Cyril Ramaphosa is the poster boy of BEE

A break during which he could wait out soon-to-be president Thabo Mbeki's two terms and return as a "relatively young man".

But now that Ramaphosa has been nominated by several provinces for the ANC deputy president position and could be on the verge of a return to the party leadership, it appears that his years in the empowerment wilderness may have seriously dented his working-class credibility.

Add to this his involvement as a shareholder in Lonmin, the mining company at the heart of the Marikana massacre, and Ramaphosa's political career looks a lot more problematic than it did in the mid-Nineties.

So, who exactly is Ramaphosa, a man worth R3-billion, in 2012 and what does he have to offer the working-class majority of the ANC?

It is clear that the stage is set for a Ramaphosa comeback and it is the anger about ANC deputy president Kgalema Motlanthe potentially running against Jacob Zuma for the ANC presidency that has opened the door for him.

Speculation about Ramaphosa's presence on the Zuma supporters' slates is rife. Some have said that Ramaphosa ingratiated himself with Zuma's supporters while running the process that ensured former ANC Youth League president Julius Malema was kicked out of the ANC.

Heavy-hitter

Others have speculated that the Zuma camp felt that the president needed a heavy-hitter as a deputy because he was going into the electoral conference weaker than he was in Polokwane in 2007.

Ramaphosa's return as a prodigal son of the ANC is likely to raise mixed emotions, although this counts for nothing at the moment because he has not signalled his intention to accept the nomination.

His nomination has become more controversial since emails emerged in the Farlam commission, which is investigating the massacre at Marikana, showing that the day before the massacre Ramaphosa called on the government and police to intervene, calling for "concomitant action" and describing the striking miners as "dastardly criminal".

The dependence on the law to protect business interests that is displayed in the emails stands in stark contrast to Ramaphosa the founder of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in 1982.

In Anthony Butler's 2007 biography, titled Cyril Ramaphosa, the former union boss is characterised as a tireless worker who felt deeply about the exploitation of mine workers.

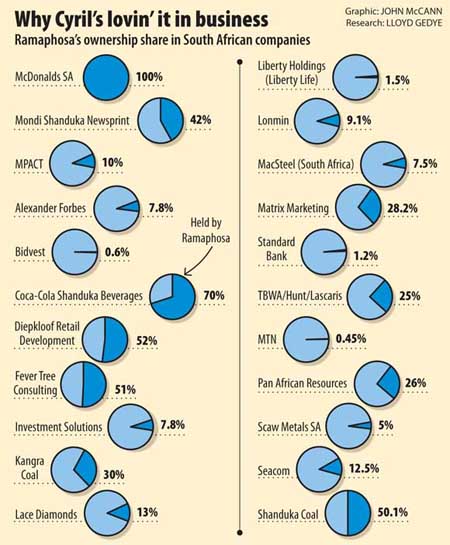

Graphic: John McCann

Comrades repeatedly recount anecdotes in Butler's biography about how Ramaphosa's biggest regret was that he had not been a miner so that he could have known their struggle more intimately and personally.

Ramaphosa is also quoted as saying, "The law is one of those professions that tend to promote bourgeois tendencies", which is in stark contrast to his recent calls for law and order.

Divergence

Ramaphosa's political career is so wrapped up in the NUM that when it was time to vote in the first South African democratic elections on April 27 1994, he did not vote in Soweto, his home ward, but at the first mine at which the NUM had organised, Kloof Gold in Westonaria, Gauteng.

In Butler's biography, Ramaphosa recalls the moment. "I was stopped by one old miner … who said: 'We are pleased you are here … I can now go and retire because what we fought for all these years, and what you also came and fought for, has now been attained and I can go and retire, and your coming here shows that you have come home – you belong to us miners.'"

But the question has to be asked: do the working class and the striking miners still feel the same about Ramaphosa in 2012? After all, this is the man who the Sunday Times Rich List named as the second-richest black South African businessperson, after Patrice Motsepe.

The divergence between the two Ramaphosas is distinct, which raises the questions: Who is the Ramaphosa of 2012 and what does he stand for?

The ANC Youth League, which is backing Motlanthe as president of the ANC, last week released a strongly worded statement vilifying Ramaphosa.

It said: "Comrade Cyril Ramaphosa has lost any credibility as a genuine leader of the people and a revolutionary committed to the cause of the working class."

Blood on his hands

The league said Ramaphosa had "delivered the more than 40 people to their death at Marikana" and accused him of having "blood on his hands".

