A member of the Afar Special Forces stands in front of the debris of a house in the outskirts of the village of Bisober, Tigray Region, Ethiopia.(Photo by EDUARDO SOTERAS / AFP) (Photo by EDUARDO SOTERAS/AFP via Getty Images)

On the afternoon of November 2 last year, Gebremichael Teweldmedhin, a Tigrayan jeweller and father of nine, headed to work in Gonder, a city in the Amhara region of northern Ethiopia where he had lived for more than three decades.

When Gebremichael arrived in the city, he found a mob looting his nephew’s workshop. Gebremichael begged them to stop. Instead, they turned on him.

One relative, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals, told the Bureau of Investigative Journalism: “The looters took them, Gebremichael along with another 10 or 11 people who worked in that area — by vehicle. We tried to follow them but we were not able to get their whereabouts.

“Then other people told us they were killed. They are buried in a mass grave.”

Gebremichael was not political, his relative said. He was not educated, and did not read the hatred and misinformation that swamps Ethiopian social media. Yet his relative claimed online hate campaigns and calls for violence — particularly on Facebook — played a key role in not only his killing, but those of many others.

“The worst thing that contributed to their killing are the so-called activists who have been spreading hate on social media,” he told the Bureau. Some posts, he claimed, would name individuals or even post photos, helping create an atmosphere “inciting attacks, killings and displacements”.

Gebremichael Teweldmedhin

Gebremichael Teweldmedhin

Thousands have died and millions more have been displaced since fighting broke out between government forces and armed opposition groups from the country’s Tigray region in November 2020. The government has also been fighting an armed group from the Oromia region, and the United Nations secretary general António Guterres said last November that “the stability of Ethiopia and the wider region is at stake”.

On November 9, Mercy Ndegwa, Facebook’s public policy director for East Africa, and Mark Smith, its global content management director, used a blog post to offer reassurances that Ethiopia “has been one of our highest priorities” and that their company “will remain in close communication with people on the ground”.

But the Bureau’s investigation has uncovered a litany of failures. The company has known for years that it was helping to directly fuel the growing tensions in the country. Many of those fighting misinformation and hate on the ground — fact checkers, journalists, civil society organisations and human rights activists — say Facebook’s support is still far less than it could and should be.

A senior member of Ethiopia’s media accused Facebook of “just standing by and watching this country fall apart”. Others told the Bureau that they believed requests for assistance had been ignored and that arranged meetings did not take place. These failures, they said, were helping to fuel a conflict that has already led to reports of ethnic cleansing and mass rape. Amnesty International has accused both sides in the conflict of carrying out atrocities against civilians.

Yet posts inciting violence or making false claims designed to encourage hate between ethnic groups in Ethiopia have been allowed to circulate freely. The Bureau has identified and spoken to relatives of people allegedly killed in many attacks, but has not been able to cross-check specific details on the ground because of the ongoing violence.

Facebook said it had worked for two years on a comprehensive strategy to keep people in Ethiopia safe on their platforms, including working with civil society groups, fact checking organisations and forming a special policy unit.

