Coup: Nigeriens hold a sign reading ‘Together we will make it’ during a march called by supporters of coup leader General Omar Tchianis. Photo: Djibo Issifou/Getty Images

Nigeria, leader of a key West African bloc and a continental economic powerhouse, has intensified its efforts to reverse the coup in neighbouring Niger, presenting Abuja with opportunities as well as risks.

The Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), chaired by Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu, said on Sunday that coup leaders had a week to restore Mohamed Bazoum to Niger’s presidency after he was toppled by his presidential guard.

But Ecowas took many by surprise when it threatened the possible “use of force” to restore constitutional order.

“It’s time for action,” Tinubu said.

Nigeria’s chief of staff, Christopher Musa, echoed the commander-in-chief, warning in an interview on RFI Hausa radio that if ordered, his forces were ready to intervene.

Burkina Faso and Mali, both led by military officers after coups, have warned that military intervention in Niger to restore Bazoum would be seen “as a declaration of war” against them.

Resolving the crisis is a “survival test” for regional leaders, said Confidence MacHarry, a security expert at Nigeria’s SBM Intelligence.

“If the plotters are allowed to get away with it, other countries will live under the shadow of coups,” he said.

Tinubu lived through three decades of military dictatorship before Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999 and is critical of a coup in a neighbouring country.

As Africa’s most populous country with 215 million people, Nigeria probably wants to regain its status as a regional player as well as preventing issues on its soil.

“Nigeria would have the most to fear from Niger’s destabilisation as it shares a 1 600km border that Nigerian security forces are too overstretched to properly secure,” said James Barnett, a researcher at the Hudson Institute in Washington.

Tinubu said he feared a spillover of jihadist groups into Niger and an influx of refugees.

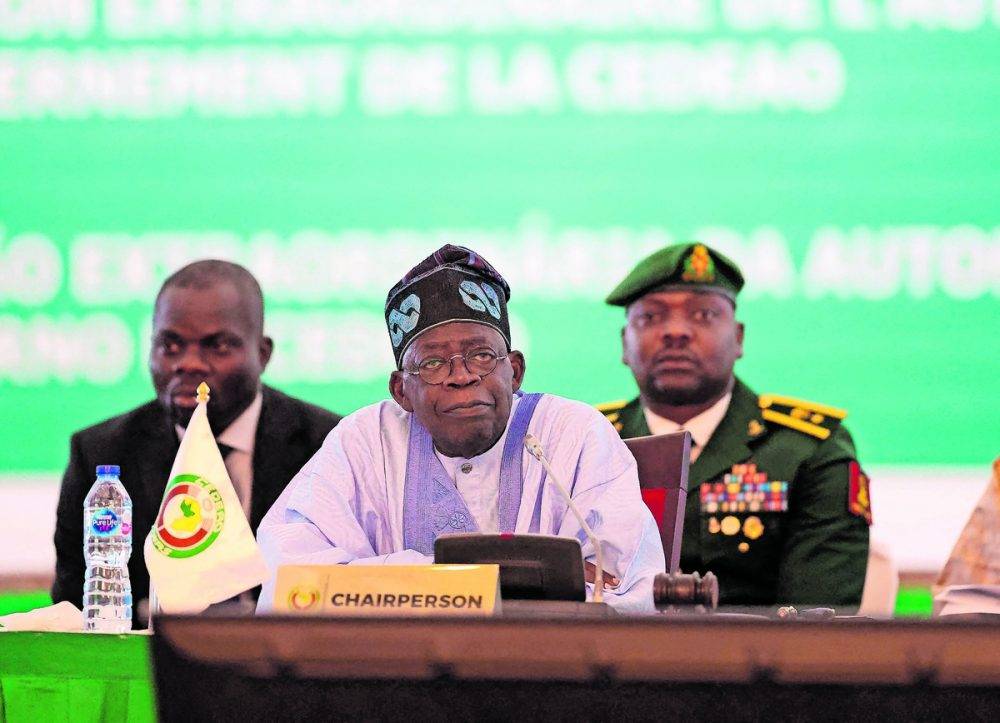

Chair of the Economic Community of West African States and Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu has criticised Niger’s regime

change. Photo: Kola Sulaimon/Getty Images

Chair of the Economic Community of West African States and Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu has criticised Niger’s regime

change. Photo: Kola Sulaimon/Getty Images

Nigeria is already facing widespread insecurity, including criminal gangs in the centre and northwest, jihadist groups in the northeast and separatist unrest in the southeast.

The multiple fronts are straining the Nigerian army, one of the largest in the region that is underfunded and under-equipped, and which is already failing to pacify the homeland.

If there is a military intervention in Niger, “Nigeria would send soldiers. It is normal”, MacHarry said. “But the government doesn’t have the resources for that, [it’s] not prepared.”

Although President Bola Tinubu has made clear his determination to return Nigeria to the diplomatic map, declaring “Nigeria is back”, he still faces challenges at home.

Experts doubt he has the means to fulfil his ambitions at a time when the country is in the grip of a severe economic crisis.

At home, huge social anger is rumbling on, with threats of nationwide strikes and protests.

His first reforms aimed at reviving the economy have caused an inflationary surge in the country where nearly half the population lives in extreme poverty.

Tinubu was elected president of Nigeria in a vote contested by his two main opponents.

Their appeals are still being examined by the courts.

Experts doubt that Nigerian soldiers will even agree to be deployed in Niger, given the strong links between the two armies, which are made up of many Hausa — an ethnic group present across the Sahel.

“It is unthinkable that Nigerian soldiers will go into Niger and fight its soldiers which we see as our brothers,” said a senior military official who asked not to be named.

“It is most likely to be a disastrous outing because the troops will not have the courage to execute the mission.”

Experts are asking whether the threat of intervention itself could resolve the crisis.

Barnett said that if Niger’s military waivers, a return to civilian rule is possible. But if the junta follows through on its threat to rally the population to its cause, “things could get quite ugly”. — AFP