No choice: Illegal artisanal miners showed the Mail & Guardian where and how they do their job. Robert Chauke* and his colleagues work above ground, mining Johannesburg’s dumps that have not been adequately rehabilitated, causing environmental damage. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

It was just past noon when a burst of gunfire shattered the quiet in Georginia, Roodepoort, west of Johannesburg.

Gillian Stewart, leaning on her crutches, didn’t flinch. “It was only a few shots — five or six,” she said wryly. “One night, Chris [her husband] stopped counting at 75 … It’s got to the point where if it’s a burst like that, all you do is head inside swiftly.”

The gunshots came from the illegal gold mining encampment on a desolate stretch of unrehabilitated mining land behind her house. Stewart and her neighbours live in fear of the running gun battles between rival gangs of heavily armed illegal artisanal miners over territory and their shootouts with law enforcement officers.

In recent weeks, the violence has intensified. At the end of July, protests erupted in Riverlea, about 15km from the Stewarts’ home. Residents demanded that the police act against heavily armed gangs from the Zamimpilo informal settlement, an illegal mining hotspot, who have been killing each other in deadly turf wars.

Specialised units of the Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department (JMPD) and the South African Police Service (SAPS) launched crackdowns on Zamimpilo’s miners, who have now been displaced to the informal settlement of Jerusalema — another illegal mining hotspot — on Georginia’s doorstep.

Illegal artisanal miners showed the Mail & Guardian where and how they do their job. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

Illegal artisanal miners showed the Mail & Guardian where and how they do their job. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

On 17 August, about 45 women and 17 children from Jerusalema fled to the Florida police station, seeking refuge as warring factions exchanged heavy fire.

“What’s happening is that the zama zamas are having a turf war because they’re being evicted out of the area. They’re having a turf war over area and over equipment as well,” said Jaundre Compaan, a senior security officer in the tactical division of Help24.

Special operations in recent weeks by the JMPD and SAPS have involved breaking down the unattended shacks in Jerusalema which are being used for the storage of ammunition, phendukas (machines for gold refining) and mining equipment.

“Now they’re using this field here as an escape route away from JMPD because there’s not enough members, nor does JMPD know the pathways,” Compaan said. “Everywhere there’s holes, and little mining shafts. If you fall down one of those, your body won’t be recovered.”

Residents feel as if they are prisoners in their homes, said Werner Steenkamp, who has lived in Roodepoort all his life. “We hear their blasting with explosives and the shooting happens day and night. It’s really become bad.”

That the shootouts are spilling into the residential area fills his wife, Charlotte, with anxiety. “This used to be a once lovely place to live,” she said. “Now it’s horrible, it’s hell … When they shoot, they just shoot; you don’t know where the stray bullets go. It can hit any one of us.”

Thomas Holyoake, who has lived in Georginia for 17 years, said residents had to pay for private security companies because they cannot rely on the police to protect them. “I look over my wall and see them busy mining and nothing is happening … I’ve seen them be tied up, chopped up with an axe and I saw them shoot two guys in the back of the head. Man, I’ve seen so many horrific things here, it’s madness.”

Stewart’s husband, Chris, added: “We expect one day our houses will just disappear into a sinkhole because the mining is not being conducted in a professional manner. We already have roads collapsing in the area.”

Illegal artisanal miners showed the Mail & Guardian where and how they do their job. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

Illegal artisanal miners showed the Mail & Guardian where and how they do their job. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

City of Johannesburg mayoral committee member for public safety Mgcini Tshwaku said the gangs come aboveground between 5pm and 6pm and then process their gold with the phendukas from about 10pm to 1am.

“That’s when they now shoot up in the air, it’s a way of marking their territory and then also there is the turf war. When you come up with soil full of gold, they’re going to rob you,” Tshwaku said.

“The ones we have chased in Riverlea, they are going to areas like Jerusalema and Matholiesville … They start fighting among each other and it’s got worse now because of the displaced zamas going into new territories. They are fighting each other and the community becomes collateral.”

In the nearby suburb of Fleurhof, Godfrey Makomene showed the Mail & Guardian an illegal mining operation behind the primary school, where residents and companies have had to close numerous holes excavated by the miners.

“They were mining here at the school, blasting with explosives and shooting each other. They break down stormwater pipes, and sewer pipes to access water, to wash their gold and now this area is flooding with sewage,” he said, pointing to pools of sewage flowing through the field, pockmarked with holes and tunnels.

Makomene is part of the Greater Gauteng Communities Against Illegal Mining and Land Invasion, which represents Fleurhof, Meadowlands, Florida and surrounding areas.

Last week, it sent a letter to Mariette Liefferink, the chief executive of the Federation for a Sustainable Environment, requesting her urgent intervention in arranging a meeting between all stakeholders and the chief executive of First Westgold Properties (Rand Leases) and its directors on illegal mining, “which has now become extremely unbearable for our people”. The meeting will be held later this month.

“On a daily basis, we are experiencing serious and violent crimes committed by heavily armed illegal miners, which are taking place in the Rand Leases area. This area is a major hotspot for armed gangs,” the letter read.

It detailed how, 30 years after the mine in Florida closed down, surrounding neighbourhoods have “been living under serious danger due to the illegal miners which have flooded the area”. The cessation of mining without proper closure and remediation “has resulted in the proliferation of serious unlawful mining activities”.

