Yoruba Star: Gbemisola Isimi shamed Timbuktu Global into relinquishing their trademark (Photo: She Leads Africa)

It is not simple to learn Yoruba in London. When Gbemisola Isimi’s first child was born she could find nowhere to teach it the language that she had grown up with in Lagos.

Isimi took matters into her own hands. She started CultureTree, a Yoruba language academy for the children of Nigerian expatriates; and began posting teaching videos on YouTube. In London, home to a sizable Nigerian community, her business took off. One programme, Yoruba Stars, was particularly successful.

Like all smart business owners, she decided to trademark the name ‘Yoruba Stars’ so that no one else could use it. She filed a request with the United Kingdom’s Intellectual Property Office, and waited several months to hear back.

Her request was denied. Another company had already trademarked the word ‘Yoruba’ in Britain, and it had opposed her application. The company said she needed to pay if she wanted to use the word in her business.

Isimi did some research. The company in question, Timbuktu Global, is a clothing company based in the north of England, owned by two white people with no obvious connection to Nigeria or the Yoruba ethnic group. Nor do they appear to have any connection, or even knowledge of, Timbuktu – claiming on their website that the ancient Malian city is “a fictional location which literally means ‘the middle of nowhere’”.

This week, Isimi took to social media to raise the alarm. “I thought it was really strange that a company would be allowed to trademark the word ‘Yoruba’, a tribe and language of millions of people!” she tweeted. “Let’s all call out @timbuktuglobal on this daylight robbery! Today it’s Yoruba, tomorrow it could be Igbo, Swahili or even the word AFRICA! I intend to fight this with everything in me!”

Her tweets went viral. Within days, the flood of negative publicity had forced Timbuktu Global to surrender the trademark and delete their social media accounts and website.

Isimi may have won this battle, but this is not the first time nor last time that intellectual property laws have allowed western individuals or companies to lay claim to Africa’s cultural, linguistic and even culinary heritage.

A few of the most egregious incidents:

- In 2003, in successful patent applications in the Netherlands and the United States, a Dutchman named Jan Roosjen claimed to have ‘invented’ teff flour and all associated food products – including injera, Ethiopia’s staple food, which has been consumed in the Horn of Africa for millennia.

- Rooibos, the herbal tea, is only grown in a very specific area of South Africa – and has done so for hundreds of years. In 1994, an American company registered “Rooibos” as a trademark in the United States – and demanded that South African companies pay them to use the name.

- Following the success of the Lion King, the Walt Disney corporation trademarked an entire Kiswahili phrase: ‘Hakuna Matata’(meaning, as Timon and Pumbaa tell us in the movie, ‘no worries’).

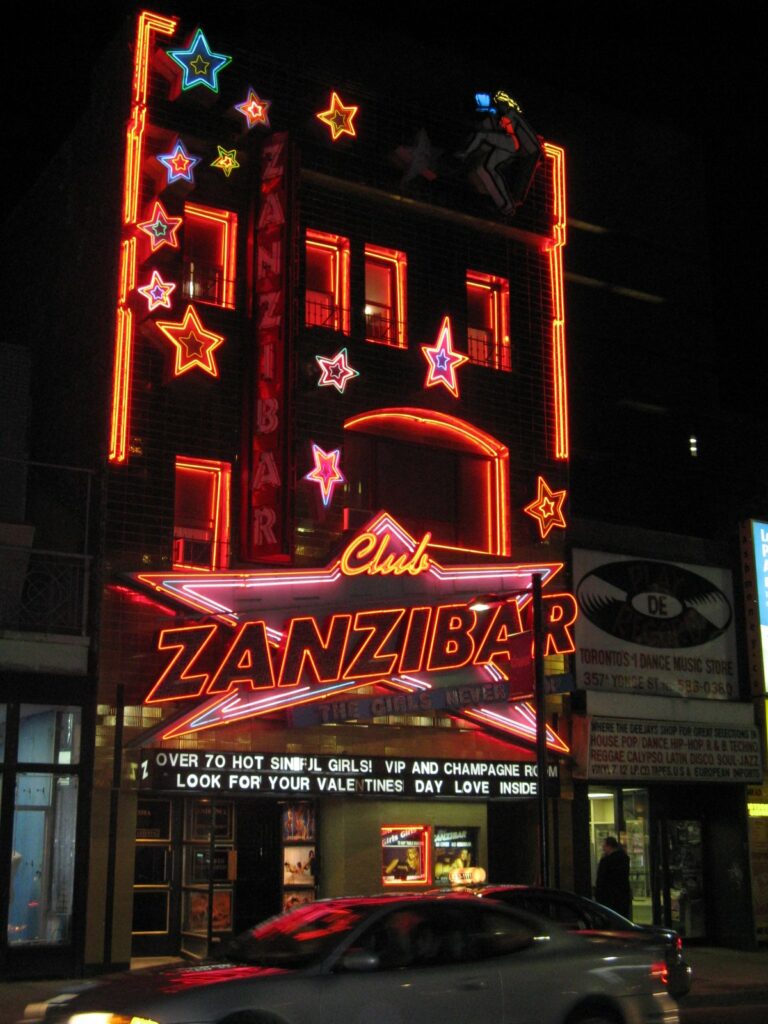

Far from home: The Zanzibar Club is one of Toronto’s oldest strip clubs (Photo: Danielle Scott)

Far from home: The Zanzibar Club is one of Toronto’s oldest strip clubs (Photo: Danielle Scott)

In a quick search of the World Intellectual Property Organisation’s database, The Continent discovered several other examples of western brands which have trademarked African names, symbols and cultural references. Often these associations reinforce negative stereotypes, or simply rely on an African name as a kind of shorthand for ‘exotic’ or ‘other’.

In Canada a trademark for “Zanzibar” is owned by Toronto’s oldest strip club, the Zanzibar Club.

In the United States, the words “Zulu Warrior” are registered to a company that makes a herbal remedy for erectile dysfunction, and whose logo features an image of a scantily-clad soldier clutching a very upright spear.

These examples raise difficult questions about the effectiveness and the fairness of western intellectual property regimes.

For Gbemisola Isimi, the Yoruba trademark scandal highlights a much bigger problem. “Why should we have to spend our time and resources rectifying something that should never have happened?”