teens, initially as a creator of costumes and floats for carnivals, she now drives the mosaic business with a shifting, racially diverse partnership of downtown co-workers.

The shul mosaic is charged with esoteric symbols, including a hamsa — an ancient apotropaic talisman used by both Jews and Muslims to ward off the Evil Eye.

Some Islamic scholars write of a moral, rather than metaphysical Evil Eye, identifying it with the sin of envy, a “sickness of the heart” and “gateway sin” closely linked to violence.

Envy and greed obviously drove the jeweller’s killers. But one can steal without killing, invade a house without torturing and raping, hijack a vehicle without driving its owner around in the boot for hours and then setting it alight.

Evil is quite unlike run-of-the-mill malfeasance. Nihilistic and inhuman, it is blind to the lives of others and stonily indifferent to their suffering. It preys on the weak and defenceless, the old, women, children — and the unarmed.

Its perpetrators have been spiritually disfigured, perhaps by racial, ethnic or xenophobic hatred.

They are the brutalised black and white South Africans who, to repeat former police reformer Meyer Kahn’s comment, “have no souls”. Bringing them back from the encroaching darkness into the fire-circle of the human family is one of the immense tasks facing the country.

Perhaps Lindsay’s most majestic conception is the circular Wellness Wheel in Indwe (blue crane) Park, surrounding the former South African Breweries building in Braamfontein.

Six metres across, it makes an explicit connection between health and the city. A polychrome riot of medicinal plants, fungi, insects and organically inspired ceramics, some pressed from leaves, it signals important Johannesburg landmarks such as the Mandela Bridge and The Wilds at every point of the compass.

At the Troyeville studio, completed, stands another magnificent Tree of Life, commissioned by the Johannesburg branch of the Indian-based spiritual movement Brahma Kumari. It makes the same point: art can heal; nature can heal.

The Kumari plan to display the work, and others like it, in peace gardens across the country.

The jeweller’s family is seeking to do more than commemorate. His sister, a psychologist, explained that the purpose of the shul mosaic is to try to find meaning in the tragedy that has engulfed them, to bring light into darkness and beauty from disfigurement.

As an art form, the mosaic is symbolically suited for this purpose. It is a public statement intended to have a lasting influence. (Macdonald says cut commercial tiles were preferred over the square, swimming pool type because they are more durable). And it restores from shattered fragments a new and aesthetically pleasing whole.

The Tree of life theme was inspired by the shul itself, where it features on glasswork and in a mural that promises life in abundance to those who “grasp it and … uphold it … Its ways are ways of pleasantness and all its paths of peace.”

Two of the murder suspects, held and charged three days after the killing, have the exact profile of the inner-city denizens Lindsay tried to reach. Twenty-six and 27 years old, they were arrested in Hillbrow, allegedly in possession of the murder weapons. One was wanted in connection with another armed robbery.

Such people may seem too spiritually calloused to rehabilitate. But Macdonald insists that redeeming broken Johannesburg and its inhabitants is the goal of public art.

She cites The Wilds, considered a no-go area under apartheid but now transformed by outdoor art and in wide use, and the Wellness Wheel, which Lindsay saw as a way of bringing nature back into the city.

“During the Covid lockdown I decided that we artists have a responsibility to create a vision of the future we want,” Macdonald said. “Art has the potential to change the viewer; all over the world it has been cited as having the power to uplift neighbourhoods.

“Public art should have the effect of lifting people’s spirits. Our job as artists is to help change the story.”

* The family asked for his name to be withheld.

Drew Forrest is a former political editor and deputy editor of the Mail & Guardian.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.

[/membership]