New Nigerian photographer Lakin Ogunbanwo follows in the footsteps of the renowned studio photographers who captured Africa's popular culture as the winds of independence swept across the continent.

Ogunbanwo's work comes decades after Malian youth visited Malick Sidibé's studio, intent on being photographed by the famed portraitist. Likewise, and prior to that, Sidibe's countryman Seydou Keïta photographed fashionable Malians as they posed before his textured backdrops.

Chatting over Skype, Ogunbanwo views the images in his latest exhibition as a continuation of this photographic tradition. His body of work "is an extension of West African portraiture", he points out matter-of-factly. "I am Nigerian, and Nigeria is in West Africa, and these images were all shot in a studio."

But he recognises that his work takes the genre off its traditional course and into a space that he has defined for it.

This type of appropriation of a photographic style is not entirely new to sub-Saharan African photographers, whose studio shoots have left an indelible legacy on the art world.

Like Keïta and Sidibé, Oumar Ly of Senegal and Ghana's James Barnor adopted the studio photography practised from the mid-19th century by European ethnographers. But they updated it and put their own stamp on it.

These photographers of the 1950s and 1960s took the method of "documenting" Africans that European photographers practised in the colonies and made it their own.

How it all began

Born in Lagos in 1987, a year after Nigeria was rocked by a military coup, one of many, Ogunbanwo's love for photography grew as political turmoil engulfed his country. His love was unshakable, he tells me. He practised his art while studying law in Nigeria and the United Kingdom and, when the West African country's political climate eventually stabilised and Ogunbanwo returned to Lagos, he embraced photography completely.

Ogunbanwo's love of portraiture could as well have been described by Sidibé, who said in an interview in 2008: "You don't choose [photography]. You are called."

When the call came, Ogunbanwo enrolled at Paris's Spéos school of photography, where he fine-tuned his skills.

"Paris made me more fearless," Ogunbanwo says. In contrast to his early days as an untrained photographer in Lagos, in Paris "everything became more serious, more professional".

Upon his return to Nigeria in 2011, Ogunbanwo set up a small studio and, with a penchant for photography and "beautiful things", began snapping away at his subjects.

