In the living room of their Nairobi home, with children’s toys strewn over the floor, Boniface Mwangi’s young daughter asks him: “Where are you going?”

As he walks out the door, the award-winning photojournalist, activist and politician tells her: “I’m going to topple the government.”

Softie is not exactly what it says on the poster. It’s meant to be a film that documents Boniface’s audacious 2017 bid to run for parliamentary office, as an independent, in his Starehe constituency. It is that: we see him leading protests, getting arrested, handing out flyers on public buses and repeatedly declining – looking a little more crestfallen each time – to hand out cash to demanding voters. His rival has no such qualms.

This is a compelling look at the inner workings of an independent political campaign, and it’s just as fraught as you would imagine: the scene where campaign manager Khadija Mohamed tells an unnamed caller, with a smile on her face, that her husband will “literally crush your balls and then cut them and feed them to the dogs” is a highlight.

But this is not really a film about politics. It’s about love, and family, and the extraordinary personal sacrifice that it takes to fight a system that is designed to crush you.

In their car, on the way to yet another campaign event, Boniface and his wife Njeri Mwangi are talking about priorities. She tells him: “I have given my eldest, and my youngest, and my middle one, my life. So maybe now you give your children your life. Then, after that, you can give the country what is left. Instead of giving your children what is left.”

Boniface replies: “Country comes first, because when you fight for your country, your kids benefit.”

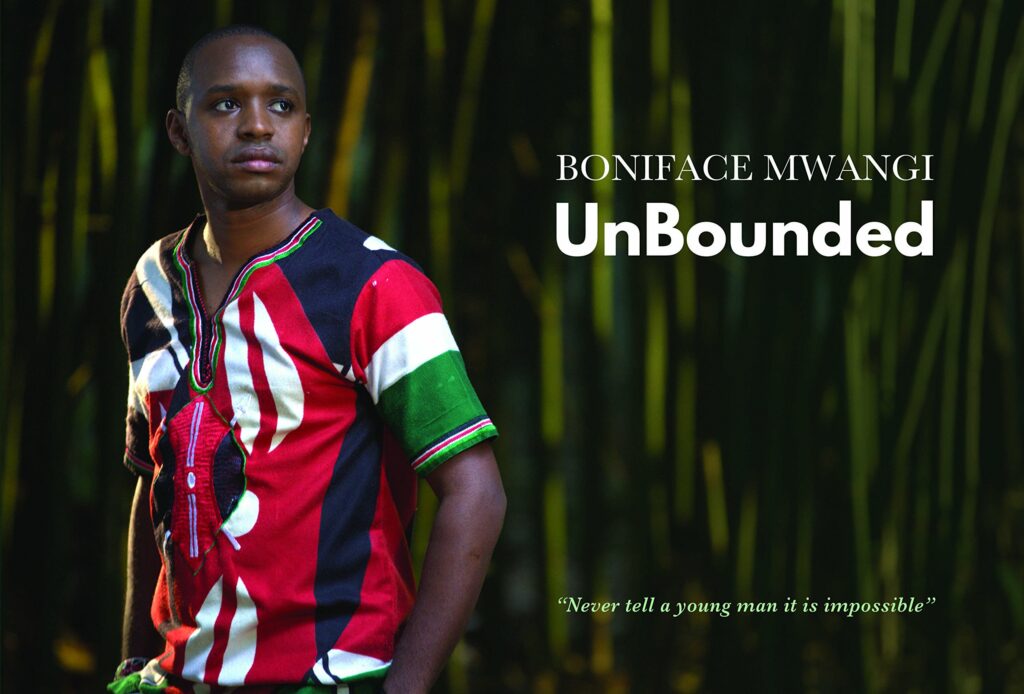

Not long afterwards, at the launch of Boniface’s book, Unbounded, someone slips a letter to Njeri. It’s a death threat. She and the children go into exile in the United States for eight months, only returning days before the vote. Boniface keeps campaigning, and the video calls between husband and wife grow more and more strained.

“I don’t want to die,” Boniface explains, “but if I die and it changes a few things …”

Njeri interrupts. “But what if it doesn’t?”

A life of activism puts an immense pressure on personal relationships, and often creates both emotional and physical distances between loved ones. Zimbabwean activist Evan Mawarire’s family also went into exile in the US, for their own safety. Angolan investigative journalist Rafael Marques de Morais was denied a visa to visit his son in Canada because he was facing “criminal charges” at home – even though these charges were trumped up by an authoritarian regime, to silence him.

For Njeri Mwangi – who, for all Boniface’s abundant charisma, is the real star of this show – there is no adulation or awards to compensate for, or even to recognise, her sacrifice. “I don’t struggle with being a mother. Being Boni’s wife, that’s hard. Because then I am his wife. People don’t see me for me. They don’t know me. It’s like I don’t have my dreams, my ambitions.”

As the election draws near, Boniface and his team are filmed setting out for a rally on a fleet of branded yellow motorcycles, weaving at dusk through Nairobi traffic as Sauti Sol’s Tujiangalie provides a suitable epic soundtrack. This is the drama, the grand theatre, that makes Kenyan politics – all politics – so compelling, and in Softie there’s no shortage of it.

But the film’s genius lies in the quiet moments; in the compelling intimacy of a young couple trying to reconcile raising a family, and living their ideals, even as the world seems to conspire against them.

Softie will be screened at the Durban Film Festival and the Encounters Film Festival, ahead of a US premiere on October 12. It was directed by Sam Soko and produced by Soko and Toni Kamau. After winning the World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award for Editing at the Sundance Film Festival, it is now eligible for Oscars consideration.

This review first appeared in The Continent, the new pan-African weekly newspaper designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Get your free copy here.