Eating: former driver Collins Foromo & cousin Tshepo Malema.

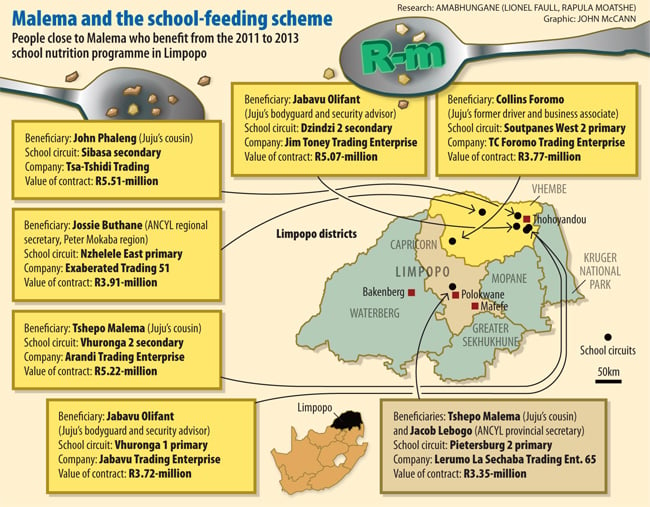

The R1.7-billion school feeding programme in Limpopo appears to have been rigged to favour people close to Julius Malema — allegedly after he presented a list of people he wanted to be cut in. They include two of his cousins, his part-time bodyguard and security adviser, his former driver, his former driver’s girlfriend and two of his close allies in the provincial ANC Youth League. Five sources — two of them senior administrators in the provincial education department at the time — independently told the Mail & Guardian they heard Malema had handed provincial education MEC Dickson Masemola a list of favoured service providers in May 2011, with what one source described as a “political instruction” to ensure they were accommodated. In the feeding frenzy that ensued, the tender scores and specifications were allegedly manipulated and this cohort of Malema’s close associates emerged as beneficiaries.  The seven school nutrition contracts awarded to Malema’s known associates and allies are worth a combined R40-million over two years. Responding to the allegations this week, Malema said: “I never sent any list to the department. Whoever says that I did must produce that list and say ‘at this time and at that place Julius Malema gave the department this list’. I don’t even know anyone who deals with nutrition in the education department.” Malema said that he used to “work closely” with Masemola when he was still ANC Youth League president, but added that “there’s never been a time when we sat down to discuss who gets what tender. Ours was not a relationship about tenders; it was about good leadership and mutual respect.” Department spokesperson Pat Kgomo said Masemola “categorically denies having ever received a list from anybody regarding any tender” and added that the allegation “has all the hallmarks of character assassination”. One of the senior administrators, who spoke to the M&G on condition of anonymity, said that Peter Letsoalo, the senior manager of supply chain management in the department, had told him about the list. Sifting Letsoalo was one of four people who served on the evaluation committees that sifted through tender bidders’ applications. Letsoalo said: “Those rumours are wrong that I teamed up with Julius and the youth league members to formulate such a list. I don’t know these people and I am not a member of the youth league. “I was the secretary of the evaluation bid committee and my work was only to write down minutes, nothing more.” Another bid evaluation committee member, Mokgadi Aphiri, is the department’s senior manager in charge of special projects, which include school nutrition. A well-informed source in the special projects department said Aphiri was a former appointments secretary to Masemola and had been “parachuted in” to the school nutrition programme to ensure the MEC’s directives were obeyed. Already there But Kgomo said that when Masemola became MEC in 2009, Aphiri was already working in his office as one of five officials the previous MEC had appointed. “It cannot be correct that Aphiri’s appointment has anything to do with Masemola,” said Kgomo. He did not clarify why Aphiri was later transferred to the special projects department to oversee school nutrition. Aphiri referred questions to Kgomo. People connected or allegedly connected to Malema who are reflected in departmental documents as having won school nutrition tenders include:

The seven school nutrition contracts awarded to Malema’s known associates and allies are worth a combined R40-million over two years. Responding to the allegations this week, Malema said: “I never sent any list to the department. Whoever says that I did must produce that list and say ‘at this time and at that place Julius Malema gave the department this list’. I don’t even know anyone who deals with nutrition in the education department.” Malema said that he used to “work closely” with Masemola when he was still ANC Youth League president, but added that “there’s never been a time when we sat down to discuss who gets what tender. Ours was not a relationship about tenders; it was about good leadership and mutual respect.” Department spokesperson Pat Kgomo said Masemola “categorically denies having ever received a list from anybody regarding any tender” and added that the allegation “has all the hallmarks of character assassination”. One of the senior administrators, who spoke to the M&G on condition of anonymity, said that Peter Letsoalo, the senior manager of supply chain management in the department, had told him about the list. Sifting Letsoalo was one of four people who served on the evaluation committees that sifted through tender bidders’ applications. Letsoalo said: “Those rumours are wrong that I teamed up with Julius and the youth league members to formulate such a list. I don’t know these people and I am not a member of the youth league. “I was the secretary of the evaluation bid committee and my work was only to write down minutes, nothing more.” Another bid evaluation committee member, Mokgadi Aphiri, is the department’s senior manager in charge of special projects, which include school nutrition. A well-informed source in the special projects department said Aphiri was a former appointments secretary to Masemola and had been “parachuted in” to the school nutrition programme to ensure the MEC’s directives were obeyed. Already there But Kgomo said that when Masemola became MEC in 2009, Aphiri was already working in his office as one of five officials the previous MEC had appointed. “It cannot be correct that Aphiri’s appointment has anything to do with Masemola,” said Kgomo. He did not clarify why Aphiri was later transferred to the special projects department to oversee school nutrition. Aphiri referred questions to Kgomo. People connected or allegedly connected to Malema who are reflected in departmental documents as having won school nutrition tenders include:

