Although property, jewellery and cars represent obvious signs of wealth, there is another, less apparent indicator of the country’s growing affluence: the food South Africans are putting on their plates.

Although property, jewellery and cars represent obvious signs of wealth, there is another, less apparent indicator of the country’s growing affluence: the food South Africans are putting on their plates.

Over the past two decades, as the average income in the country has risen, meat consumption levels have skyrocketed.

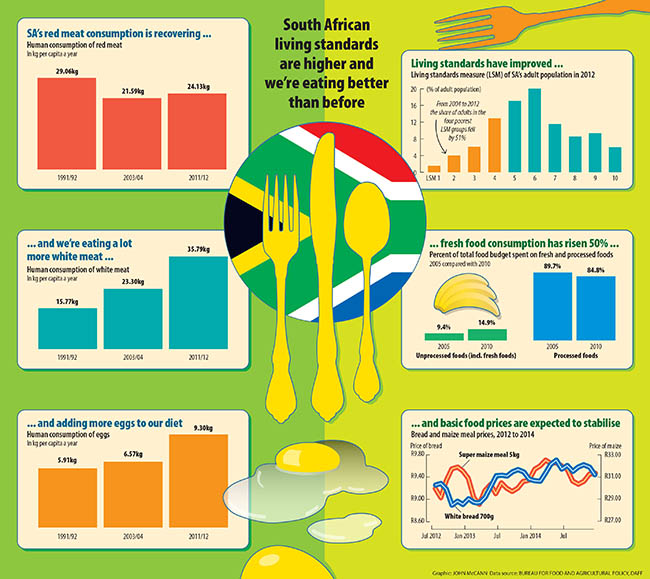

In 1992, the average person ate a total of 15.8kg of white meat a year, according to the department of agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

The nominal gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was $3.39 at the time.

Twelve years later, the average South African ate 23.3kg of white meat a year — an increase of 48%. According to the International Monetary Fund, the GDP per capita in that year had risen to $4.47.

By 2012, the consumption of white meat had increased by another 54% to 35.8kg a person a year. In the same year, the nominal GDP per capita had risen to $7.51.

Egg consumption

Egg consumption followed a similar pattern. In 1992, the average South African ate 5.9kg of eggs in a year.

Fourteen years later, that had increased to 6.6kg. Last year, it had surged to 9.3kg, meaning that, during the past 20 years, egg consumption here has more than doubled.

According to Hettie Schonfeldt, a professor at the University of Pretoria and an associate at the Institute of Food, Nutrition and Wellbeing, the numbers show that, as disposable income increases, the nation’s fondness for meat is being reflected by its buying behaviour.

Global trends show that shoppers in other emerging economies also head for the meat aisles when given the chance.

Brazil ate 43% more meat in 2009 than in 1999 on the back of growing prosperity and China’s meat consumption increased by 58% over the same period, according to Researchscape.

“In marketing terms, the demand for meat is latent, meaning that people do not need to be encouraged to eat more meat, only that they need to be able to afford to do so,” said Kevin Lovell, chief executive of industry body SA Poultry. “People like the taste and texture of meat and it is socially aspirational.”

Shifting consumer base

The Bureau for Food and Agriculture said a shifting consumer base has allowed for the increased trade volumes.

“Rising incomes is a key factor underlying changing consumer trends,” it said in its baseline 2013 report.

“In the South African consumer market, consumers have moved towards higher LSM [Living Standards Measures] groups driven by economic growth as well as socio-economic empowerment.”

Between 2004 and 2012, the number of South African adults in LSM segments one to four (the poorest segments of the market) “declined dramatically by about 51%”, the report states.

At the same time, LSM seven (with an average monthly income of R10 000) saw an 86% growth and LSM eight (an average income of R15 000) increased by 78%.

“The significant shift in the consumer market to higher LSM groupings provides reason to suggest that dietary habits would also have significantly changed,” Schonfeldt told the Mail & Guardian.

However, there is a significant lack of recent studies on actual food consumption in South Africa. This means that current information represents macro trends and figures, and does not indicate meat consumption per geographical location.

Meat consumption

And it is obvious that meat consumption levels will not keep climbing hand in hand with wealth indefinitely. Eventually, “it does reach a plateau”, said Schonfeldt.

Although South Africans are considered to be avid meat eaters, most are still eating less than the 80g to 90g of lean cooked meat a day recommended by the South African food-based dietary guidelines, said Schonfeldt.

A study by the British Nutrition Foundation showed that meat consumption in the United Kingdom continued to rise over the past decade, despite there being a high level of food security and wealth.

In 2009, adult men in the UK ate 217g of meat a day, almost three times the recommended average for South Africa, and adult women ate 161g.

South Africa could be decades away from reaching these levels.

“In South African terms we feel that volumes could easily be increased by 50% if disposable incomes allowed it,” said Lovell.

Red meat vs white meat

Although red meat consumption has also increased, it has seen more moderate growth than that of white meat. In 2002, South Africans were eating 19.6kg a person of red meat a year. Ten years later, this amount had increased to 24kg, which, although higher, was still 25% lower than it was in the early 1980s.

“Price is the probably the main factor limiting consumption growth of red meat. This is hard to change as red meat animal types need more feed to produce food in the sense of protein,” said Lovell.

“Chicken does so well because it is inexpensive and ubiquitous. In Africa, chicken is king and likely to remain so.”

The trend is not only easier on the pocket, it is good news for health as well, with excessive red meat consumption being linked to several cardiovascular diseases.

And South African consumers have shown another healthy tendency: they are buying more fresh produce.

Between 2005 and 2010, the percentage of the South African food budget that was spent on unprocessed food (fresh fruit and vegetables) increased from 9.4% to 15%.

At the same time, “level one” processed foods such as wheat flour and maize meal decreased from 39% of the budget to 31.5%. Levels two and three processed foods, such as spaghetti and pre-packed TV dinners, however, increased.

So in some ways, it’s a mixed bag: while more affluent consumers are using their extra cash to buy fruit and veggies, they are also consuming more sodium-heavy food packed with preservatives. The change reflects an effort for consumers to match their eating habits with their routines, said Schonfeldt.

“People are constantly seeking solutions to fit in with the changing fast pace of their lifestyles,” she said.