The vitriol was intense, although the accusations are hardly based on fact. Since the youth league is not in the Zuma-Ramaphosa camp, is this genuine outrage or cheap politicking?

Ramaphosa's response was to state publicly that he would testify before the Farlam commission.

The fact that Ramaphosa finds himself in this position is bizarre; after all, this is the man who effectively built the NUM into the powerful machine it is today.

In 1982 Ramaphosa started a union for mine workers, which was commonly called the NUM. He was elected general secretary, a position he held for the next nine years, until he was elected secretary general of the ANC in June 1991. Under his leadership, the NUM grew from 6 000 in 1982 to 300 000 in 1992.

Ramaphosa was also influential in the setting up of Cosatu in 1985 – an effort through which his relationship with the ANC grew.

In 1994, when Ramaphosa lost out to Mbeki for the position of ANC deputy president, it signalled a massive change in his political future.

Obstacle

According to Butler's biography, Ramaphosa sulked and declined president Nelson Mandela's offer to be foreign minister. He also did not attend Mandela's inauguration on May 10 1994.

It is clear from Butler's book that Ramaphosa had aspirations to hold higher office. In fact, there are several quotes from comrades, colleagues, friends and former employers recalling the young Ramaphosa's ambition. These quotes generally follow the pattern of "When I am president …"

His defeat by the Mbeki camp had placed an obstacle in his way.

It was Dr Nthato Motlana, Mandela's old physician from Soweto, who approached the president, arguing that Ramaphosa's skills could be used in business, particularly by Nail, the empowerment company set up by Motlana, Dikgang Moseneke, Franklin Sonn, Paul Gama and Sam Motsuenyane.

"At the age of 43, Ramaphosa could afford to wait out a Mbeki presidency and return to fight again as a relatively young man," says Butler in his biography.

Eventually a meeting was held between Motlana, Mandela and Ramaphosa.

Long expressed

Ramaphosa was not initially convinced, but soon agreed to be deployed to the private sector.

According to Butler, Ramaphosa had "long expressed" an ambition to run a mining house.

"He felt confident that he had learned enough in his years at the NUM to run mines as profitably as – and he believed more humanely than – Anglo ever could," says Butler.

So, when Nail secured the empowerment deal for Johnnic and lost out on the deal for mining company JCI, Ramaphosa was bitterly disappointed.

But despite some early setbacks Ramaphosa became an empowerment icon, amassing vast amounts of capital from his years in business. Over the years he would secure interests in mining operations, including Lonmin.

Ramaphosa's political connections and success in concluding empowerment deals has naturally resulted in allegations that he is a black economic empowerment (BEE) fat cat.

Moeletsi Mbeki has described BEE as "buying" black members into the consumer "exploitative club" of established white South African business.

But many of Ramaphosa's comrades and colleagues point out that his first love was always politics.

Politically sensitive

Prominent businessperson and Ramaphosa's former sparring partner at Anglo, Michael Spicer, said: "Cyril's first love is politics … he is not really interested in business … for him, it's just a vehicle for the necessary accumulation of wealth."

So why is Ramaphosa's situation now so politically sensitive?

Ultimately, the deal struck between the ANC and white capital in South Africa in the late Eighties and early Nineties in which racial ownership was traded for liberal economic conditions is at the heart of the current ructions in the party. Ramaphosa, one of the most easily identifiable beneficiaries of this trade-off, is naturally at the forefront of the debate.

It is inevitable that the contrast between Ramaphosa's position in 1982 and that of 2012 will make some feel uncomfortable, particularly because the mining company of which he is an empowerment partner is accused of underpaying miners and making them work in harsh conditions.

Many read Ramaphosa's initial offer of a financial contribution to all families of the miners who died at Marikana as an admission of guilt.

Expectations

"At this moment, our main concern is for the families of all those who have been killed and wounded in these clashes," said the Shanduka Group.

"In the wake of this national tragedy, it is critical that all parties take meaningful steps to ensure that nothing of this nature ever happens again.

"For this reason, Shanduka Group supports a full and thorough investigation into the circumstances that gave rise to this incident."

Ramaphosa's insistence that he will testify before the commission should be applauded, but expectations of finding evidence of a smoking gun in his hand are far fetched.

His involvement in the Marikana massacre should prove to be tangential at best, a result of the ANC's decision to deploy their former prodigy to the private sector.

But what is more interesting is who exactly Ramaphosa is now, what does he have to offer the ANC and the country, and does he still have the stature among South Africa's working class that is imperative for any future leader of this country?