On the front page of its very first edition in June 1985, The Weekly Mail carried an exposé, written by Janet Wilhelm, of how the apartheid security forces were recruiting Mozambican refugees to fight in its destabilising war against the Mozambican government.

Since then, the cornerstone of the paper has been its many investigations into various forms of dishonesty, skulduggery and malfeasance in (usually) high places.

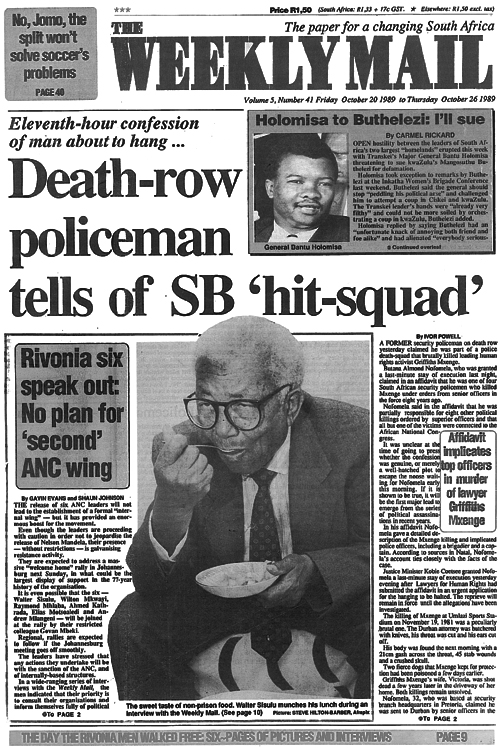

In 1989, The Weekly Mail broke the shattering story of the apartheid state’s death squads. Their existence had long been suspected by activists, so many of their number having been mysteriously murdered, but it was Ivor Powell’s interview with Almond Butana Nofemela that finally cracked through the regime’s denials.

Nofemela was a death-row prisoner who confessed that he had worked for the Vlakplaas unit that carried out such assassinations. His former commander, Dirk Coetzee, then told all to the Mail ‘s fellow “alternative” paper, Vrye Weekblad.

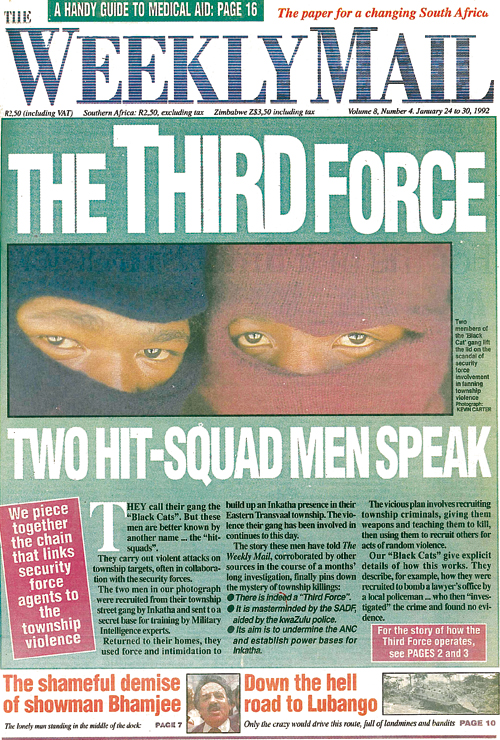

A year later, even as the liberation movement was coming home after the unbannings of February 1990, there was further evidence of the state’s secret war on anti-apartheid activists. This time it took the form of “Third Force” men who had been trained for such activities by Military Intelligence (MI) at a secret base in Namibia.

