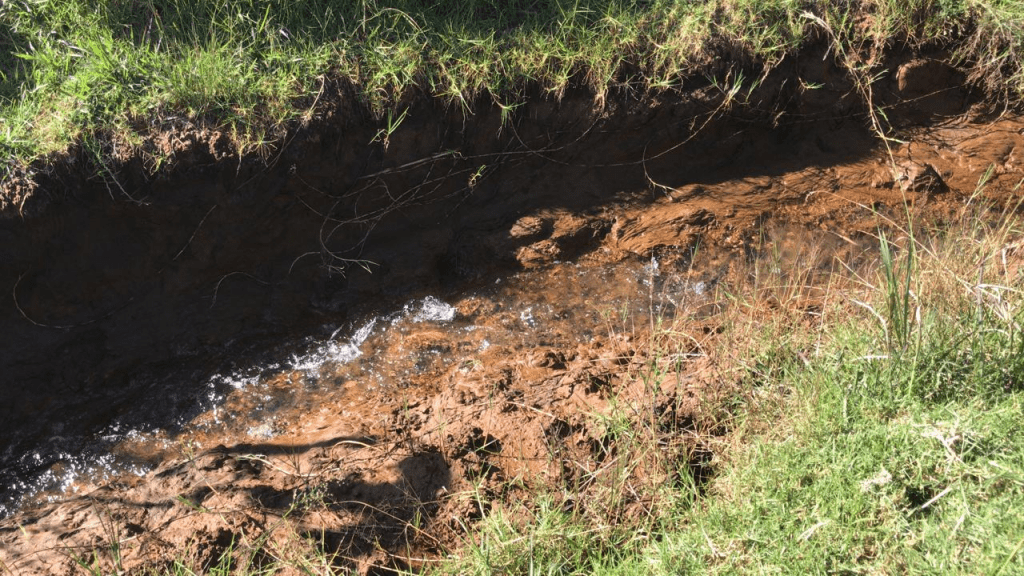

Degradation: Acid mine drainage (AMD) flows out of the Western mining basin on 12 April. Photos: Trevor Brough

The state’s short-term solution for the treatment of toxic acid mine drainage (AMD) on the Witwatersrand’s goldfield is “suboptimal”, an environmental justice activist said.

AMD, which is a legacy of more than 120 years of gold mining on the Witwatersrand’s goldfields, is caused when water flows over or through sulphur-bearing (pyrite) materials forming solutions of acidity.

It is characterised by low pH (high acidity), high salinity levels, elevated concentrations of sulphate, iron, aluminium and manganese, raised levels of toxic heavy metals such as cadmium, cobalt, copper, molybdenum and zinc, and possibly even radionuclides.

“The gold mining industry in South Africa, principally the Witwatersrand goldfield, is in decline, but the post-closure decant of AMD is an enormous threat, and this could become worse if remedial activities are delayed or not implemented,” said Mariette Liefferink, the chief executive of the Federation for a Sustainable Environment.

In 2011, the department of water and sanitation implemented its short-term intervention for the Western, Central and Eastern basins of the Witwatersrand goldfields and to protect the environmental critical level (ECL) in the central and Eastern basins, to safeguard aquifers.

This short-term solution, which is run by the Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority (TCTA), included the upgrading of the Western basin AMD treatment plant in Randfontein in 2012 and the construction of the central (Germiston) and Eastern (Springs) basins treatment plants, in 2014 and 2016 respectively, at a cost of R2.6 billion.

These plants pump 180 million litres of acid mine water every day from the three underground basins, neutralise the acidic water and then discharge it into the Vaal River system and the Crocodile West river system, at a cost of R293 million a year.

But in recent months, problems have arisen at these three plants. On the Eastern basin, which is meant to pump 110 million litres a day, pumping stopped in February last year because of the scaling (corrosion) of the motors of the three deep-level abstraction pumps, with the rising water eventually breaching the ECL. Pumping only resumed in December.

In the central basin, the scaling of the motors of the pumps and the volumes of ingress or surface water entering groundwater because of increased rainfall, also breached the ECL. In February this year, the water level was just 3.5m from decant, Liefferink said.

This is when the flooded system “daylights” and flows into the environment, causing environmental degradation. Meanwhile, since December in the Western basin, excessive rainfall caused AMD to decant, gushing on the surface into waterways.

As no environmental impact assessment was conducted when the government decided on its short-term intervention, this has resulted in “unforeseen consequences”, including the effect of excessive rainfall patterns and the scaling of the motors of the pumps, she said.