- Tshepo Malema, Julius Malema’s cousin, who did not respond to requests for comment. He won the primary school circuit in Seshego, where Julius went to school.

- John Phaleng, who denied that he was Malema’s cousin, despite three sources saying that he is. “I only see him on TV. I think people want to discredit Julius,” he said.

- Collins Foromo, Malema’s driver turned businessperson, who said: “I didn’t get that tender via Julius or Masemola, but on the basis of my capacity as a businessman. I am a businessman in my own right.”

- Foromo confirmed that his girlfriend, whose name is known to the M&G, also won a contract.

- Jabavu Olifant, Malema’s bodyguard and security adviser. Olifant is accused of not delivering food to the school circuit for which he is contracted (see “Delivery of food a hit-and-miss affair” below).

- Jossie Buthane, the youth league’s secretary in the Peter Mokaba region, who refused to comment.

- Jacob Lebogo, the league’s provincial secretary, could not be reached for comment.

Malema said his associates “should not be condemned” for knowing him. “I’ve always told them: ‘Never be afraid to do business with government, but also never expect any favours from me.’ They have a right to be economically active, but they must all comply with the law and if not then they must be charged.” Tender irregularities The education department was one of five placed under administration by the national government in December last year after the province signalled it was under severe financial strain. Critics of Premier Cassel Mathale and Malema, his close ally, believe that allegations of widespread corruption, cronyism and maladministration precipitated the intervention, but their allies maintain that President Jacob Zuma orchestrated it to embarrass and neutralise his political opponents. The Sunday Independent reported recently that the first administrator appointed to the department, Anis Karodia, warned a fact-finding delegation from the National Council of Provinces in March that the school nutrition programme had “collapsed well before the intervention strategy had been put in place”. The M&G understands that Karodia also laid charges against both Masemola and Mathale for allegedly transgressing key provisions in the Public Finance Management Act with regard to the school nutrition programme and allegedly influencing the manner in which the tenders were awarded. Karodia — who resigned after a public spat with Basic Education Minister Angie Motshekga over the textbooks and workbooks that were not delivered to Limpopo schools earlier this year — declined to comment this week. Kgomo said that Masemola had not seen Karodia’s report to the council of provinces and could not comment. Nonsense “However, the MEC would not be in a position to influence the awarding of tenders because he does not sit on any committee which deals with procurement. To make such an unsubstantiated allegation is nonsense.” Mathale’s spokesperson, Mashadi Mathosa, said: “Our office attended the council of provinces meeting earlier this year. However, we are hearing for the first time that the premier is implicated in the report that Dr Karodia tabled. “The premier is not involved in the process of awarding tenders in the provincial departments. Our office has no knowledge of the allegations raised in your questions and we cannot comment on something that we are not aware of.” Damning indictment The M&G has seen a copy of the auditor general’s 2011-2012 audit findings on the department that deal in part with the school nutrition programme. It is a damning indictment of the way the tender process was handled. The auditor found that the department flouted national treasury regulations, stating “the procurement process for … supply and delivery of food staff at schools was not fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective”. It cites four major irregularities, including that:

- Bidders who were not subject to any evaluation were appointed;

- Bidders who were evaluated and scored highly were not appointed;

- Bidders who were evaluated and whose scores were low were appointed; and

- Bidders had to predict the price range within which to bid, or were not appointed.