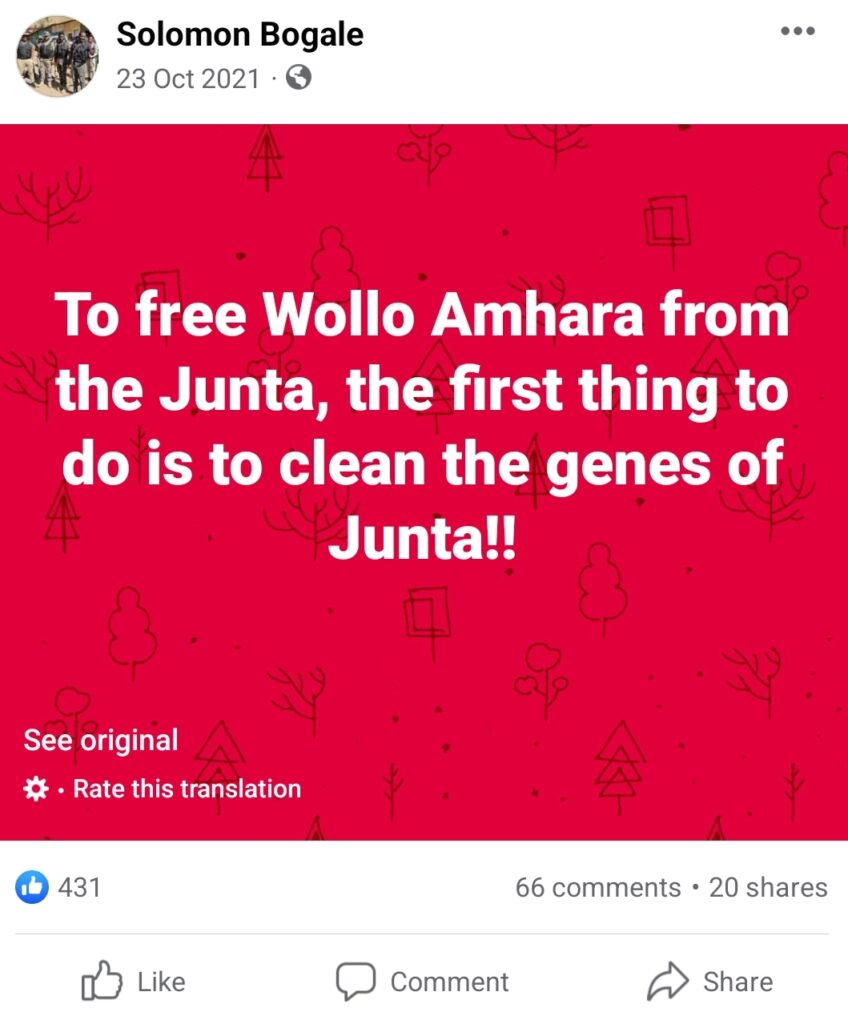

Gebremichael’s family cited one Facebook user in particular: Solomon Bogale, an online activist with more than 86 000 followers on Facebook. Though listed on Facebook as living in London, Bogale’s social media indicates that he has been in Ethiopia since August 2021, with posts of him in fatigues and carrying an assault rifle often accompanied by statements praising the Fano, an Amharan nationalist vigilante group.

One of Gebremichael’s family members said Bogale’s “inciteful posts” had resulted in many attacks on Tigrayans in Gonder.

In the weeks before Gebremichael’s killing, Bogale called for people to “cleanse” the Amhara territories of the “junta”, a term often used by government supporters to refer to the Tigrayan forces fighting the government and to Tigrayans more generally. The post continued: “We need to cleanse the region of the junta lineage present prior to the war!!”

On October 31, two days before Gebremichael’s disappearance, Bogale posted an image of an older women holding grenades, with the caption: “#Dear people of Amhara, there are mothers like these who are fighting to destroy Amhara and destroy Ethiopia! The main solution to save the #Amhara people and to protect Ethiopia is we Amharas have to rise up!! Get together Amhara.”

The Bureau has verified that both posts remained on Facebook almost four months later, along with many others from various sources containing hate speech, calls for violence and false claims. Throughout the conflict misinformation and hate have been used on Facebook and other social media, inflaming tensions and influencing the outcome of military operations.

Contacted through Facebook, Bogale denied that any Tigrayans were killed in Gonder in early November, saying all Tigrayans in the city were safe. He claimed that Tigrayan forces had killed ethnic Amharans in the region.

He also said he would delete the posts cited by the Bureau.

Facebook said it had reviewed the posts flagged by the Bureau and had removed any content that violated its policies. The Bureau found one post had been removed. At the time of publication, the post of the woman holding grenades remained online.

Criticism of Facebook’s failings is made more damning by the extensive evidence that the company has known of the risk of such problems for years, according to disclosures made to the US Securities and Exchange Commission and provided to the US Congress in redacted form by the legal counsel of Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen. The redacted versions received by Congress were reviewed by a consortium of news organisations, including the Bureau.

As early as January 2019 an internal report into various countries’ “On-FB Badness” — a measure of harmful content on the platform, including hate and graphic violence — rated the situation in Ethiopia as “severe”, its second-highest category.

By June 2020, Facebook had become even more starkly aware of the problem. An internal document discussing measures used to assess the level of harmful content said it had “found significant gaps in our coverage (especially in Myanmar and Ethiopia)”.

Six months later, Ethiopia had risen to the top of Facebook’s list of countries where it needed to take action. In a presentation circulated on 10 December 2020, the risk of societal violence in Ethiopia was ranked as “dire” — Facebook’s highest threat warning. It was the only country to be given that ranking.

More than a year later, the Bureau’s investigation has found that Facebook is said to have frequently ignored requests for support from fact checkers based in the country and some civil society organisations say they have not had a meeting with the company in 18 months. The Bureau has learned from multiple sources that Facebook only appointed its first senior policy executive from Ethiopia to work on East Africa in September.

Facebook does run a third-party fact-checking programme, providing partners with access to internal tools and payment for fact checks. As its website states: “We rely on independent fact checkers to review and rate the accuracy of stories through original reporting.” But it has not partnered with a single organisation based in Ethiopia to tackle the misinformation spread by all sides in the country’s conflict.

Abel Wabella, founder of the Ethiopian fact-checking initiative HaqCheck, said Facebook had failed to support his organisation since he first approached executives more than a year ago.

“They told me, ‘Okay, we can help you, just write to us, our email.’ They gave me their cards. And I wrote to them,” he told the Bureau. But he heard nothing back. “At that time, our initiative was very small, so I thought they didn’t find something good in our platform, so they wanted to keep silent because of that.”

Wabella sent two further emails over the next few months, the second to the new Facebook executive from Ethiopia he had heard had been appointed. Despite assuring him that she would take action in September, he said he had heard nothing from the company since.