“Many people have lost their lives in the area and some are left with irreparable post-trauma of being victims of criminal activities, which are taking place daily.”

In the hulking shadow of the mine dumps, Didimalang Rapoo, the secretary of the organisation, who lives in Meadowlands, is worried about the violence. “You can’t be safe in your home. We hear gunshots every night, and we are basically living in fear. It’s inhumane.”

She said a partnership between the government, private sector and residents is the only way towards sustainable development in the area. Their plan is to deal with the source of the problem — the gold dumps.

“These mines that have been abandoned and shafts that are left open are the sources. The solution is the controlled clean-up activity by the community … If we are cleaning up and closing, surely no zama zama will come back to open land that belongs to someone, that is fenced, secured and rehabilitated,” Rapoo said.

Over the past decade, the organisation had gone to various authorities seeking interventions to tackle the influx of illegal artisanal miners. “Now, we’re here. It is now glaring and the violence that comes with it, it’s not bearable.

Spillover: The violent turf war affects people living in suburbs such as Fleurhof (above), Florida and Meadowlands on the West Rand. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

Spillover: The violent turf war affects people living in suburbs such as Fleurhof (above), Florida and Meadowlands on the West Rand. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

“You are sitting there scared, and you are a parent to children who are scared of the gunshots. They don’t know what can come into the house. And to see their dad scared like that, it’s very defeating emotionally. The thing [illegal artisanal mining] was left to take care of itself and now it’s become like a monster,” said Rapoo.

In recent weeks, Gauteng Premier Panyaza Lesufi has appealed for thedeployment of the army and additional security forces to tackle illegal mining in the province.

For Tshwaku, the army should be the last resort. “We can have JMPD, TRT [tactical response team] units coming from the police and just be focused, all of us, and come together and go after these guys,” he said. “We need to close these areas, flatten them out, remove the soil, rehabilitate it and light it up at night.

“Then, who is going to go digging there and where are they going to do their phendukas? It means these guys, their mining activity must be underground, not up. When they fight, they must fight there, underground. If they kill each other, they must kill each other underground.”

Lesufi recently told news channel Newzroom Africa that the province is “under siege from people who are not citizens of this country”, people that “cannot be accounted for”, people that are “highly armed and we expect that the problem can be resolved by police that patrol on a weekly basis?”.

But illegal artisanal miners are not exclusively foreign; many South Africans are involved, according to David van Wyk, a chief researcher at the Bench Marks Foundation. “This is not a policing problem, it’s a mining problem and it is an economic problem. So, either we can turn this thing to our advantage or we can let it go completely out of control.

“You’ve got 6 000 abandoned mines — are you going to put soldiers on every abandoned mine? It really doesn’t make sense and the people who are suggesting this, and that’s the premier included, he’s not thinking and he doesn’t want to think because he thinks xenophobia is going to win him an election.”

Van Wyk said as long as mines are being abandoned and their workers retrenched without their pensions and other funds due to them, “you are going to have illegal mining”.

The kingpins behind the organised crime syndicates that fuel illegal mining and exploit miners need to be apprehended, he added.

“We estimate that there are 30 000 ‘illegal miners’ in Gauteng. If you take a dependency ratio of one to eight, you’ve got close to 300 000 people depending on them and if you take them out of the economy, you’re just going to make things worse in Gauteng than they are already.”

Van Wyk says the government should ban any new mining licences along Main Reef Road.

“They should only allow small-scale operations or artisanal operations that are not in close proximity to communities.”

The department of mineral resources and energy claims that capping a mine is rehabilitation, but it’s not, Van Wyk said.

“That concrete slab that they put over the top of a mine is not going to keep anybody out of it. It’s very easy to circumvent it — they actually need to put a plug 25m down into the shaft if they want to keep anybody out.”

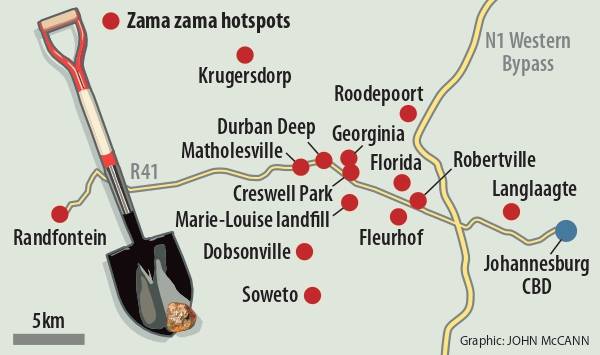

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Every mine site along Main Reef Road from Springs through to Cooke 1 and 2 shafts on the Far West Rand are all squatter camps, he said.

“It’s an indication of the failure of our government to provide housing. It’s a service delivery failure and the only available land is these old mine sites.”

Although there has been some improvement in Riverlea, Mark Kayter, the chairperson of the Riverlea Mining Forum, doesn’t expect it to last long.

“In a month or two, it will go back to the normal situation we had,” he said.

“I don’t even think that we have the resources to fight these guys, we don’t have the manpower or the technology. These guys saw an opportunity, they exploited it and they took full advantage of it. Now, it’s a festering cancer that will take years to heal.”