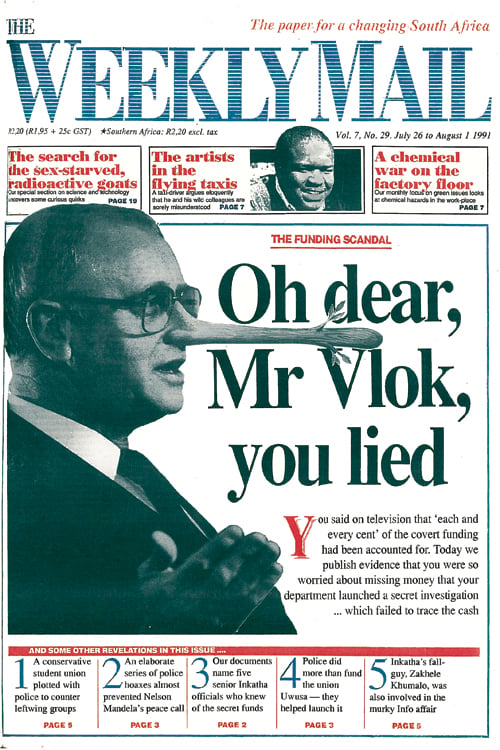

What was called “Inkathagate” really broke in July 1991, when information obtained from a renegade policeman by Guardian correspondent David Beresford showed unequivocally that MI was funding the Zulu-based organisation Inkatha, once anti-apartheid, later the government of the Kwa- Zulu “homeland” and now involved in trying to block the growth of support for the ANC.

On TV, co-editor Anton Harber confronted Adrian Vlok, the then minister of police, with the claims: he denied some, and the paper was then able to show, in the following week and with a famous doctored photograph of Vlok, that he had lied. Further evidence followed soon after.

In 1992, Inkatha Youth League leader Mbongeni Khumalo defected and told his story of Inkatha/MI collaboration to The Weekly Mail. In the same year, Eddie Koch and Philippa Garson revealed that MI and Inkatha had recruited township gangsters to attack ANC sympathisers such as civic organisations calling for rent boycotts.

The Goldstone Commission was established by government to investigate such claims, but even as it sat more evidence of the MI network of “Third Force” operatives, fronts and schemes was uncovered in stories by Drew Forrest, Gavin Evans, Louise Flanagan and others. It included the story of how MI had put Ciskei leader Oupa Gqozo in power.

Yet more details of such activities would emerge in 1995 when Koch and Stefaans Brümmer related former security policeman Paul Erasmus’s confession of “dirty tricks” including the poisoning of Frank Chikane and the bombing of Cosatu House.

The Mail was also fond of sending disguised reporters into situations to find out what was going on. For instance, Koch had posed as an honorary prison warder in 1989, hiring convicts to work on his “farm”, an illegal side-business conducted by warders and farmers, and in 1992 a mere white coat allowed Bafana Khumalo into Baragwanath hospital to report on appalling conditions there.

In other first-person investigations, Fumane Diseko became a child labourer for a day, and Thandeka Gqubule went “back to school” in the township. After 1994, members of the ruling ANC developed complex business relationships that began to look like corrupt practices (when the state wasn’t just being ripped off ).

In 1995 the Mail & Guardian revealed how the head of South Africa’s Central Energy Fund was involved in dodgy oil dealings with the one-time finance minister of Liberia, Emmanuel Shaw II. Shaw sued for R7-million but then fled back to Liberia before the case could be tried.

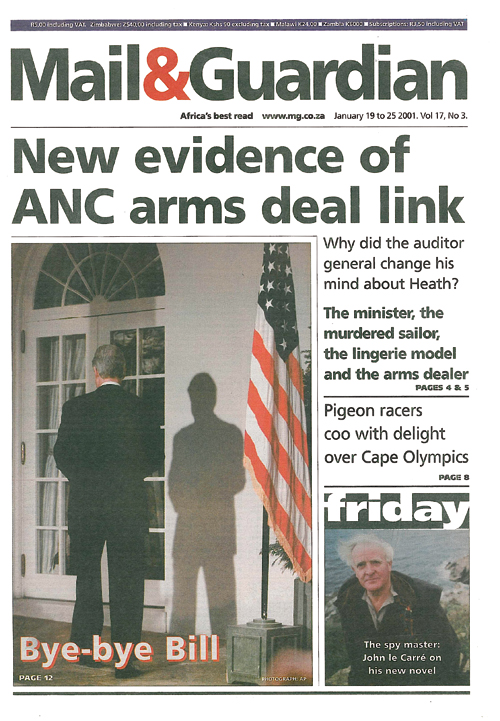

The arms deal concluded by the Thabo Mbeki administration early in his tenure began to show evidence of malfeasance in 2001, and the M&G ran a series of stories exposing it. Sam Sole revealed how Shamin “Chippy” Shaik, head of the defence department’s acquisitions committee, had manipulated tenders, and other stories revealed how defence minister Joe Modise and ANC MP Tony Yengeni benefited from such deals. Yengeni was later jailed, albeit briefly.

