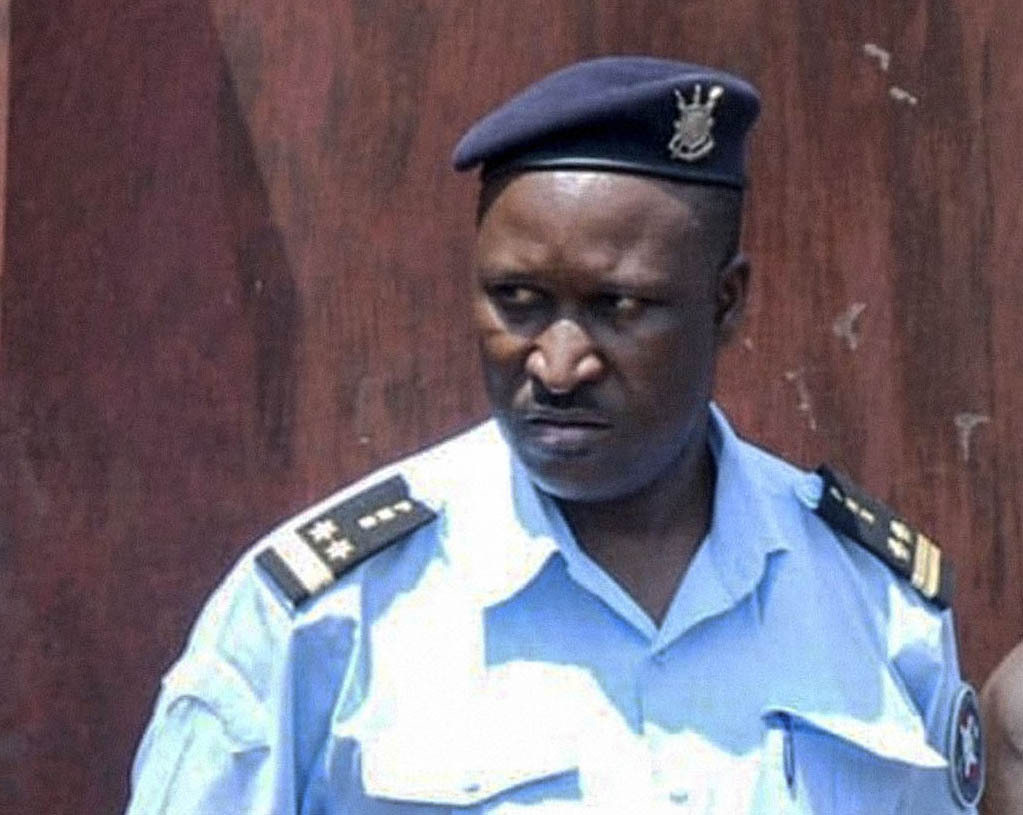

Burundi’s leading independent newspaper Iwacu once asked if Gervais Ndirakobuca wasn’t simply an “untouchable suspect”. (Jennifer Huxta/AFP via Getty Images)

COMMENT

When Gervais Ndirakobuca, the recently appointed Burundi’s security minister, emerged from the bush in 2003, his nickname “Ndakugarika” (which means “I will kill you” in Kirundi) suggested a penchant for violence when he was a rebel commander. But it is his deeds since the end of the civil war that cemented the full cruelty behind his moniker.

Police Commissioner Chief (lieutenant-general equivalent) Ndirakobuca is more like a deputy prime minister in the newly minted cabinet of President Evariste Ndayishimiye. His portfolio fused three giant ministries from president Pierre Nkurunziza’s era. General Ndirakobuca (he is usually addressed as general) is in charge of the interior, security, and community development. Some have speculated that departments from the former ministry of decentralisation will also fall under his bailiwick. He is a super minister.

Gervais Ndirakobuca, the recently appointed Burundi’s security minister.

Gervais Ndirakobuca, the recently appointed Burundi’s security minister.

Ndirakobuca holds another infamous distinction — he is the most internationally sanctioned member of Ndayishimiye’s government. The European Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Switzerland sanctioned Ndirakobuca for serious human rights violations during the bloody repression of the popular movement that protested against Nkurunziza’s quest for a controversial third term as president.

Other senior police and intelligence officials were sanctioned for similar grave violations, but none by as many countries as Ndirakobuca.

Sanctions against Ndirakobuca were also more detailed and specific about his abuses. For example, the EU accused him of “acts of violence, acts of repression and violations of international human rights law against protesters … on 26, 27 and 28 April in the Nyakabiga and Musaga districts in Bujumbura”. The US sanctions cited witnesses who described how “Ndirakobuca shot a civilian in Bujumbura’s Musaga neighborhood” in early June 2015.

The repression went on for months and at least 1 700 lives were cut short. The International Criminal Court has opened an investigation into serious crimes allegedly committed by state agents such as Ndirakobuca.

