The backstreets of Koudougou after rain. Photo: Sean Christie

The N14 between Ouagadougou and Koudougou is busy, especially on the outskirts of Burkina Faso’s capital. Heading westwards between Koudougou and Dédougou, the road becomes eerily quiet. Beyond Dédougou, in the direction of Nouna and the Malian border, it is empty, save for the occasional striding farmer, a hoe over each shoulder, the handles crossing at the chest.

The shadow of three massacres in 2022, at Bourasso (22 killed), Namissiguima (12 killed) and Nouna (at least 28 killed), lies over the area. Although the situation has improved, there are ongoing attacks: a farmer was killed in the road recently, says guide Kiawara Serges Telesphore, who advises that it would be sensible to remain in the central parts of the Boucle de Mouhoun region, of which Dédougou is the capital. To work here we need permission from the province’s high commissioner. It is a public holiday, however, and government offices are shut. After making several phone calls, Telesphore beams.

“The chef de canton will see us,” he says.

The authority of customary leaders is widely recognised in Burkina Faso and in early 2025 it was enshrined in the country’s laws. Albert Lombo Dayo, Dédougou’s Chef de Canton, is responsible for 42 villages. His home is down the road from gare melon, which is empty at the moment, watermelons being out of season. He sits on a throne, resplendent in a silver and white boubou made of Faso Dan Fani, Burkina’s famous hand-woven fabric. Shoes come off, we bow low, take seats off to one side. We are here to speak about the weather, having heard that many of his subjects — farmers, in the main — have experienced a tyranny of floods in recent years.

“It is true.”

He speaks quietly in Bwamu. A man to his right translates into French and another into English.

Since assuming the chieftaincy in 2004, Dayo has received an increasing number of flooding reports from his “chefs de village”.

“We have always had these heavy rains between May and August. I used to pick fish up off flooded pathways as a child,” Dayo recalls, although he insists that farmers’ fields seldom flooded.

Flooded field, alongside Burkina Faso’s Mouhoun River, also known as the Black Volta. Photo: Sean Christie

Flooded field, alongside Burkina Faso’s Mouhoun River, also known as the Black Volta. Photo: Sean Christie

The widespread flooding is a recent phenomenon, he insists, and it is not simply a consequence of increased rainfall or storm intensity but perhaps more the consequence of changes in the way the land is used.

“There are more farmers, so more trees are poisoned and cut down to open new fields. There is nothing to slow the journey of water. The rivers become full, the low areas flood,” he says, adding that a greater number of people farm where they should not — at the edges of rivers and ponds.

Dayo’s take is broadly supported by available meteorological data, which shows that statistically there had been no change in the amount of annual rainfall in Burkina Faso since the 1960s, yet the number of flooding events has increased in the 2000s. There has been bigger rainfall variability, in other words, changes in when the rain comes and how much of it comes at once. This, researchers say, is probably made worse by land erosion affecting run-off.

Dayo is both an ardent traditionalist — the head of the region’s supreme council of traditional chiefs — and worldly, having served in Burkina Faso’s military for 39 years. His sub-text is clear: if you are looking for a straightforward story about climate change and its impacts, look deeper. With that, we have the royal blessing to approach farmers directly.

Albert Lombo Dayo, Dédougou’s Chef de Canton (authority of customary leaders). Photo: Sean Christie

Albert Lombo Dayo, Dédougou’s Chef de Canton (authority of customary leaders). Photo: Sean Christie

Maize, rice and massacres

Our first stop is a farm outside Moudasso village, through which a small river runs. A church complex on the property was abandoned after the Bourasso massacre, which was claimed by the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. On the evening of 3 July 2022, armed men on motorbikes lined up villagers in front of the church on a Sunday night and shot them.

“We have not seen those men again,” says the farmer, Coulibaly Alain, who insists that there is a high degree of religious tolerance in the area and hopes the Christians will return.

A mission station in Boucle du Mouhoun, abandoned after a series of Islamic State attacks near the village of Moudasso in 2022.

A mission station in Boucle du Mouhoun, abandoned after a series of Islamic State attacks near the village of Moudasso in 2022.

A week of rain has made mousse of his farm’s tracks. The river has broken its banks and the fields are partly under water. We remove our shoes, roll up our trouser legs and wade into a maize field. Alain expects to lose 30% of his maize crop. The same thing happened the year before.

Further along, surrounded by low, grass-like plants, Alain says: “For years this was my most productive maize field. Now I plant rice instead.”

The input costs for rice are lower but the risk is higher.

“With maize I knew what I could get, with rice I have no idea, it is very new,” he says. Alain has also planted mangoes — “they like water” — but it will be years before they mature. Until then, he hopes to make ends meet with a combination of the old and the new.

“It is stressful; some nights I don’t sleep,” he says, and in the same breath invites us to join him for a meal of “savage chicken”.

“Guineafowl,” Telesphore whispers.

Alain is more fortunate than most — he is a traditional leader, with other sources of income.

The inundation

Konaté Issouf from Goni village lost 100% of his millet, maize and cotton crops to flooding between August and September 2022, a total of seven hectares. In 2023, a nearby river burst its banks and flooded his home. He and his family evacuated at 2am, in water up to their knees. He lost his home, his millet crop and all his chickens and goats. In the aftermath of the disasters, he made traditional bricks for a living, earning 2 000 West African Francs (CFA) (about R60) for a palette of 20 — not nearly enough to provide for his six children, so he sold two cows, almost all his remaining wealth. Whenever his children asked for food, he panicked.

“I was very impacted, talking alone sometimes like a foolish man. My body was shaking,” he says.

Konaté Issouf, a farmer from Goni village in Burkina Faso’s Boucle du Mouhoun region. Photo: Sean Christie

Konaté Issouf, a farmer from Goni village in Burkina Faso’s Boucle du Mouhoun region. Photo: Sean Christie

Issouf planted rice in 2024 and it has been a steep learning curve. In the past, agricultural extension officers would come out to share information on maize, millet and cotton farming. But nobody has visited since the military junta, led by Ibrahim Traore, took power in September 2022 and so he and his neighbours, who are also new at it, meet to discuss rice farming techniques.

Soft-spoken, almost inaudible, Dakyo Evelyne, was also flooded out of her home in Kansara village in 2023, although she was able to move back in a week later. The problem was that the “inundation”, as she calls it, delayed planting and her family missed their growing season. Like many families in her area, she and her husband have historically had access to other fields further away from the village, which could have been used instead but the threat of attacks prevented them from accessing this land. Like so many of their neighbours they are trying rice.

“We can support our children now but if there is any healthcare problem, I don’t know what we will do,” she worries.

Dakyo Evelyne, a farmer from Kansara village near Burkina Faso’s border with Mali, has started rice farming. Photo: Sean Christie

Dakyo Evelyne, a farmer from Kansara village near Burkina Faso’s border with Mali, has started rice farming. Photo: Sean Christie

Twenty-seven-year-old Yaya Yoba, his jeans patched with gloriously bright fabric, lost more than his crops when floodwaters swamped his fields and home near Nouna in 2024. He and his wife loaded their possessions onto a cart and made for higher ground. Yoba’s 18-year-old brother, Honoré, turned back for his bicycle and was later found drowned, possibly after suffering a seizure.

“I will never forget it,” he says.

Yaya Yoba lost his crops, his home and his brother, who was found drowned by floodwaters in 2024. Photo: Sean Christie

Yaya Yoba lost his crops, his home and his brother, who was found drowned by floodwaters in 2024. Photo: Sean Christie

Coulibaly Perpetue, also from Kansara village, insists that the women in her village have been more impacted by the floods than the men. She and her husband lost 4ha of millet to flooding in 2024. Without millet, she was unable to make traditional millet beer, a business that contributed the largest share of household income.