Rehobot Ayalew, HaqCheck’s lead fact checker, said the lack of support had severely hampered her team’s work. “Most of the people have low media literacy, so Facebook is considered to be credible … So working with Facebook, and also checking and verifying Facebook content, is the major way to counter this disinformation.”

Wabella added: “The problem is not specific to Tigray. Ethiopian citizens from every corner across ethnic groups were severely affected by hateful content circulating online, specifically Facebook.”

The other major independent fact-checking organisation based in Ethiopia, Ethiopia Check, is also not part of Facebook’s partner programme.

Facebook said it had constantly worked with civil society organisations and human rights groups on the ground, but did not partner with HaqCheck and Ethiopia Check because neither was certified by the International Fact-Checking Network.

Facebook does work with two fact-checking organisations on content from Ethiopia — PesaCheck, which runs a small team in Nairobi, and Agence France-Presse — but both of them are based outside the country. AFP has just one fact checker in the country. Although misinformation flagged by PesaCheck and AFP has often been labelled as false or removed by Facebook, content investigated and debunked by HaqCheck has largely remained unaltered and free to spread.

This has included false declarations of military victories on both sides, false allegations of attacks on civilians and false claims of captured infiltrators. On November 25 last year, the Ethiopian government banned all unofficial reporting of battles, further enforcing an information vacuum in which misinformation spreads easily.

“As far as I know, support for fact checkers in Ethiopia by Facebook is almost non-existent,” said the senior person working in Ethiopian media, who asked to remain anonymous. “Facebook doesn’t pay the attention Ethiopia needs at this crucial moment, and that’s contributing to the ongoing crisis by inflaming hatred and spreading hate speech.”

A number of civil society groups have similar complaints of feeling ignored and sidelined. Facebook organised a meeting with several groups in June 2020, to discuss how the platform could best regulate content before scheduled elections. As of November, two of the organisations involved said they had heard nothing about any subsequent meetings.

“The recent development has been overwhelming. Facebook should have had a similar consultation,” said Yared Hailemariam, executive director of the Ethiopian Human Right Defenders Centre. “Facebook also ought to have a working group, collaborating with human rights organisations and civil society groups.”

Haben Fecadu, a human rights activist who has worked in Ethiopia, said the hate speech issue was flagged to Facebook years ago but the company had still not provided adequate resources to deal with it.

“There’s really no excuse and I wish someone had come down harder on them about it,” she said. “I’ve doubted they have invested enough in their Africa content moderation, and doubt that the Africa team has had enough resources to moderate content properly. They don’t have enough moderators … I suspect they didn’t have a Tigrinya-speaking moderator until very recently.”

Facebook’s owner, Meta, said in January that it would “assess the feasibility” of complying with a recommendation by its independent oversight board that it launch a human rights assessment of its activity in Ethiopia. The recommendation came after the board directed Facebook to remove a post that claimed Tigrayans were involved in atrocities in the Amhara region.

Ayalew, the HaqCheck fact checker, said the inadequate support from one of the world’s richest companies was demoralising. “We usually come across sensitive content, images that are horrifying and hateful content. It’s hard by itself,” she said. “And when you know that, even though you’re trying, you’re not getting the support from the platform itself, that is allowing this kind of content.

“You ask yourself why? Why am I doing this? Because you know that they can do more, and they can change the situation. They have a big role in this, and they’re not doing anything. You’re trying alone.”

Mercy Ndegwa, speaking on behalf of Facebook, said: “For more than two years, we’ve invested in safety and security measures in Ethiopia, adding more staff with local expertise and building our capacity to catch hateful and inflammatory content in the most widely spoken languages, including Amharic, Oromo, Somali and Tigrinya. As the situation has escalated, we’ve put additional measures in place and are continuing to monitor activity on our platform, identify issues as they emerge, and quickly remove any content that breaks our rules.”

Just over three weeks after Gebremichael’s murder, Hadush Gebrekirstos, a 45-year-old who lived in Addis Ababa, was arbitrarily detained by police who heard him speaking Tigrinya.

Hadush Gebrekirstos

Hadush Gebrekirstos

“After they knew he was a Tigrinya speaker, they said, ‘This one is mercenary’ and took him to a nearby police station … They were beating him hard,” said a relative, who also wished to remain anonymous and who was told what happened by witnesses.

“Two days after — on November 26 — his body was found dead, about 200 to 150m from the police station. They threw his body out there.”

Again, Hadush’s relative said he had no political or social media engagement. Again, he believes that it was lies and hate on Facebook that played a key role in causing the killing.

“It really does. Irrespective of reality, because people do not have the ability to verify what was posted on Facebook. Like calling people to kill Tigrinya speaking residents — as a result of hatred and revenge feelings … You don’t even know who is killing you, who is detaining you and who is looting your property. It’s total lawlessness.” — Bureau of Investigative Journalism