Egypt’s movements in the Horn of Africa, both diplomatic and military, over the past two years have drawn the attention of observers of Egyptian foreign policy, as well as those following the impact of the developments in the region on freedom of navigation in and international trade through the Red Sea. The wider concerns regarding the future of peace and stability in the region come amid reports of emerging coordination between the Al-Shabaab terrorist movement in Somalia and the Houthi group in Yemen, a development that portends complex risks and exacerbates the nature of security threats facing the region.

Moreover, and by examining the map of the Horn of Africa, one can hardly miss the natural geographical connection with the region further to the west housing the sources of the Nile River. Standing on the natural and strategic linkage between the Horn of Africa and two of the most important axes of Egyptian national security, namely the Red Sea and the Nile River Basin, provides a sufficient explanation for Egypt’s recent intensive diplomatic activity, which has drawn the attention of, and perhaps several questions from, regional and international actors. From this standpoint, it has become necessary to shed more light on the various dimensions of Egyptian interests in the Horn of Africa, which some mistakenly consider new, sudden and driven either by momentary developments in the region or by tactical motives that might serve Egyptian higher and more strategic interests.

It is established that Egypt’s affiliation with the Horn of Africa dates back to ancient history. From the times of Queen Hatshepsut’s, the commercial, cultural, and civilizational ties grew stronger extending through the eras of colonization, decolonization, and Egypt’s support for liberation and independence movements across Africa. From Somalia to Djibouti, and then to Eritrea, the contours of the bonds between Egypt and the peoples and governments of the Horn of Africa were forged leaving a lasting imprint on the cultural and social fabric of a new generation in those countries.

Undoubtedly, the collapse of the regime of Somali President Siad Barre in 1991, and Somalia’s subsequent descent into a vicious cycle of turmoil, followed by the penetration of extremist and terrorist groups seeking to seize control of the country’s resources, constituted a watershed moment in the modern history of the Horn of Africa. These developments compelled Somalia’s neighboring countries to opt for extending their presence on Somali territories, including through sustained military presence. Such presence generated new dynamics on the Somali political and military scene, preventing Somalis from restoring unity of purpose and regenerating a sense of belonging to a common homeland encompassing the country’s various clans, tribes, and communities.

The factors of fragility afflicting the Horn of Africa are not limited to the Somali situation. From the war between Eritrea and Ethiopia, to Ethiopia’s civil war with the Tigray region, the region is continuously challenged by the inherent inclination by certain parties from within to export their chronic internal instability by fabricating external threats, inventing enemies and fueling hostilities resulting from hegemonic tendencies.

Perhaps the latest of these destabilizing ventures in the Horn of Africa has been Ethiopia’s illegitimate attempts, and vocal expression of intention, to secure a naval military presence on the Red Sea coasts, despite being a landlocked state. This, obviously, constitutes a flagrant threat to undermine the unity, territorial integrity, and sovereignty of the states of the region.

In addition, the ongoing Sudanese crisis, which has entered its third year without much prospect for a political settlement or for alleviating the humanitarian suffering of the brotherly Sudanese people, has serious repercussions for the security and stability of the Horn of Africa, particularly as the ongoing conflict invites external ambitions over Sudan’s wealth, its coasts, and its Red Sea ports, with the threat of turning the country into an open arena for regional conflicts.

To complete the picture, it should be noted that the serious Houthi attacks on freedom of navigation in the Red Sea following the Israeli aggression on the Gaza Strip have awakened long-standing and latent plans to secure the maritime passage, involving arrangements that seek to engage regional actors from non-coastal countries of the Red Sea. In practice, the Houthi attacks have triggered militarization in the Red Sea, thus exacerbating threats to the security, safety, and stability of the Horn of Africa, and foreshadowing an escalation of competition, conflicts, and attempts to reshape the geographic and political realities of the region.

From this perspective, Egypt faces a naturally turbulent geographic and strategic extension, rife with conflicts, hostile tendencies, and diverse threats to its national security, making mere observation, monitoring, or reliance on traditional diplomatic methods in managing Egyptian relations with the region’s actors—collectively or individually—a luxury it can no longer afford. It is important to note, in this context, that the countries of the region, which share deep historical, cultural, and political ties with Egypt, view the new Egyptian diplomatic assertive activism as an urgent necessity to deter provocations and manifestations of aggression and delusion of power engulfing the region.

Accordingly, the institutions and agencies of the Egyptian state, both governmental and non-governmental, recognize the need to act along parallel and integrated tracks in order to restore a degree of strategic balance in the Horn of Africa.

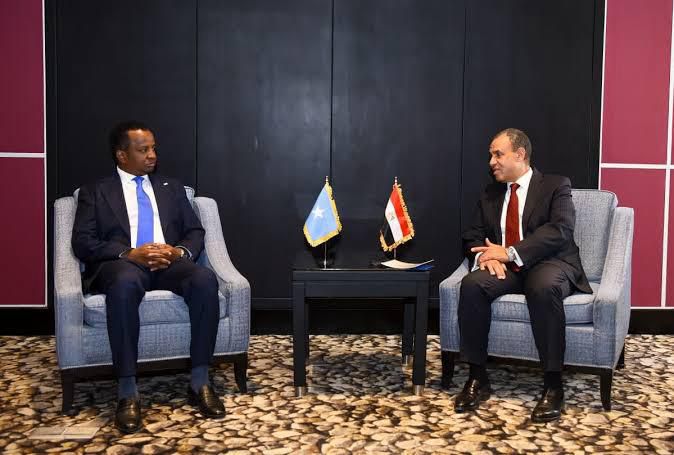

Perhaps the most prominent feature of the renewed Egyptian approach toward the future of the Horn of Africa is its positive response to a Somali request to contribute military and police forces, along with an air component, to the new African Union Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). In addition to the qualitative value that the anticipated Egyptian contribution would add to the African Union’s longstanding peacekeeping efforts in Somalia, this contribution represents the first of its kind for Egypt in the African Union peace support operations, nearly thirty years since Egypt’s contributions to the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Somalia (UNOSOM). This makes the impending contribution to AUSSOM an important indicator of Egypt’s renewed recognition of its role in and responsibilities towards the Horn of Africa. In addition, Egypt has reenergized its economic and cultural relations with, and has intensified its technical and capacity development support for Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya and Somalia. Critical sectors such as energy, infrastructure and education are only examples of a burgeoning multidimensional relations with the countries of the region.

Egypt is of the view that the Horn of Africa does, in fact, possess the necessary drivers of stability and development. Yet, the region is in critical need for a partner who is capable and willing to transfer the required expertise for nation and state-building, while ensuring that the interests of the peoples and societies of the states are well served and prioritized. President Abdel Fatah El-Sisi has pledged that Egypt will deploy all the tools of its renowned diplomacy to restore balance and stability to the Horn of Africa, and to enter into genuine, multi-dimensional and strategic partnerships with the countries and peoples of the Horn of Africa. Consequently, Egypt is set to confidently move to the forefront of the strategic scene in the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea.