On balance, it is a strange place to mourn Nelson Mandela, but in a country marked by so many unresolved contradictions, Nelson Mandela Square, a privately owned public piazza in the upmarket business suburb of Sandton, is both a fitting and an unavoidable choice of venue.

One of 150 public memorial areas hastily designated nationally to cater for the massive outpouring of grief, solidarity and respect in the wake of Mandela's death, the square is known for its landmark 6m-high bronze likeness of the boy from Mvezo in the Eastern Cape who became a statesman. At its unveiling in April 2004, television celebrity and businesswoman Basetsana Kumalo described the sculpture that dominates the square as "a very happy statue". It is hard to contest this interpretation, given the display of emotion enacted in front of the work in recent days.

Similar scenes of wreath-laying and prayer have also played out in front of sculptures depicting Mandela on Parliament Square in central London and Nobel Square at Cape Town's V&A Waterfront.

The squat figure of Mandela in Cape Town is the work of Claudette Schreuders, an artist whose intimate, family-focused art was indelibly shaped by the early days after apartheid. She is married to Anton Kannemeyer, the scabrous comic-book satirist and co-founder, with Conrad Botes, of Bitterkomix. For all their obsessions with genitalia and Afrikaner guilt, it was Botes who in 1995 produced an illustration of a flying Mandela in a superhero costume with the word "Madibaman" emblazoned above him.

The statue of Nelson Mandela in Sandton's Mandela Square (Carl de Souza, AFP)

The statue of Nelson Mandela in Sandton's Mandela Square (Carl de Souza, AFP)

A soulless statue

By comparison, the outsize work on Mandela Square possesses all the hallmarks of an older, more stolid approach to remembrance and place-making. Produced by sculptor Kobus Hattingh, an artist who established his name designing and manufacturing badges, crests and statues for the apartheid military and police, the Mandela Square sculpture, with its poorly resolved optical geo-metries, weighs only a little less than a Hummer and, as an artistic statement, is about as limber.

"I would take a bulldozer to that place," Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian literary titan and Nobel laureate, remarked during a Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) memorial lecture devoted to Mandela in 2005 where Cornell West and Henry Louis Gates also spoke. His statement was met with resounding applause.

The comment does not appear in the printed version of Soyinka's essay, which was edited by Xolela Mangcu in his then capacity as executive director of the HSRC's society, culture and identity research programme. This is not to mean that Mangcu declawed the critic. In the published version of his lecture, Soyinka, who claimed to have seen more than 100 figurative representations of Mandela – "all inspired by love, veneration, fantasy, canonisation, wish fulfilment, etc" – dismissed the Mandela Square sculpture as "soulless" and "truly horrendous".

He also warned against exaggerating the statesman's significance.

"The world already knows what he is, and indeed our greatest task these days is to maintain a sense of proportion and avoid further banalising a symbol that is already stretched to an almost inhuman dimension," Soyinka wrote. In 1988, he published the book of poems Mandela's Earth.

This lecture, which was delivered not long after the controversy surrounding a series of artworks attributed to Mandela, offers a useful point of entry for anyone curious about the brash iconisation and branding of the Mandela legacy.