“One litre sells for 200 francs (about R6) and I can sell 40 litres a day,” she says, not without pride.

In the absence of this income, her husband goes out in search of firewood to sell.

“He has to walk far to find it and he can only do two trips a day, returning with a single bundle each time, which he sells for 1 000 francs (about R30).”

Coulibaly Perpetue lost her millet crop in 2024, which meant she couldn’t make traditional beer, her family’s most lucrative prospect. Photo: Sean Christie

Coulibaly Perpetue lost her millet crop in 2024, which meant she couldn’t make traditional beer, her family’s most lucrative prospect. Photo: Sean Christie

The young men need to plant

We hear variations of the same story wherever we stop: a combination of flooding and extended dry periods is forcing farmers to experiment with new crops or take menial jobs after crop failures, while underlying it all is the persistent threat of attacks. Precarious times, in other words, and farming families in this western corner of Burkina Faso are struggling. A 2020 study drawing on the views of subsistence farmers in Burkina Faso found they rely heavily on a single rainy season for crop production and income generation. When crop sales are poor or non-existent, education and healthcare become unaffordable.

“It isn’t only Dédougou and Nouna — farmers have these challenges across the country and the wider region,” says Dr Ali Sié, who runs the nearby Nouna Health Research Centre.

Sié knows a thing or two about the impact of heavy weather on people’s health. A study he was involved in demonstrated a link between extreme heat and mortality from noncommunicable diseases (NCD) such as diabetes, heart disease and certain psychiatric conditions in rural Burkina Faso. The research found that when maximum daily temperatures reach 41.7°C, the chance of premature death from NCDs rises significantly because heat adds extra stress to stressed bodies. It led Sié and his research partners to wonder what impact extreme weather was having on people’s minds.

“The challenge we face is an absence of data,” he says, adding that there have been no major studies looking at the burden of mental health disorders in Burkinabe farming communities.

Farmers’ mental health has attracted an increasing amount of academic attention in recent years but much of the activity has focused on commercial farmers living and working in North America, Australia and Europe, where research has shown that farmers face a much higher suicide risk than other citizens.

“There has been comparatively little research into the mental health of small-scale farmers, particularly on the African continent. Some studies have been done in neighbouring Ghana in recent years. Although there will be commonalities among people living in different West African countries and elsewhere, there will also be differences and what interventions are possible or suitable may very much depend on those differences,” says Sié.

A flooded farm on the outskirts of Dédougou, where farmers are turning to rice. Photo: Sean Christie

A flooded farm on the outskirts of Dédougou, where farmers are turning to rice. Photo: Sean Christie

Much of Sié’s work in Nouna is focused on better understanding the lives, challenges and coping strategies of farming families. He is working on a survey of 15 000 households, all of them farming families, which is strongly weighted towards mental health. Separately, he is a principal investigator in a multicountry project called Weather Events and Mental Health Analysis*, which aims to highlight the impact of extreme weather events on the mental health of vulnerable groups of people in four African countries, including Burkina Faso.

“For now, we say we know nothing. We know nothing about the prevalence of mental health disorders [in the farming areas of Burkina Faso] or the types of disorders that are affecting people and the causes of those disorders. We expect to learn a lot,” Sié says. Lowering his voice, he confides that some notable trends are emerging.

“Of the more than 7 000 households surveyed to date, we see that more than 30% lived elsewhere three years ago. That is an extraordinary figure if you think about it. These are families that are battling unpredictable weather, battling fluctuating market prices and food insecurity. In addition to this, many of them have been forced from their homes recently. It is a lot to cope with,” says Sié.

For the foreseeable future, rural Burkinabes struggling with poor mental health must cope in the absence of government support. Psychiatrist Désiré Nanema, who advises Sié’s projects, says psychological services remain centralised in the academic hospital in Ouagadougou, where the focus is on severe mental health conditions, such as schizophrenia, while a government programme that aims to shift the responsibility of mental healthcare to specialised nurses is on pause, due to funding issues.