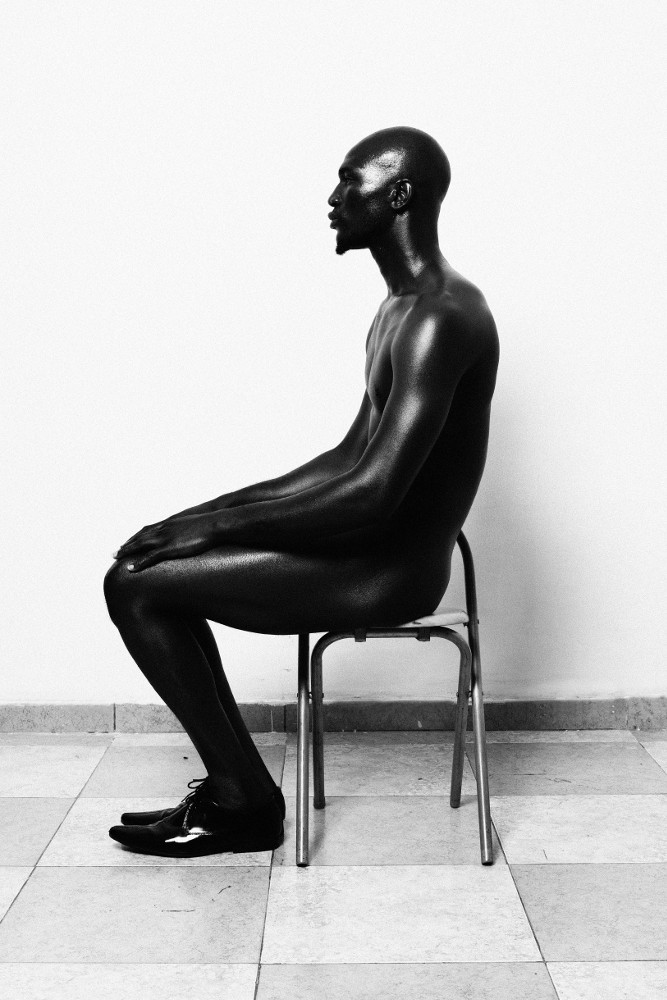

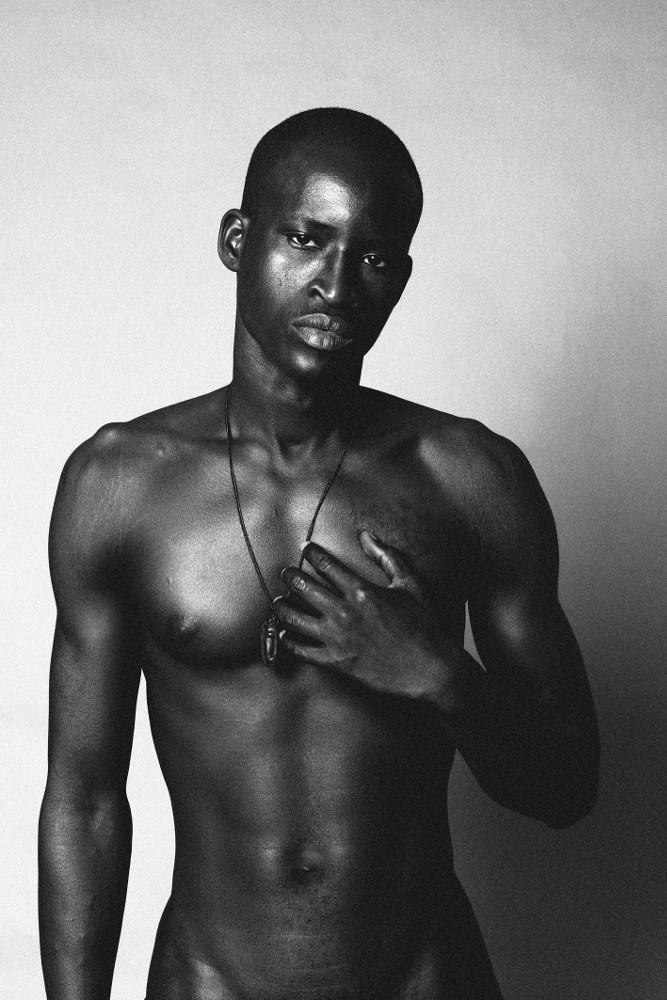

He shot tall, brown, sculpted bodies, models or "regular people, like myself". His palette was black and white, or a two-colour affair. Some subjects he captured naked, some fully clothed and others in only a pair of shoes or covered in flour.

"Lakin Ogunbanwo has emerged from the burgeoning advertising and fashion industries of the region, fusing a pop aesthetic with classic studio performance into a disturbing visual image-making vocabulary," curator and gallerist Roelof Petrus van Wyk says of the photographer's work. Ogunbanwo's exhibition is due to open at Gavin Rooke and Van Wyk's Johannesburg gallery next week.

Referring to himself as a "fashion and portrait photographer", Ogunbanwo unpacks his aesthetic: glossy and highly stylised images, "which, among other things, are about fashion and the mood".

Studios provide a controlled environment

In his photographs, Ogunbanwo's subjects seem to haunt the frame. Here are perfect specimens, apparently vacant enough to embody and carry Ogunbanwo's powerful vision, similar to how expressionless models in the fashion industry are used to carry designs down a runway.

But the people in his photographs are a far cry from those in the works of his predecessors Sidibé, Keïta, Ly and Barnor. Those subjects visited photographic studios to document their existence for their families, for posterity. Their faces, postures, clothing and props expressed vivid emotion as their countries made the transition into independence.

"In my country, the portrait incarnates photographic tradition," Sidibé told Le Monde's Michele Guerrin in 2003. "It also documents our history and people through faces, hairstyles, clothes … Clients want their faces and possessions to be seen."

Besides growing the tradition of African portrait photography, Ogunbanwo says one of the reasons for shooting in the studio is simply the creative control it offers.

"As opposed to photojournalism, documentary or reportage photography, shooting fashion and art in studio means that you – the photographer – are in control of everything in the frame," he asserts, adding, "I'm a bit of a control freak in that way."

Lakin Ogunbanwo's work from 'Portaits'. (Supplied)

An African capturing Africans

This meticulousness is not unheard of among studio photographers. Speaking to the Guardian newspaper in 2010, Sidibé said that in order to be a good photographer, one should have "a talent to observe, and know what you want. You have to choose the shapes and movements that please you, that look beautiful."

Ogunbanwo, meanwhile, says that the isolated subjects in his photographs reflect his own personality. He is "a solitary figure, so this work represents who I am. As I tell people: ‘I'm a loner, until I'm not [alone]'."

The many lonesome figures, presented against bare backgrounds, seem like denizens of a land far away from Lagos, notorious for its overcrowding. Despite being one of Africa's most fashion-forward cities, it's hard to avoid reports of state corruption, ethnic tension and unemployment – something not unfamiliar to other African metropolises.

Ogunbanwo reflects on the representation of Africa in the media, and on what is expected from photographers who capture Africans in Africa: poverty, hunger and general disaster.

"As photographers, we all have different stories to tell, and these stories will [be] reflected in the photographs," says Ogunbanwo, who was recently listed by CNN as one of Africa's most exciting new photographers.

"Lagos is incredibly busy and always bustling. However, there are parts of the city that are calm and serene," he says, adding that it is this quietness that influences his work.

Ogunbanwo touches on how the African marketplace has become a common theme for art and fashion photographs in Western media, and how there is a certain pressure to produce work depicting this.

But as his art pushes the boundaries of traditional studio photography, Ogunbanwo doesn't feel compelled to shoot Africans in a stereotypical manner: "As long as I'm the one holding the paintbrush or camera and telling the story, then this is my truth and my art."

Lakin Ogunbanwo's Portraits will run from November 20 at Rooke and Van Wyk, Unit 21, Frost Street Lofts, Braamfontein Werf, Johannesburg