"The gentleman I'm touching right now," the hypnotist says as he places his hand on the shoulder of a chubby young man wearing a Springbok rugby shirt. "You are the minister of health, wellness and [pause for effect] hand-washing!" he booms from the stage.

"During interval, hover around the bathroom doors and check that each and every person has washed their hands," he instructs.

The owner of the voice is Andre the Hilarious Hypnotist performing at Montecasino in Johannesburg in March. "If you find any person who has not washed their hands, send them straight back in and do not let them out until they can prove otherwise," he says as riotous laughter erupts from the audience.

"When I snap my fingers, you are wide awake," he says to the man in the rugby shirt and the other people on stage with heads lolling on their shoulders, seemingly fast asleep. He snaps his fingers and they all immediately sit up – some with dazed and confused expressions on their faces.

"Have a lovely interval everybody!" Andre waves as he walks off the stage.

The word "hypnosis" conjures up images of people pretending to be washing machines, sprinklers, seagulls and any number of inanimate or bizarre things. One thinks of the master puppeteer on stage with the power to make one forget one's name or that the number four exists. I must add, it is undeniably funny to see a fully grown and educated adult deal with this situation: "One, two, three [confused expression] … five."

To satisfy my curiosity, I went to a private hypnotherapy session in Johannesburg. With eyes closed and hugging a large pillow, I spoke about my problems prompted by questions from a very pleasant hypnosis practitioner. While talking, I waited for the moment when everything would go dark and I would wake up suddenly to the sound of clicking fingers – minus an hour of my memory. That moment never came. I remember it simply as a very relaxed and introspective conversation – like a more tranquil version of a routine visit to a therapist, with the added scent of lemon-grass incense and the soft sound of wind instruments.

In my search to find the answer to what hypnosis is, how it works and whether it's even real, I found the truth to be quite an anticlimax. It's a simple and straightforward phenomenon backed by logic – not the mystical and powerfully magical art I assumed it to be.