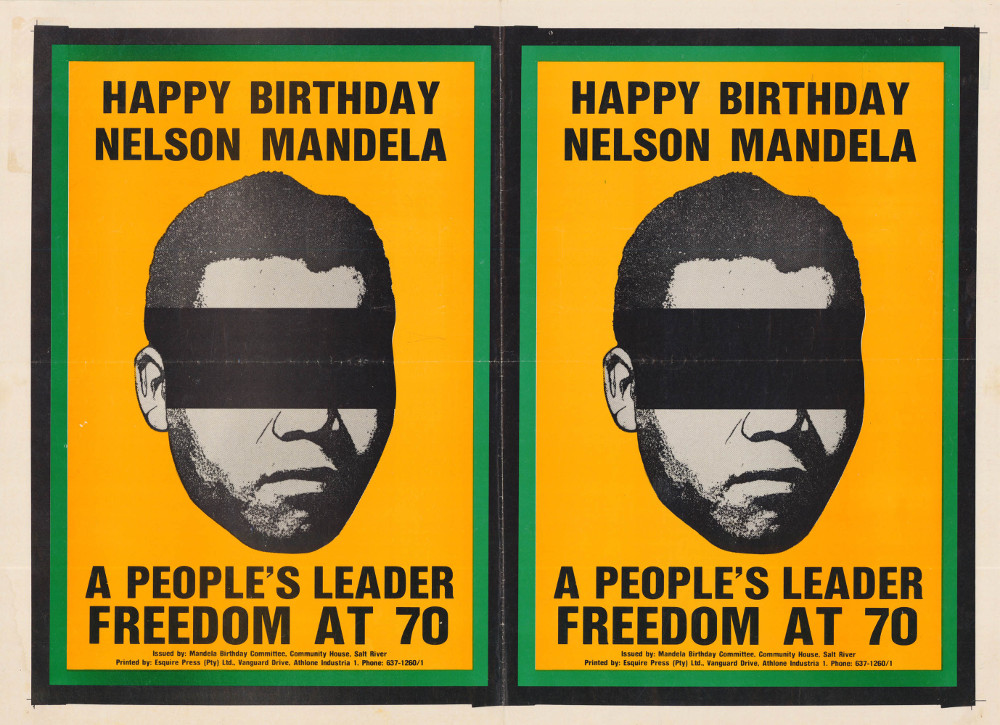

A censored poster for Mandela's birthday celebration

A censored poster for Mandela's birthday celebration

More than just a captive struggle icon

In 1988, when artworks by American graffiti artist and painter Keith Haring and Namibian printmaker John Muafangejo flanked the stage at birthday celebrations for Mandela at Wembley Stadium, wrote Soyinka, "he was already being appropriated as a symbol or a coat hanger for myriad pursuits, hopes, frustrations, ambitions, visionary projections and mundane preoccupations".

Long an invisible presence in South African political life, his image banned and censored, it is not uncommon these days to see Mandela's face adorning such unconnected and trite objects as fridge magnets, clocks and bar mats. The story of how this came to pass is intimately linked to Mandela's biography, which in purely visual terms oscillates between moments of intense, blinding presence and censorial invisibility.

Particularly during the years before his release from prison in 1990, as he transformed in the public imagination from a waggish lawyer with parted hair into a dapper civil rights leader and then captive struggle icon, Mandela moved in and out of sharp focus. Before his arrest in August 1962, while on the run from state authorities, Mandela would often disguise himself.

"My most frequent disguise was as a chauffeur, chef or 'garden boy'," the so-called Black Pimpernel writes in Long Walk to Freedom, his sometimes unreflexive autobiography published in 1994. "As a leader, one often seeks prominence; as an outlaw, the opposite is true."

During his subsequent imprisonment, Mandela's image was censored. Images of the robust, lightly bearded man recorded with such clarity in photographs by Peter Magubane, Jürgen Schadeberg and Eli Weinberg were purged from public life.

In 1986, 22 years after being imprisoned, an undated photo taken by the Department of Prisons appeared in a Bureau for Information booklet. Sporting a combed path and paisley tie, the photo was reprinted on the front page of Mail & Guardian with the headline, "The first legal photo of Nelson Mandela in 22 years". The photo revealed no hints of grey.

Though the general image oblivion that characterised Mandela's years in prison did nothing to deflate his power in the popular imagination it did result in some rather dodgy graphic renderings of the man, particularly in Latin America, it would seem.

Drawing on hopelessly outdated, often second-hand images, poster-makers and designers globally were forced to come up with inventive solutions using the bare minimum. This is perhaps the most endearing quality to the many struggle-era depictions of Mandela: the way they balance pure invention with a principled fidelity to a faded, out-of-date photograph of a man languishing on an island in clear view of his white masters.