Wanda Mkutshulwa, spokesperson for the TCTA, said the uncontrolled decant in the Western basin is “continuing due to a particularly heavy rain season”, starting from the end of last year.

“As there has been no rain in the last few weeks, the amount of uncontrolled decant has started to decrease, and it is hoped that it will stop in the near future, as the dry season commences.”

Since December, the TCTA has been manually dosing the water with caustic soda, as a temporary measure, with the intention to raise the pH level to between 7 and 9. The pH level is currently around 7.

“Because of the size of this AMD plant, it only operates on one pump and has been performing at near full capacity, pumping, on average, 34ML/day. The spare pump was taken to the central basin, to assist with the challenges being faced there, and, as these have been attended to, the spare pump is ready to be sent back to the Western basin,” she said, adding that the removal of the spare pump to the central basin did not affect operations at the Western basin.

On the central basin, the TCTA has installed the rebuilt central basin pump and “the plant is now operating sufficiently. However, due to the water level in the shaft, we are not able to use the pumps at full capacity,” Mkutshulwa said.

“The current water level is 45.55m below cap and the pumping capacity is, on average, 71ML/day. The Eastern basin water level is at 42.15m below surface and has an average capacity of 92ML/day pumping. There is no immediate threat of a decant in both central and Eastern basins.”

AMD is not only associated with surface and groundwater pollution, but degrades soil quality, aquatic habitats and allows heavy metals to seep into the environment, Liefferink said.

Long-term exposure to AMD-polluted drinking water may lead to increased rates of cancer, decreased cognitive function and appearance of skin lesions. Heavy metals in drinking water could compromise the neural development of the foetus, which can cause intellectual disabilities.

Water expert Anthony Turton said although AMD has gone off the radar, it remains an important issue that will persist for centuries, if not millennia. “The very reason Johannesburg exists in the first place is because of gold mining … The reality is that Johannesburg has got a mining legacy and that mining legacy is going to increasingly be linked to our ability to deal with the unintended consequences of mine closure.”

Although the short-term treatment of AMD reduces the high salt load in the water, the neutralised mine water still contributes 362 tons of total dissolved solids — salts — a day to the Vaal barrage catchment.

In the short-term treatment, the pH is adjusted using lime to make the water more alkaline. Most of the metals drop out, but if the neutralised water becomes acidic, the metals could become mobilised again, Liefferink pointed out.

Photos: Trevor Brough

Photos: Trevor Brough

Photos: Trevor Brough

Photos: Trevor Brough

The main concern is that AMD will not disappear. “It will remain a risk for many years after mine closure and AMD has the most costly socioeconomic and environmental impacts. The short-term solution will result in increased salinity in the integrated Vaal River system and that can also present water security risks because the Vaal is one of the main rivers to supply water to the economy and to the people.”

In its latest annual report, Rand Water noted that there are various point sources that discharge into the Vaal River barrage, including major treatment works as well as discharges from gold and coal mines. “The bulk of the salt load from defunct mines (about 180 ML/day) is discharged from the central and Eastern basins via AMD neutralisation plants into the Vaal barrage catchment area.”

The threat of AMD is partially mitigated through the implementation of the government’s short- to medium-term interventions.

“Although the acidity and heavy metals are neutralised and removed from the water, the discharge is still highly saline, with total dissolved salt values of more than 2500mg/ℓ. Irrespective of the quality of such water, these discharges will, over time, have major effects on the overall hydrology of the catchment,” Rand Water said.

The government has meanwhile postponed its R10 billion long-term solution for acid mine drainage — which involves turning partially treated acidic mining water into potable or industrial water through a process of desalination and selling it to consumers — because of fiscal constraints and to determine what the current salinity and hydrology status of the Vaal is, after several years of treatment.

The department said any strategy aimed at eliminating AMD would be “extremely expensive, complex and a huge burden on the fiscus”.

Together with the Water Research Commission and key players in the mine water sector, it has investigated “alternative long-term possibilities” to address the current AMD issues on the Witwatersrand. A report would be released soon, which investigates all possible scenarios for the “long-term beneficiation” of AMD for the region.

Johann Tempelhoff, an extraordinary professor at the South African Water History Archival Repository at North-West University, noted that “in the long-term as the costs of water increase, certain industries will be interested in making use of the processed AMD. That’s clearly on the cards because we are definitely running out of water.

“Increasingly, we have to accustom ourselves to the fact that used water in water systems, like the Vaal River barrage, the integrated Vaal River system, may be secondary water and you will need treatment plants downstream to process that water for human consumption, as is the case in Europe,” Tempelhoff added.