How it works

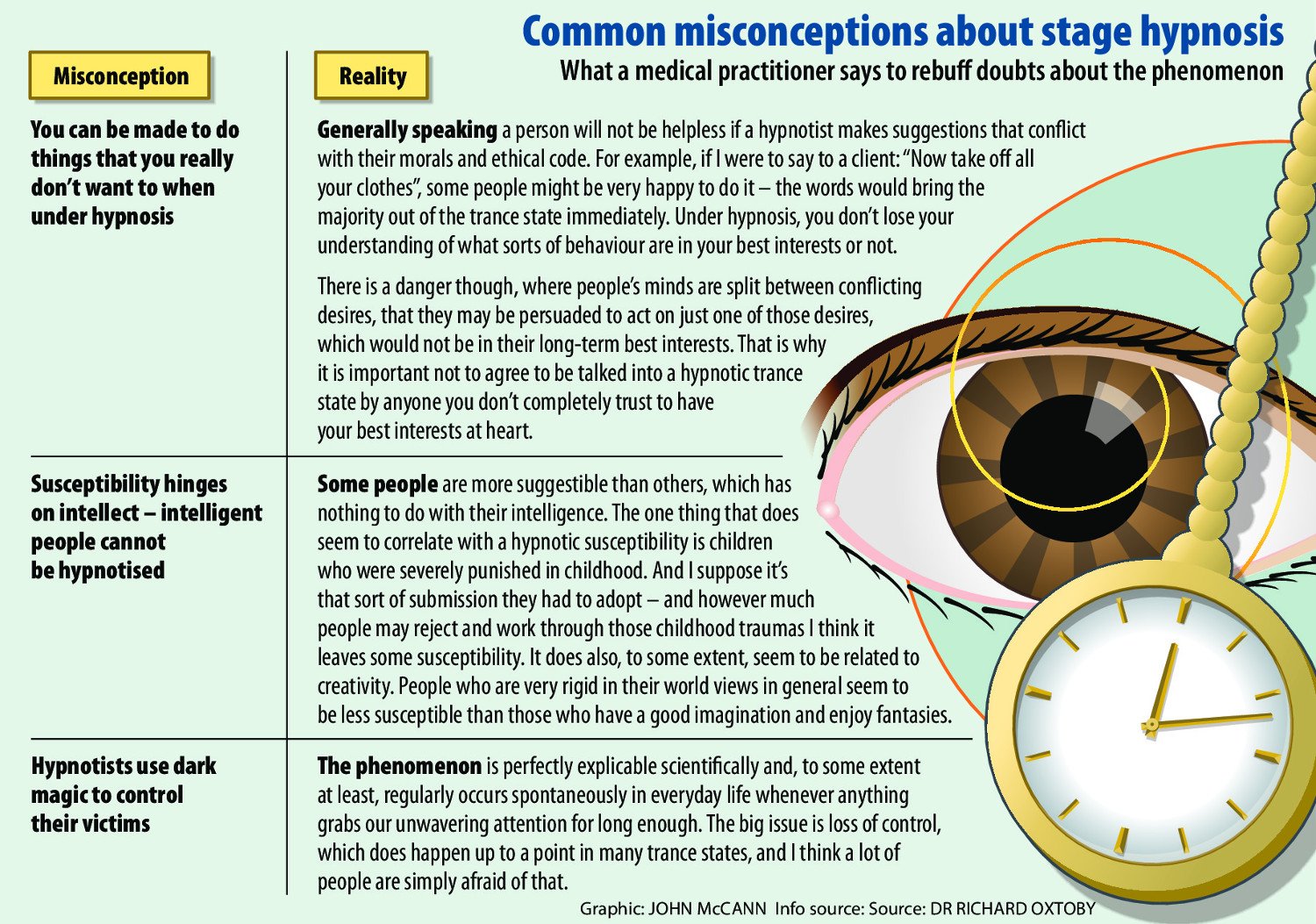

"Hypnosis is all about the direction of attention," explains Dr Richard Oxtoby, a psychologist and retired lecturer at the University of Cape Town's psychology department.

Unlike most of his peers, Oxtoby devoted some of his time in academia to exploring hypnosis. He also uses hypnotherapy in his private practice.

"Our normal waking state is one of constantly fluctuating attention – something may grab your interest and, for a time, you focus on it. But before too long you hear a sound and your attention shifts," he says. "Under hypnosis one's attention, instead of naturally wandering, is focused in a very narrow band."

Hypnosis as a therepeutic tool

Oxtoby uses the therapeutic benefits of hypnosis in a technique he terms the "rewriting of personal history". He says past traumas can have a particularly debilitating effect on a person's life.

"People take away from traumas a belief about themselves, especially if they were very young. A belief that they're bad, that they brought this upon themselves in some way. And it's those attitudes of self-blame and lack of self-worth which can be very successfully altered under hypnosis," he says.

Under hypnosis, Oxtoby takes his patients back to traumatic periods in their lives by using their imagination. "I get them to identify that feeling then to ask them to imagine they are now this little boy or little girl – and then imagine that their adult self comes up to this child, sees them and comforts them."

The trauma is relived and reimagined in the mind of the patient. Oxtoby says the adult self is able to explain to the traumatised child that "whatever they might've done and shouldn't have done – it was a totally inappropriate and cruel response on the part of whoever punished them in that way".

Johannesburg-based hypnosis practitioner Yvonne Munshi uses the same technique to help her clients: "I think what we all want more than anything else in the world – whether we're six months old or 70 years old – is to feel good about ourselves. Using hypnosis, we can change the feelings we have about ourselves. We can create new memories and feelings of kindness and understanding instead of only remembering punishment."

Oxtoby says another important clinical benefit of hypnosis is stress reduction: "Most relaxation techniques [like yoga for example] have a hypnotic component to them. The benefits of relaxation and the release of stress can be enhanced by the appropriate use of hypnosis – it's a largely untapped resource."

Oxtoby believes that "more people, especially in the health professions, could be inspired to explore this powerful technique". He says the principles of hypnosis can be used by any healthcare professional to relax patients, potentially making treatment easier and more pleasant for both patients and doctors.

Changing notions of hypnosis

Unknown to most, according to Oxtoby, hypnosis is a part of our everyday lives. "One can enter that hypnotic trance state just by being captivated by a beautiful sunset or a magnificent work of art."

This is very different from conventional notions of hypnosis. "There are two very different approaches to hypnosis," explains Oxtoby. "The one is the traditional approach, a very authoritarian one, which one sees with stage hypnotists: ‘I'm going to put you in a trance and make you do whatever I want to make you do'."

