On track:Despite losing everything in his bookshop in Kibera

Khaleb Omondi stood looking at the empty plot in front of him. He gaped at the space where his bookstore once stood, on the northern side of the train tracks in Laini Saba, one of Kibera’s 12 villages. The only thing the looters did not take –could not take–was the ground that had held up the mabati (corrugated iron) structure. It had taken 12 years to become the largest bookseller in Kibera, and in 12 hours it was all gone.

"Twelve hours," he told me. "That was how long it took for them to carry the stock that I had in my shop." He shook his head and smiled wryly, the sinister symmetry not lost on him. "That was how short it took to destroy my life."

Omondi is not sure how long he stood in front of the empty plot. But he eventually left and walked in a daze through one of the world’s most notorious slums, his home for 12 years. So many questions ran through his mind–where would he find money to rebuild? What about his children’s education? He had just married a second wife. How would he meet his obligations to his growing family?

He left the slum behind him in a stupor and did not see the car coming. All he remembers is waking up in Kenyatta National Hospital a few days later.

"It was a very hard time for our family," his first wife and business partner, Tabitha Sungu, recalled five years later. "Everything, everything we had built was gone, and now Baba Pius was in hospital."

In Kibera, Baba Pius, as Omondi is known, is held up as something of an icon by survivors of the 2007 post-election violence. For many–Luo, Luhya, Kamba, Kikuyu–he symbolises the devastating impact that the violence had on good, hard-working families in the slum. He also mirrors what many identify as their story, the sheer strength of the human spirit to survive against all odds. The spirit of Kibera.

When I first met Baba Pius, he was standing behind a glass cabinet at Kinda bookshop’s second branch, Jo Kinda, where the latest textbooks catch the eye of passers-by. Jo Kinda is just outside Kibera in the nearby middle-class Magiwa estate, a 20-minute walk from Omondi’s first store. "I opened this bookshop in 2008, after I came out of hospital," he told me. "I had to find a way to continue supporting my family. I decided to rent this store while waiting for things to cool down in Kibera and give me time to find money to rebuild."

Jo Kinda juts out of the back yard of a two-storey house and faces the main thoroughfare into and out of Kibera’s Laini Saba entrance. By ordinary standards, Jo Kinda’s location is a great catchment area for customers. Every few minutes, matatus (minibus taxis) drop off or pick up passengers going into or out of the city. It is a busy street.

Yet despite its prime location, it is the Kibera store, Kinda, that makes the profits needed to send Omondi’s children to school, pay for clothes and finance family emergencies.

Omondi is soft-spoken and unpretentious. His mild countenance and soft brown eyes give a hint of sadness, but none of the bitterness that hardened scars betray. Kinda, (pronounced "keenda"), the name of Omondi’s first bookshop, "is a Jaluo word for endeavour," he said, as he sold past exam papers to a young man. "Jo Kinda, the name of my second bookshop, means people who endeavour to succeed."

Omondi was 19 when he moved to the slum from his ancestral home, Bondo, in Nyanza province, western Kenya–about 320km from Nairobi. His father was a carpenter and his mother sold vegetables at the town market, which she grew on their smallholding.

When his father died in 1992, the family lost its primary breadwinner. "I had to drop out of school to take care of my younger brothers and sisters." With his father’s responsibilities on his shoulders, Omondi moved to Kibera in 1994, and shared a 3m2 room with his uncle. He found work cleaning offices in Nairobi’s city centre. His shift ended early and, at three in the afternoon, he would set up a makeshift rack by Kibera’s rail tracks and sell malimali (knick-knacks)–cigarettes, matches, sweets–to supplement the 1?375 Kenyan shillings (about R170) wage he earned each month. It gave him a little extra income, but not enough to leave his cleaning job. After a short trip home for Christmas, at the end of his first year in the big city, he brought back his old school books, hoping he could sell them.

"It started as a joke," said his first wife, Tabitha, when I first visited Kinda in Kibera. I could barely make out Tabitha’s handsome face in the dark store. She was standing behind a wire barrier that blocked entry into the shop.