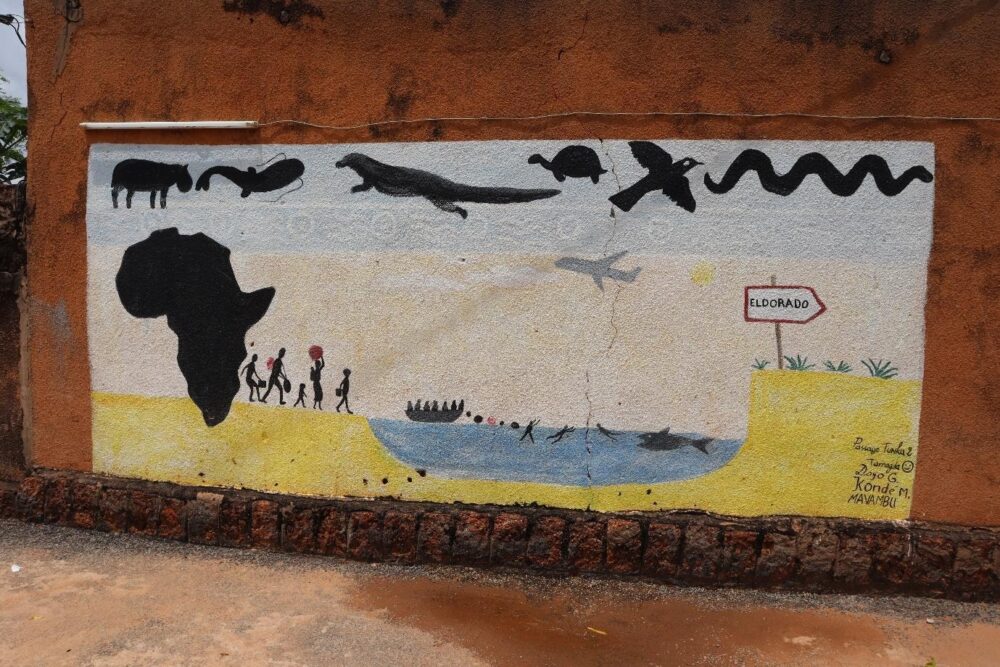

A Dédougou mural depicts Burkinabes taking to the sea in search of “El Dorado”, the mythical golden city. Photo: Sean Christie

A Dédougou mural depicts Burkinabes taking to the sea in search of “El Dorado”, the mythical golden city. Photo: Sean Christie

“In much of Burkina Faso, family is the first rescue in times of crisis. You have these multigenerational households and people come and go, depending on their needs. If a home is flooded, family will offer a room. If a crop is lost, family provides food. You typically do not see camps in Burkina Faso, unless there has been a major disaster and entire family networks are affected,” he says.

Politeness requires that we return to the home of the chef de canton, to debrief and bid farewell. We enter his compound, passing a mural depicting desperate Burkinabes taking to the high seas in search of “El Dorado”, the mythical golden city. We pass some terrifying Bwa statuary, painted green. It is late afternoon and the mercury has pushed into the upper thirties.

“It is getting hotter. Incontestablement,” he says, switching to French. The country’s updated National Adaptation Plan shows a temperature increase of 0.3°C per decade for the region. Dry spells between storms might also be lengthening, he says, all of which makes farming more difficult but the real problem is the clearance of trees.

Dayo gives an order and his self-declared chef de protocol disappears around a corner and returns with a “cailcedra” (African Mahogany) sapling, the last of several thousand distributed to village chiefs for planting during a national tree planting festival in August.

“The young men need to plant,” he says. “That is our solution.”

* This is the third in our series of articles about the impact of climate change on mental health. Read the previous stories here: first, second. Also view our Health Beat TV programme on the mental health impact of floods in KwaZulu-Natal. Bhekisisa is a collaborator on a Wellcome Trust-funded project, which the Africa Health Research Institute at the University of KwaZulu-Natal is leading. Bhekisisa, however, operates editorially independent of the project.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.