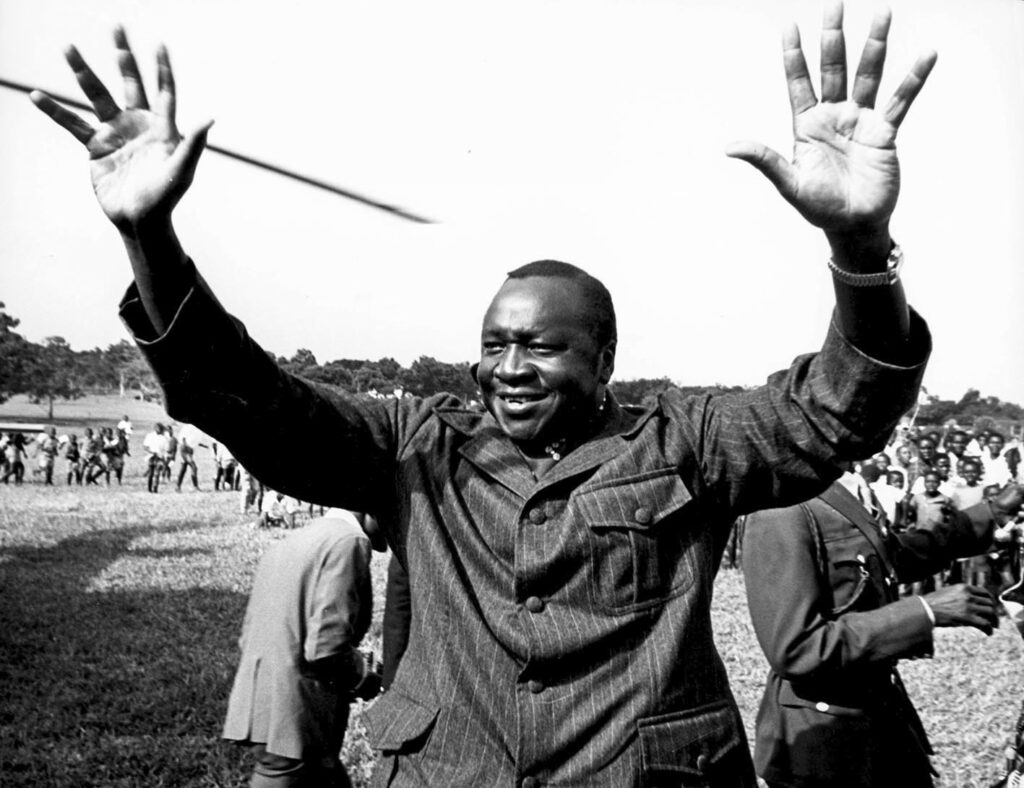

The British mistakenly believed Idi Amin would be their puppet after he overthrew the socialist Milton Obote. He soon proved to be eccentric, unpredictable and uncompromising.

COMMENT

Perhaps no African leader has generated as much intrigue as Idi Amin Dada, the self-styled conqueror of the British Empire and Ugandan dictator. He was cruel, but not uniquely so. How did he earn infamous status in the horrible dictators’ Hall of Fame?

Amin has featured in at least three films: Mississippi Masala, Entebbe and The Last King of Scotland (which won an Oscar). He was portrayed as a crazed and unfathomable man. He persists in popular culture well beyond his native Uganda nearly two decades after his demise.

I was born shortly after the collapse of his regime. I travelled widely in Uganda, lived and studied in the United Kingdom and worked in West Africa and, during this time, I met many different versions of Amin.

As a child I remember him as a comical character. If you spoke broken English, you would be the subject of endless ridicule and labelled Amin. It did not help that his nickname was Chikito (“big shoe” in Runyankole, the language spoken in southwestern Uganda) on account of his big feet. This is the caricature we children knew him to be.

In secondary school, I grew to understand Amin as a dictator with no hesitation to kill. The memory of the funny, oafish and big-footed dancer quickly faded. I would learn from my older siblings of the “random” disappearances in our area under his reign. It soon became clear that he was not the same person we joked about as children. Claims of Amin’s cannibalism and feasting on his son Moses abounded. Although dubious, these were the stories Hollywood would later seize on.