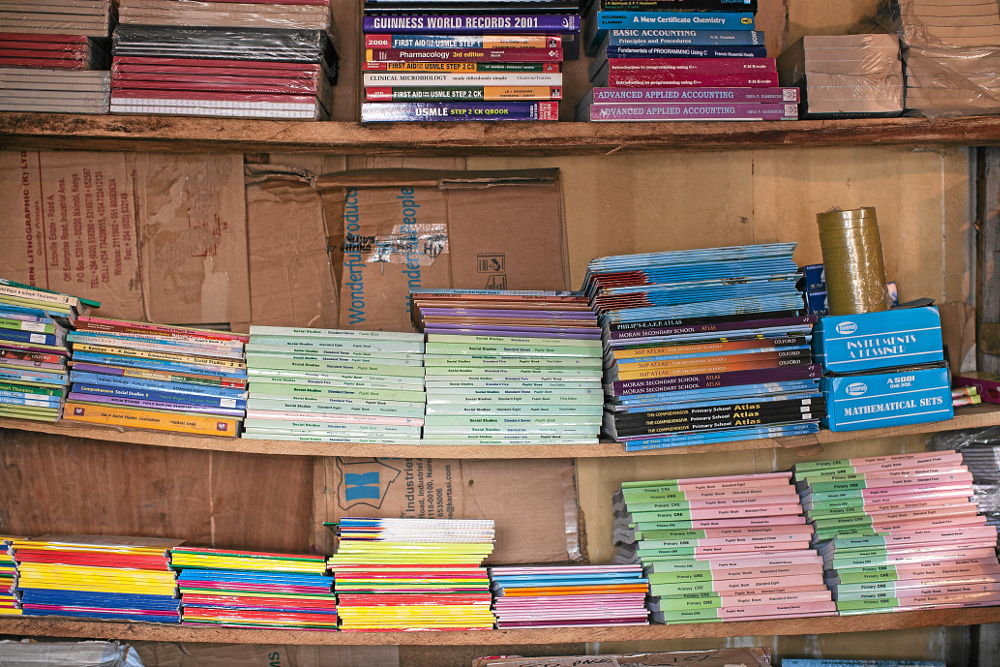

Like her husband, she is soft-spoken and reserved. At 1.67m, the books packed from floor to ceiling imposed on her like a monument. I stood mesmerised for a few seconds as I took it all in. Every inch was filled with books. Chemistry books, physics books, mathematics books, geography, civics, literature. There were Swahili and English language books for all grades. Whether one had just started school or was attending university, there were books covering a whole range of different subjects.

Each section is colour coded. I remarked on how neat the bookshop was. "Baba Pius is the one who organises it," his wife said.

"No one had any use for the books back home, and it seemed a waste for them to sit there gathering dust. I had at least 50 textbooks," Omondi said as he explained how he started Kinda bookshop.

Much to his surprise, the old school textbooks sold quickly. "People would come past my rack and ask me: ‘Do you have this book’ I got so many requests that I decided to focus my efforts on selling books." Emboldened by the demand, Omondi borrowed the equivalent of R1000 from friends and relatives to start a second-hand bookstore.

By the time Omondi moved to Kibera in 1994, it was home to at least 700 000 people–at least those were the figures that urban planners, historians and United Nations agencies quoted. When the country’s 2009 census counted 170070 Kiberans, the slum–and nation–were plunged into an identity crisis. "Myth shattered: Kibera numbers fail to add up," screamed a Daily Nation headline. Having lost its nefarious yet prideful place as Africa’s largest slum, what was Kibera other than just another ordinary place?

The controversy over numbers continues. Some argue that the government census was an undercount, others blame international organisations and nongovernmental organisations for inflating population figures in order to get funding. Whatever its numbers, Kibera’s location close to the central business district, the industrial area and employment opportunities in neighbouring housing estates has attracted people from all over the country over the course of its history.

But the second-hand book market was good business for Omondi. On average, he made the equivalent of between R10 and R15 a book.

"The demand was always there," he said.

In 1996, Omondi married Tabitha. But second-hand bookselling had its limits. "When I was selling second- hand books it was difficult to find books people wanted, and to find sellers with those specific books. In 1997, I made the decision to sell new books."

Using the capital he had accumulated from his malimali sales, he built Kinda and stocked it with school textbooks.

Omondi is stately and reserved, but get him talking about books, and he becomes easygoing and animated. "A good business," he said, "depends on stock. All the money I make I put into my stock so that when people ask for a book from my shop they never miss it."

Omondi has found a niche market in the sale of educational books. "For college books, you have to stock the latest edition. Nobody in Kibera will buy an old edition. If it is school textbooks, you need to know which are the set books for the coming year. You are constantly updating your stock," Omondi said.

For the most part, his flair for the book business has served him well. In 2002, he had made enough to buy land for his store in Laini Saba. This was no mean feat. Before the 2007 post-election violence, Laini Saba was to Kibera what Sandton is to Johannesburg–the slum’s most valuable real estate.

The shop owners here are referred to as watajiri wa Dubai (Dubai’s wealthy class). Indeed, Laini Saba is Kibera’s Dubai, where knock-off designer clothes, construction materials, black market DVDs, electronics and every imaginable item is for sale. When the government offered free books in schools in early 2000 his business slowed down, but he still made an income that allowed him to support his family.