He says that was the understanding of hypnosis until the middle of the previous century, when American psychiatrist Milton Erickson developed a completely different approach – what he called "a permissive approach".

"So instead of exploiting a power relation with the client, he would more or less seduce the client. More like: ‘If you would like to, you would probably find you're experiencing so and so,'" Oxtoby says.

"I think professional people with very few exceptions use the permissive approach."

Professor Mark Solms, head of the University of Cape Town's psychology department, agrees with Oxtoby about the misconceptions created by stage hypnotists.

"Doubts about hypnosis and its scientific credibility arise mainly from wild claims made about its mechanism at the turn of the last century, and unprofessional and theatrical applications of the speciality," says Solms.

Although hypnosis doesn't really feature in university curricula in South Africa, Solms says it is a very real phenomenon.

"Understanding the mechanisms of hypnosis reveals important facts about attention, self-awareness, volition and free will," he explains. "Furthermore, the brain images of people in hypnotic states demonstrate unequivocally that the brain is in an altered state under hypnosis."

Stage hypnotist Andre Grove (Andre the Hilarious Hypnotist), says: "In my shows it's not hypnosis that plays the overwhelming role."

He says that the far more specialised and demanding part of his shows is the performance side.

"I can teach you how to do hypnosis in an hour, but you can't be taught how to be a performer," he says. "It took me a lifetime to become the overnight success I am now."

Selection process

But that doesn't explain how he makes people do such outlandish things on stage.

"There's a selection process," explains Oxtoby. "Actually the secret of the hypnotist's power doesn't lie so much in what he does with the subjects who are up there on the stage, but more in how he selects from the whole group who are present."

Andre's selection process began with calling anyone who wanted to volunteer on to the stage. I threw caution to the wind and volunteered myself. Among other things, he asked us in a low, steady voice to close our eyes, breathe deeply, relax and interlock our hands.

"You will now try to pull your hands apart," he continues in a soft monotone, "and you will find you can't – they are stuck together."

I tried to pull my hands apart. And I did.

The less suggestible people, including myself, leave the stage as Andre skilfully selects volunteers.

I walked back to my seat still asking what hypnosis was really about. During interval, I went to the toilet. As soon as I walked out, I remembered that the new "health minister" would be hanging around.

The "minister" holds up his hands and, with a stern look on his face, says: "Stop. I'm inspecting hands. It's a new government regulation. What's this black stuff?" he raises his voice and looks accusingly at me.

Unfortunately, I didn't thoroughly wash off all the ink residue left from my note-taking during the show.

He points to the bathroom and shifts his posture to make sure I know I will not get past him without a fight.

My face reddens as I turn around and walk straight back into the bathroom. I feel like a naughty child. After scrubbing for a good few minutes I cautiously walk out again.

He grabs my hands and pulls them to his face again. Almost begrudgingly, he says: "OK, you can pass."

Unclear law leaves practitioners inthe dark

"Since 1997, every few months some panic surfaces in the hypnosis community regarding the law," says Leo Gopal, a research psychologist and founder of the South African Hypnosis Network – a nonprofit network for all hypnotists in the country.

Gopal is referring to the Health Professions Act, which, in 1997, was amended to include "hypnosis and hypnotherapy" as actions to be solely performed by a licensed psychologist or mental health practitioner – making the practice illegal without this professional status.

There are countless "hypnotherapists" practising in South Africa, and many schools that train them, but who are not trained and registered psychologists. The Act also made stage hypnotism an illegal practice, but was amended in 2007 to allow them to continue performing.

"This amendment allowed us to breathe a sigh of relief," says Gopal, "It allowed some leeway in our profession."

The act of hypnosis was no longer illegal for hypnosis practitioners but they were not allowed to describe themselves as hypnotherapists.

"It's a grey area under much debate," says Gopal.

Hypnosis practitioner Yvonne Munshi, says the wording of the Act is a problem of semantics. She is redesigning her website to replace the word "hypnotherapist" with "hypnosis practitioner".

"But people don't know this. They look for hypnotherapists and not hypnotists. If people ask me if I'm a psychologist, of course I say no, but not being able to use the word therapist negatively impacts on my business. It's a catch-22 situation."