When I moved to Europe, I met other Amins. He put Uganda on the map for London’s average Joe, courtesy of West-centric films and documentaries. Six out of 10 times, Amin’s name pops up in the first minute of conversation when I mention I am from Uganda. “Oh wow … Idi Amin!” Those who had not heard of Uganda knew about Amin; it was almost as if he was Uganda.

What is often forgotten about the man is the ideology that rationalised his most notorious actions: “Africanisation”, a disastrous quest to undo colonial economic inequalities that was also embodied by his contemporary, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe.

After mixing with wealthy, educated children in London, I started meeting Amin sympathisers — some daring to interrogate the historical amnesia surrounding colonisation and “the empire”. Often, many were happy to ignore Amin’s bloodthirsty paranoia in favour of his ideology.

But Amin was himself a creation of empire. The British mistakenly believed he would be their puppet after he overthrew the socialist Milton Obote. He soon proved to be eccentric, unpredictable and uncompromising.

What made Amin a joke for us when we were children, made him fantastic fodder for Hollywood. The stereotype of a paranoid African ruler pervaded mainstream films primarily aimed at a white audience. But he was naturally eccentric, larger than life and, in all honesty, kind of funny.

Yoweri Museveni’s government cannot afford to miss out on Amin’s memory — and cashing in on his infamy. An Idi Amin museum is being planned after the exhibition of The Unseen Archive of Idi Amin, first at the Uganda Museum and then at other centres. It features 200 photographs drawn from about 70 000 negatives of previously unseen photos dating from the 1950s to 1980s that were found in 2015 at the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation.

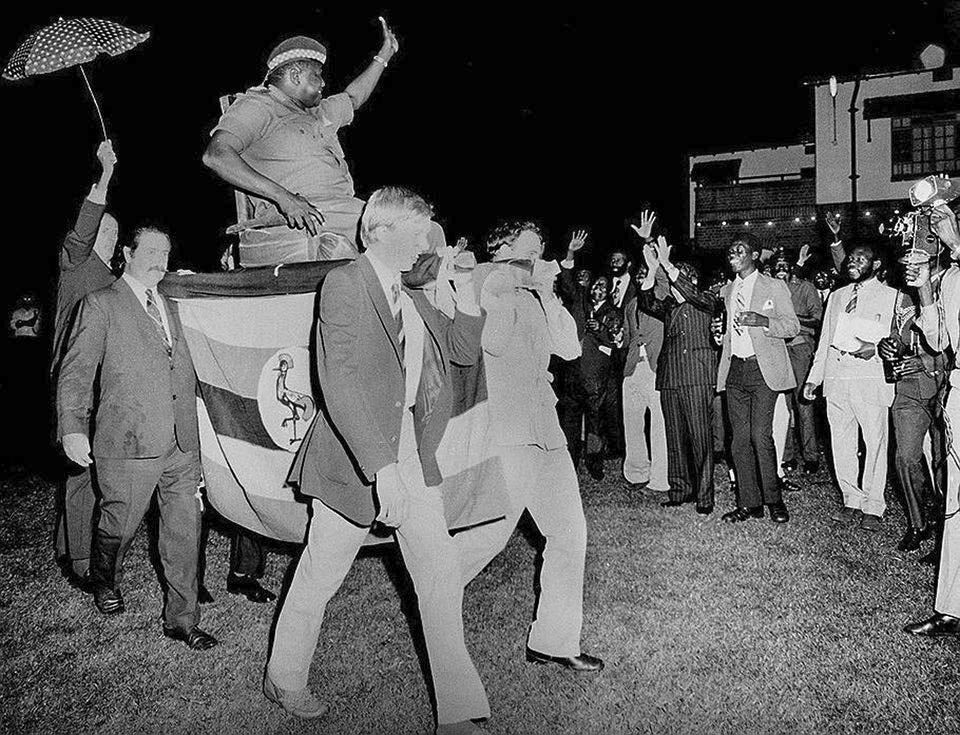

In short, we have a character who is vilified by the West yet loved by Hollywood; a comic character for children in Uganda but lauded by the Arab world for “standing with his Muslim brothers” after allowing a plane hijacked by Palestinians to land at Entebbe airport.

Amin made and followed his own rules. He was not simply a politician. While others, such as Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, played politics to their personal advantage, Amin was unique in his poor grasp of the political realm, his unrealistic optimism and the terrible means he used to achieve his ends.

Even 50 years later, this makes it difficult to accurately define his place in history.