The M&G has also seen the evaluation scoresheets and other documentation for a significant number of the 7 096 companies that had put in bids for the 733 contracts that were up for grabs. Several requirements were openly flouted. For example, some companies scored more than the maximum 90% weighting for price, which gave them an edge over companies which scored the maximum possible on this key requirement. In addition, many companies were registered less than 12 months before the tender was adjudicated in May 2011, but were selected despite the requirement that they should submit audited 2009-2010 financial statements. Bid evaluation committee reports also show that, after the bids were in, the department decided that a narrow price range of R2.10 and R2.15 per primary school pupil per day and R3.00 and R3.05 per secondary school pupil per day would apply. Bidders who fell outside this range were automatically excluded, even if they were offering a cheaper price. It is noteworthy that Malema’s associates all bid neatly within the prescribed price range. Locality Finally, the tender specified that “preference will also be given to bidders residing within a particular district”, a requirement taken to mean bidders located in the districts where they would deliver food. But service providers from Polokwane and Malema’s nearby hometown of Seshego dominate, most notably in the Vhembe district, where more than half the primary school circuit winners and a third of the secondary school circuit winners are from Polokwane or Seshego and include the bulk of Malema’s associates. These winners appear to have been copied and pasted in exact order from the list of companies who were evaluated for tenders in the Capricorn district (which includes Polokwane and Seshego) to the list of winners from Vhembe. The main towns in Capricorn and Vhembe, Polokwane and Thohoyandou, are 180km apart by road. Kgomo declined to comment on the tender process, saying it was sub judice. The Sunday Independent reported earlier this month that two businesspeople from Vhembe approached the North Gauteng High Court to have the tender award reviewed. Floundered Their case has floundered after the judge ordered that they shoulder the estimated R2-million cost of serving 337 companies with summonses. One of the businesspeople, Mashudu Ligunuba, told the M&G that he had successfully delivered foodstuff to schools in the Vhembe district for the past three consecutive tender rounds. He added that the Vhembe School Feeding Scheme Association, an organisation he founded to co-ordinate the delivery of foodstuff across the district, was now defunct. Ligunuba bemoaned the fact that service providers from faraway Polokwane with no prior school feeding experience had been imposed on Vhembe. He said his profit margins on delivering food to schools used to be 70%. Said Malema: “The emergence of a new layer of young entrepreneurs in Limpopo must be celebrated. I wouldn’t know how those guys [in Vhembe] didn’t get a tender. If they have a problem, they must complain so that a proper investigation must take place.”

Delivery of food a hit-and-miss affair

“When we don’t get food delivered, two-thirds of our pupils go down to town to buy some and don’t come back until the next day,” said a despondent deputy principal at a secondary school in the Bakenberg North circuit, Limpopo, a week before the end-of-year exams. The principal asked not to be named, saying he was not authorised to speak to the media. The school has not received food since the beginning of term three weeks ago and the contractor, Modjadji Mphela, could not explain why. “I won’t be able to answer your questions on the phone, because I still need to get hold of the documents giving reasons why I stopped supplying food to schools,” Mphela said this week. Bakenberg North is one of six circuits in Limpopo the Mail & Guardian visited to see how the national school nutrition -programme was serving schools. Orphans and a bodyguard In Vhuronga 1 circuit, near Thohoyandou in the Vhembe district, a primary school principal said 80% of his pupils were orphans who depended on the nutrition programme for one regular meal a day. This is where Julius Malema’s bodyguard, the beefy Jabavu Olifant, has been contracted to deliver food — but has not done so since April. Olifant said he had not delivered because the department owed him money: “I met the department last week and they promised to resolve the matter very soon.” But the M&G has seen delivery notes and invoices from Olifant’s company for deliveries in August claiming to have delivered food. “The problem is that principals are afraid to report politically-connected suppliers,” said Maurice Petje, principal of Mahlatjane Primary School in Mafefe in Nokotlou circuit in the Capricorn district. Oops Olifant could be in for a shock. After the M&G contacted the department to inform it about the situation in Vhuronga, spokesperson Pat Kgomo said: “We’ve received reports about [Jabavu’s circuit] and we’re busy processing its termination. We’re not aware of the delivery notes, as alleged, hence we’re processing the termination of the contract. Nobody can be paid for not delivering food.” Petje said the programme sometimes fed two generations of pupils from the same families. He estimated that two-thirds of older secondary school pupils in his circuit had young children in the nearby primary schools. Most principals the M&G interviewed said they would prefer to procure their own food rather than rely on service providers from distant Polokwane, Seshego and other urban centres. They said procurement that was driven by schools would boost local employment, shorten supply chains and ensure more oversight and accountability. Rotten Long supply chains mean that schools receive up to a month’s supply of dry foodstuff — including mealie meal, samp, beans, rice and soya — at a time. A week’s supply of fresh food can be problematic because schools lack storage facilities that are sufficiently big, secure against thieves and rats, or cool enough to prevent it from rotting. Kgomo said the department was piloting a procurement system driven by schools. It is being tested by 25 schools. “At the end of the term of the contract we will assess all possibilities and take a decision. But most schools have not indicated discomfort with the present arrangement.”

Limpopo school nutrition by numbers

- R1.71-billion: School nutrition programme budget over two years

- R40-million: Amount earned by known Malema associates and allies over two years

- 1.596-million: Learners in Limpopo receiving food

- 3 931: Primary and secondary schools in Limpopo receiving food

- 7 096: Companies who bid for school nutrition programme tenders

- 337: Companies contracted to deliver food

- 70%: Profit margin of some service providers

- 55%: Percentage of 2012-13 budget spent by September this year

Help us with this investigation

Do you know of other politically connected service providers who have won school nutrition programme tenders in Limpopo? Go to www.mg.co.za/limpopofatcats to see spreadsheets of all 337 service providers and their directors and contact us at [email protected].

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism, a non-profit initiative to develop investigative journalism in the public interest, produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for all our stories, activities and sources of funding.