Gertie Pretorius, vice-chairperson for the professional board of psychology of the Health Professions Council of South Africa, says the council is "concerned" about the number of unregistered and unqualified people practicing hypnotherapy.

"There are huge risks involved because only a registered psychologist would be able to recognise the worrying signs [exhibited by a distressed patient in therapy]," she says.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Exploding 'supernova' captured in my fist

"Very often people come in here and they think I'm going to whack them over the head with a rolling pin and they're going to walk out of here a nonsmoker and not remember anything that's happened," says hypnosis practitioner Yvonne Munshi as she prepares me for a hypnotherapy session at her Bryanston office.

"Hypnosis is a state of altered awareness," she says. "It is not sleep, not unconsciousness. It is, in fact, a state of heightened awareness during which the logical mind is bypassed and dialogue is held with the subconscious mind."

Munshi sits opposite me and places a large pillow on my lap. "Lean back and relax," she says.

She stares at the forms she has filled in with my answers to some basic questions: "How old are you? What is your relationship with your family like Any history of depression, drug or alcohol abuse, and phobias or general problems?"

She looks up again and smiles reassuringly at me. "Let's put some music on."

I concentrate to hear the almost inaudible sound of flutes over the rumble of Johannesburg traffic outside the window.

"Since you are generally quite stressed and you put a lot of pressure on yourself, how about the first thing we do is give you a little tool so you can experience a bit of what a trance is like."

I nod.

"This is your stress ladder," she says while sketching a ladder on a piece of paper. "With deadlines and stress and constant demands on us, we tend to go up that ladder. To bring ourselves down we can use our imagination because it is an incredibly powerful tool."

She asks me to imagine three images: a "happy heart", a "peaceful mind" and "playfulness of spirit".

"For example, my peaceful mind image is of Knysna at midnight beside the lagoon," Munshi says in a hushed voice. "The moon is shining on the water – it's just beautiful."

She gently directs my hands to lie flat on top of the pillow on my lap. Following her instructions, I take a deep breath, close my eyes and lay my head back on the couch. "There you go. Much better," she says soothingly.

After I pick each image, she asks me to "sink into the feeling" – to think about it alone and to let it overwhelm me. "Take a deep breath and sink more into the feeling," she commands softly.

"What symbol can you give these three images?" she asks.

In the moment, all I can imagine is a supernova exploding in a sea of light.

"Wonderful! Now make a fist with your right hand and hold on to that star. Imagine you can hold on to the feeling of that exploding star.

"Every time you want to be in this place – how you are feeling now; happy, peaceful, playful, excited, free – all you need to do is take a deep breath and make a fist with your right hand because it is anchored here," she says, touching my clenched fist.

She counts from five to one and asks me to open my eyes. I feel good, like a warm wave has washed over me.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Hypnosis can help in a range of treatments

Dementia

A 2008 study by the University of Liverpool showed that hypnosis can help patients suffering from dementia. Hypnosis was compared with a number of other treatments, including group therapy over a period of nine months.

Patients receiving hypnosis treatment showed improvements in memory, concentration and socialisation, but the patients in group therapy showed little to no improvement.

The author of the study, forensic psychiatrist Dr Simon Duff, said: "Participants who are aware of the onset of dementia may become depressed and anxious at their gradual loss of cognitive ability and so hypnosis can really help the mind concentrate on positive activity like socialisation."

Breast Cancer

Using hypnosis before breast cancer surgery can reduce post-operative pain, nausea and lower treatment costs, according to a study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2007.

Half of the sample of 200 women received a 15-minute session of hypnosis from a psychologist before surgery, and the other half spent the same time talking to the therapist. Patients in the hypnosis group required less anaesthetic and spent an average of 11 minutes less in theatre, resulting in cost savings of $773 a patient.

Hot flushes – menopause

Hot flushes caused by menopause were reduced by up to 80% by weekly sessions of hypnosis conducted by clinically trained therapists, according to a study undertaken last year by Baylor University's Mind-Body Medicine Research Laboratory.

Over five weeks, 187 women participated in "hypnotic relaxation therapy" and, on average, flushes reduced in frequency as well as intensity. The authors of the study said this intervention may appeal to women because of the low cost compared with medication.

Source: Professor Mark Solms, psychology department, University of Cape Town