Perhaps it is the brazenness with which Ndirakobuca acted in 2015 that explains why his rap sheet is specific in its details. On May 20, 2015, French journalist Gérard Grizbec, who was reporting from Burundi tweeted Ndirakobuca’s stern warning to AFP and France2 reporters: “Leave or we will shoot you with protesters.”

That was a serious threat and Ndirakobuca’s threats are not to be taken lightly. In 2010, a formal complaint that a police officer, Jackson Ndikuriyo, had written denouncing serious corruption in the national police surfaced. Ndikuriyo told his lawyer that he began receiving threats from Ndirakobuca, who was at the time the national police’s deputy director general. On August 26 of that year, police agents picked up Ndikuriyo and executed him. The US Department of State and Human Rights Watch reported on this extrajudicial killing.

The former vice-president of Burundi’s Constitutional Court, Sylvère Nimpagaritse, understood the serious nature of Ndirakobuca’s threats. Shortly before midnight on April 30, 2015, he received an insults-laced, threatening call from Ndirakobuca. Earlier that day, the court had debated the constitutionality of Nkurunziza’s third term. The majority of the judges, including Nimpagaritse, had argued a third term would violate both the 2015 Constitution and the 2000 Arusha Peace Accord from which the Constitution derived.

Nkurunziza was losing in court and the streets had rejected him. Ndirakobuca took it upon himself to reverse what would have been the court’s verdict. When Nimpagaritse recognised the voice on the other side of the telephone as Ndirakobuca’s, he knew he had to choose between life and death. Days later, he and his family fled Burundi so dramatically his diary befits a thriller novel.

The judge and his family escaped Ndirakobuca’s claws. Many others weren’t so lucky.

On the morning of April 9, 2009, the tortured and bloodied body of Ernest Manirumva was found in front of his house. Prior to his death, Manirumva served as the vice-president of Olucome, an anti-graft organisation, and was investigating thousands of assault weapons bought by the national police and illegally transferred to rebel groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo — facts a United Nations report later confirmed.

Manirumva is said to have been picked up at this home in the evening of April 8, 2009 and taken to his office, where he was tortured while his abductors searched for files before returning his inanimate body in the early hours the following day.

The national and international uproar that followed the murder of Manirumva led Nkurunziza to accept assistance from the US’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Both the FBI and a national commission of investigation concluded that senior security services’ officials needed to be questioned abot the murder. In July 2010, the FBI requested DNA samples from Ndirakobuca, who was then the deputy director general of police and who had become one of the key suspects in the murder. The FBI also asked that the entire unit under Ndirakobuca’s direct command be investigated.

Ndirakobuca was never questioned and the Nkurunziza regime refused to hand over his DNA samples. Instead, Ndirakobuca’s personal driver and a police agent, Sylvestre Niyoyankunze, who was suspected of driving the vehicle that transported the body of Manirumva back to his home, was, months later, shot several times in the chest in a bar, left for dead and subsequently disappeared from his hospital bed. Niyoyankunze was one of several police agents who worked as drivers or personal security detail to senior security officials suspected in the murder of Manirumva who were later mysteriously killed or disappeared. They knew too much.

The murder of Manirumwa was not the only serious crime where Ndirakobuca was a key suspect. Suspects in the September 18, 2011 Gatumba (Western Burundi) killings, in which 37 people died in a crowded bar, cited Ndirakobuca as one of the masterminds. Although Ndirakobuca is known to have been present in Gatumba that fateful evening, he was never summoned despite lawyers’ insistence at the suspects’ trial. Observers decried a miscarriage of justice.

Since 2015, enforced disappearances have become one of the most sinister aspects of the political crisis Burundi endured. Ndondeza (Kirundi for “help me search”), a civil society-led investigative campaign, has documented hundreds of disappearances and demonstrated the prominent role of Burundi’s intelligence services — the very services Ndirakobuca most recently directed – in these cases.

One case in particular – that of Hugo Haramategeko – points to a possible Ndirakobuca’s direct involvement. According to Ndondeza’s findings, Haramategeko, president of an opposition party, was abducted by armed police agents on March 9, 2016 and driven away in Ndirakobuca’s official vehicle. Haramategeko has not been seen since.

In its oral briefing on July 14 this year, the UN commission of inquiry on Burundi noted that whatever goodwill could be expected of Burundi’s new president, Ndayishimiye, his policies will be implemented by Nkurunziza’s loyalists, some of whom are under international sanctions for grave human rights violations. Ndirakobuca is chief among those loyalists.

Nkurunziza, who died suddenly in June, had shielded Ndirakobuca from investigation, prosecution or accountability for the many crimes he is suspected to have committed or masterminded, Burundi’s leading independent newspaper Iwacu once asked if Ndirakobuca wasn’t simply an “untouchable suspect”. The new president, Ndayishimiye, promoted him.

The International Criminal Court may be the only hope left for following up on Ndirakobuca’s long, bloody trail.