Nobel Square at Cape Town's V&A Waterfront

Nobel Square at Cape Town's V&A Waterfront

Contemporary images of Mandela after 1990

Mandela's visual indeterminacy reached its apogee shortly before his release. In 1989, trade union federation Cosatu audaciously released an offset litho poster offering a contemporary rendering of Mandela, a colour drawing by an unknown Dutch artist produced entirely from verbal accounts of people who had seen him in prison.

Highlighting the extent of the annihilation of Mandela's image during his captivity, when it was announced that he would be released from prison, the po-faced subject in the Cosatu poster appeared on the cover of the Argus. For desperate picture editors announcing the big news of Mandela's release and the unbanning of the ANC, there was quite simply nothing else to work with – nothing contemporary, at least.

Time magazine also opted for an impressionistic drawing of Mandela, although their graphic artist seemingly had Sidney Poitier in mind, not Mandela. City Press led with a vintage pre-prison photograph of Mandela embracing his former wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, while the Mail & Guardian, having a week's grace following Mandela's Sunday release, ran with a black and white photograph of a grey man in a suit.

Mail & Guardian cartoonist Derek Bauer portrayed Mandela on numerous occasions. A skilled graphic artist indebted to the wildly expressive and sardonic style of Ralph Steadman, Bauer's renderings of Mandela were for the most part descriptive, more sociological than satirical. Bauer's general distrust of politics was tempered in the case of Mandela and his Nobel Peace Prize co-recipient, FW de Klerk.

"Mandela and De Klerk I respect," he wrote in 1992. "Mandela for persistently believing he was right against all odds and De Klerk for facing the truth. But as politicians, I don't trust either of them."

This respect, if not faith, established an important precedent, one that has rarely been deviated from since.

"Certainly the reverence with which Mandela is regarded, even by hard-bitten hack cartoonists, is extraordinary," observed journalist Karen Rutter in 2000 on the prevailing tone of cartoons depicting Mandela in the years following his release. Even Jonathan "Zapiro" Shapiro, whose Mandela archive is extensive, pointed to only one vaguely ambiguous cartoon of the deceased statesman when I spoke to him.

In the fine arts, Mandela's image has also served as a popular reference point. Works by well-known artists Willie Bester, Wayne Barker and sculptor Johannes Segogela, who in 1996 portrayed Mandela with the South African football squad, are all unflinchingly reverential. Much in the manner of Schreuders's sculpture, one of four depicting local peace icons, these artists inhabit the age-old role of artist as praise singer of the new state.

Prisoner No.466/64 (?Artist Lisa Brice)

Prisoner No.466/64 (?Artist Lisa Brice)

There is nothing insidious about any of this: some of Russia's finest creative accomplishments are those of artists who, in 1917, allied their creative enterprise with the revolution. What came after was unknowable.

Of the more interpretive artworks to engage Mandela, Lisa Brice's Prisoner No. 466/64, exhibited on Robben Island in 1997, is a thoughtful, if not necessarily visually exciting, meditation on Mandela's incomplete visual identity. In an attempt to reconstruct Mandela's lost identity from his prison years, Brice asked police forensics experts to create an image of Mandela in prison using photographs of him before and after his confinement. The reconstructions that resulted were inconclusive, something the artist tendered as a comment on the quest itself.

The visual hole presented by Mandela's missing years in prison has, to some extent, been plugged by the activities of the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, an organisation established to honour and document the statesman's life. In 2005 it hosted an exhibition that included rare prison photographs. An image showing Mandela in horn-rimmed sunglasses and a hat caught the public imagination; it was quickly pirated and turned into a T-shirt emblem.

Mandela's passage from liberation hero to icon is not unusual; it has precedents elsewhere. Nor is the process whereby his self-image has become abstracted from his life story exceptional.

"Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation," cynically asserted the Marxist intellectual Guy Debord in 1967, long before the advent of Google and its offering of 2.8-million search results responding to Mandela's name.

Despite the surfeit of contradictory images we now associate with his name, what remains truly extraordinary is Nelson Mandela's durability as a visual icon. The assaults of pernickety censors, ropey artists and avaricious businesspeople may have tarnished its value somewhat, but ultimately, the munificence and light Mandela embodies, as a person who lived, continues to prosper, undiminished.