In 2003, the M&G revealed how Jacob Zuma, then deputy president, was implicated in crooked arms deals through his “financial adviser” Schabir Shaik, who was paying Zuma’s bills while soliciting bribes in his name.

Oil was again the focus in scandals of 2003 and 2005. The first involved an oil deal between South Africa and Nigeria that resulted in the siphoning of state oil funds into a mysterious Texas company; the second blew the lid on “Oilgate”, in which state oil funds were illegally diverted, through the private Imvume company, to the ANC’s election coffers.

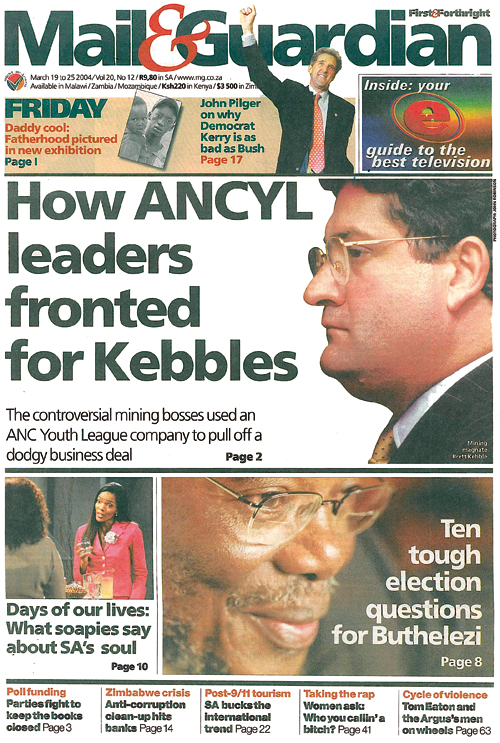

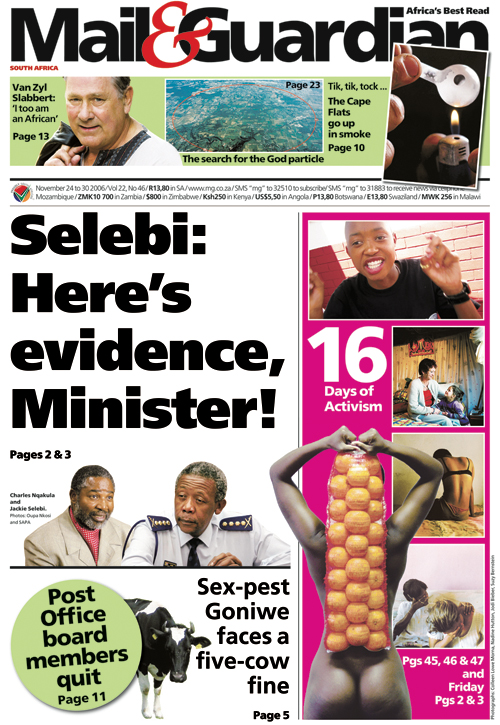

In parallel with the oil exposés, the M&G investigated the shadowy links between crooked mining mogul Brett Kebble and the ANC Youth League’s growing business empire, which he was financing. The story would explode in 2006 when Sole, Brümmer, Zukile Majova and Nic Dawes exposed Kebble’s links to police chief Jackie Selebi.

Despite state denials, a succession of stories on Selebi would ultimately lead to his conviction for corruption in 2010.

In April this year the M&G launched its Centre for Investigative Journalism, a non-profit initiative supported by the Open Society Foundation. The centre was nicknamed amaBhungane, isiZulu for dung beetle — a creature that makes something useful out of manure.