"A good parent will buy a book for their child," Omondi said, explaining how his business continues to survive. "So if you don’t want your child to share, that is when we make business."

In an area where almost 50% of the population live below the poverty line, few think of Kibera as a place where people have an interest in books or education. But there is a reverence for education in the slum that is sacred. Here, parents will sacrifice almost anything, even a life in a middle-class home with space, piped water and flush toilets, to send their children to good private schools, pay for extra tuition and buy books.

Omondi is a meticulous businessman, but it also helps that he is a lover of books. "This is not just about business for me," the 39-year-old said. "Books make me happy. Since I was a boy, I have loved books. I didn’t complete my schooling but I read. I have a lot of time sitting in my shop waiting for customers. So I sit and read. I like Danielle Steel, Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Ngugi wa Thiongo’s The River Between.

"I am drawn to reading," he said, "because of the lessons contained in books. Every book has a lesson I can use in my own life. It is books that have helped me heal and forget what happened to me in the violence of 2007 and give me strength to move on."

Photography by Nick Kozak

Photography by Nick Kozak

In December 2007, Omondi’s life went up in flames. The store he had built was destroyed in politically motivated violence. The riots began on December 30 2007 after Mwai Kibaki was sworn in as president. Some of Kibera’s residents believed that Kibaki, a Kikuyu, "stole" the elections from his rival Raila Odinga, a Luo. There was looting and burning of shops in the slum as militia groups formed in support of the two presidential candidates. Luos in Laini Saba, a Kikuyu stronghold, were targeted by Kikuyu militia, the Mungiiki. In this mayhem, Baba Pius lost everything he had worked for.

According to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, about 1?200 Kenyans were killed, 300?000 were displaced and millions of Kenyan shillings worth of property and goods destroyed during the post-election violence. Kibera was one of the most affected areas in the country.

When I conveyed these facts to Omondi, his face went blank. Official numbers and reports have a way of removing the emotional sting of traumatic events in ways that alienate personal experience.

Omondi responded to my figures. "In all the years I have lived in Kibera, I have never experienced or seen such violence. No, that is not true. In all the years I have lived, I have never experienced such violence."

"I don’t ever want to go back to those days again," Omondi said, shaking his head. He estimates he lost at least R375?000 in the violence. "These were people who are known by the community. We see them passing here every day," said a businesswoman whose store is not far from Kinda bookshop.

This is perhaps one of the most difficult things to come to terms with. How people who have shared a meal, taken care of each other’s children and contributed to the burial of a neighbour can turn on each other.

Omondi broke one of his legs in the car accident and it was in a cast for nine months. For a year after the violence, he could not afford to send his children to school. He rented a stall in Magiwa, with money borrowed from his family, where he established Jo Kinda while he rebuilt Kinda in Kibera.

He had no money to buy books for cash. "But I was lucky because I had a relationship with my suppliers, so I was able to get a few books on credit." He has rebuilt his Kibera store, but it does not compare in size and stock with the old bookstore. "The original Kinda," his wife told me, "was bigger than it is today. It will take time to get back to where we were."

Kibera has a magnetism that both attracts and repels. It is these characteristics that make it as alluring as it is terrifying. "I will never leave Kibera," Omondi said adamantly. "If I leave Kibera it will be to go back to home square." "Home square" is the local euphemism for ancestral home.

The last time I saw Omondi, a month after Kenya’s March 2013 elections, he was carrying a carton of books back to his Kinda shop. He and his wife had emptied Kinda’s stock before the elections, to minimise the loss from possible violence and looting. A month after the elections, Omondi was restocking his store, now hopeful that all was safe.

The community may have dodged violence in the 2013 elections, but it has by no means healed from the wounds of the past. Omondi now spends most of his time in Jo Kinda while his wife takes charge of the Kibera store. I wondered whether the trauma of facing people who may have been complicit in stealing everything he had is too painful.

When I asked him how he felt about what happened, he responded realistically: "Ni watu tu [they are just people]. I am a businessman, and they are also my customers." Whether it is the practicalities of having to live together, their dependency on each other, or even an acknowledgement that fate has brought them together, it is perhaps stories like Omondi’s, the keeper of books, the community’s hope for future generations, the triumph of the human spirit, that gives Kiberans a chance at a better life.

This is an edited extract from "The Bookseller of Kibera", part of a collection of stories in Writing Invisibility: Conversations on the Inner City, an e-book published by the Mail & Guardian in association with the African Centre for Migration and Society, and supported by the Max Planck Institute. Go to mg.co.za/acms to download a free copy of the book.