Welcome: A man walks to the Namugongo Catholic shrine in Uganda.

Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church, visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan last week. His visit renewed focus on the growing role of African Catholics within the church more broadly.

Africa is home to nearly 20% of the world’s Catholics — 236 million of the 1.36 billion Catholics worldwide. And the church is growing faster here than it is anywhere else in the world. Recent statistics show that it grew 2.1% between 2019 and 2020, compared to just 0.3% in Europe.

A large proportion of Catholics in Africa are young people — the continent’s median age is around 19. This is in contrast to the trend in many other parts of the world, where young people leave the church because they think it is too staid and conservative.

The pope will want, especially, to encourage African youth to take more of a role in shaping the future of the church and society in their respective nations — and perhaps encourage them to support his own reform agenda, which is not especially popular on the continent.

Although large, enthusiastic crowds greeted Francis in Kinshasa and Juba, many Catholics will hold views contrary to his progressive vision. Many Catholic dioceses and institutions in Africa embrace a more conservative style of Catholicism in their doctrines and rituals.

African bishops will agree with Francis on several issues he often addresses — poverty, care of the environment, social injustice, corruption and war.

However, many of these prelates will also push back and stand firm against Francis’s progressive stance on divorce and remarriage, for example.

It is no secret that many African Catholic leaders have not embraced Pope Francis’s style, vision and reform agenda. This is especially clear when it comes to issues like homosexuality, clerical privilege, church structure and the role of women in the church.

Some leaders, such as Archbishop Alek Banda of Lusaka, Zambia, recently supported the ongoing criminalisation of his country’s LGBTIQ community. Many young priests being ordained from African seminaries would hold to a much more conservative theology. They would be suspicious of the “liberation theology” that is closely identified with Francis’s papacy.

The decline in young men entering seminaries in the northern hemisphere means that many of the world’s Catholic priests will soon be of African descent. This fact alone is changing the face of global Catholicism from a church of the north, with European missionaries, to a church of the south made up mainly of missionaries from regions like Africa.

People in Kinshasha greet Pope Francis on his recent visit to Democratic Republic of the Congo

People in Kinshasha greet Pope Francis on his recent visit to Democratic Republic of the Congo

This will not only shape global Catholicism in the years to come, but it will also give African Catholics considerable influence to shape the church’s future.

Francis has often spoken about the African church being given more of a voice in the church and in the world. He has visited the continent at an important moment in the history of global Catholicism, when he seeks to listen more closely to those on the margins.

In 2021, he embarked upon an ambitious global consultation in the Catholic Church called “The Synod on Synodality”.

Francis is asking the whole church to enter the dialogue and to speak about anything that needs to be addressed. He has reiterated that anything can be spoken about in the process, which is expected to end next year.

He is hoping to hold dialogues with African Catholics specifically, even though several issues that have already been put on the table globally — such as women in ministry, compulsory celibacy for clergy and homosexuality — have been frowned upon by African Catholics.

Unfortunately, in some places on the continent, there has been little done by local leadership to engage in this process. They disagree with the pope’s approach, characterised by dialogue.

Francis is also visiting a church divided by cultures, languages and ethnicities. A tragic example of this is the ongoing conflict in Cameroon between the mostly French-speaking government and rebels in English-speaking areas, which has claimed thousands of lives.

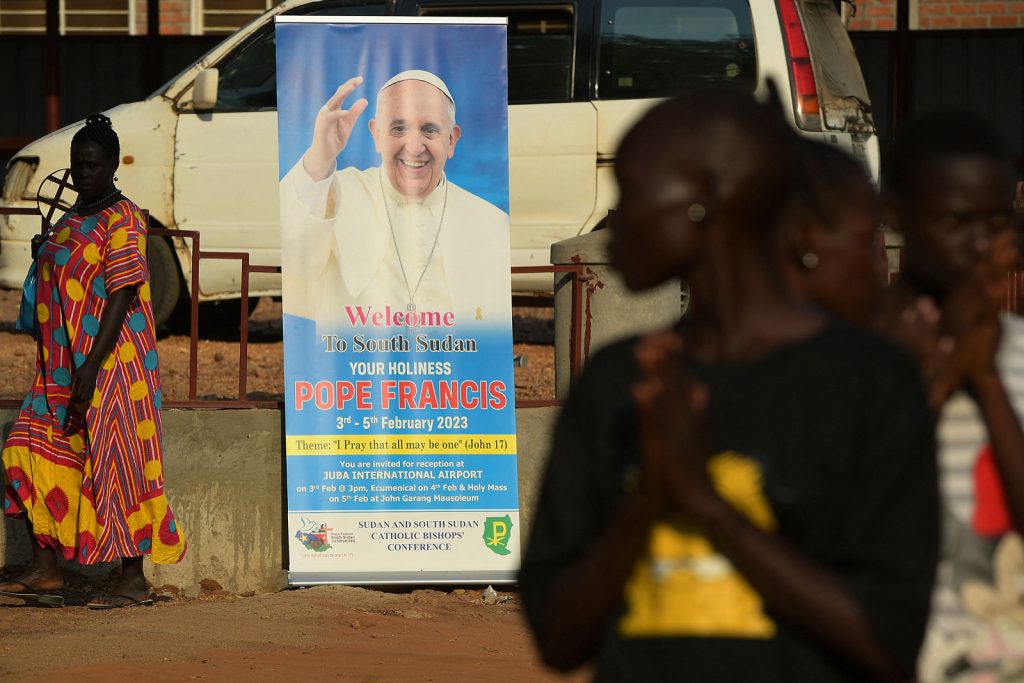

Preparations for his visit to South Sudan

Preparations for his visit to South Sudan

Leaders in the Catholic church are divided and unable to speak with one voice as they, too, are rooted in the country’s colonial history.

Francis hopes that young people can play an increasingly active role in addressing many of the conflicts and widespread poverty on the continent. In the DRC last week, the pope told Catholics to be a “conscience for peace” and to “break the cycle of violence”.

The church often plays an essential role in addressing societal issues. For example, the Catholic bishops in the DRC and Nigeria organised a successful protest against violence. In addition, the Rome-based Catholic organisation Sant’Egidio brokered peace in Mozambique, ending the civil war in 1992.

In many countries, the church also fills in for the state where dysfunctional and corrupt governments have failed to provide for their people.

For example, the highest number of Catholic health facilities on the continent (2 185) is in the DRC. This is followed by Kenya (1 092) and Nigeria (524).

Francis urged young people in the DRC to resist greed and corruption, criticising politicians who have embezzled millions and personally profited from several countries’ natural resources. He encouraged young people to choose a future different from the past.

In Kinshasa, this call was immediately picked up by the crowd, who started to call for an end to the rule of President Felix Tshisekedi, a president whose contested election victory was not recognised by the church.

This is the pope’s fifth visit to Africa in 10 years, underscoring how important he views the continent to be.

Given the exponential growth of African Catholicism, it is not much of a stretch to wonder, could the next pope be African?

This article first appeared in The Continent, the pan-African weekly newspaper produced in partnership with the Mail & Guardian. It’s designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Download your free copy here.