Glencore Xstrata chief executive Ivan Glasenberg received

You probably don't know it, but almost everyday is a Glencore Xstrata day.

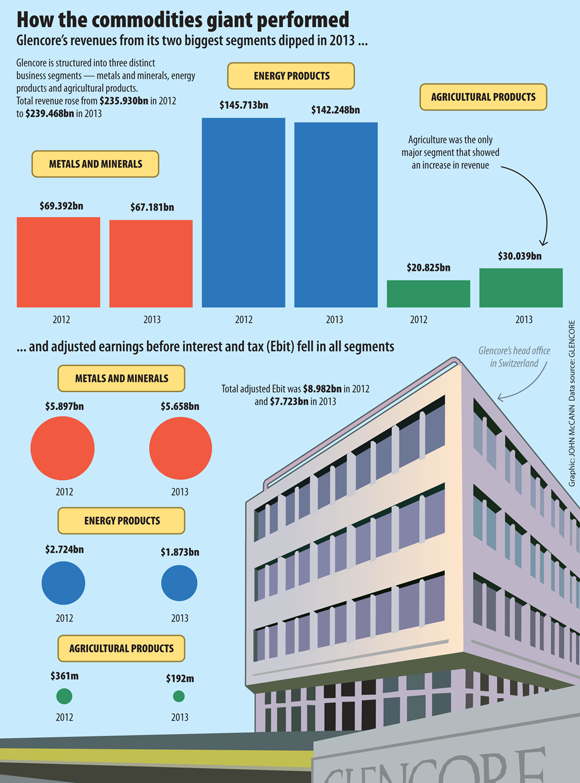

With global sales of $239-billion last year, as reported in its 2013 annual report released on March 18, the commodities colossus straddles markets from chrome and copper to cotton and corn. Its reach is so pervasive that it's quite likely that the appliances you use or food items you consume each day have in some way been touched by Glencore Xstrata.

The company, based in the low-tax jurisdiction of Switzerland, made collective dividend payments to its seven directors, the largest shareholders, of $500-million during the past financial year.

Johannesburg-born Ivan Glasenberg, the Glencore Xstrata chief executive who owns 8.4%, the largest share of the company, received dividend payments of $173-million in 2012 and $182-million last year.

When Glencore listed in 2011 it was owned by just 480 people, all employees. The company, which operates in 50 countries, emerged from obscurity in 2011 when Glencore first listed on the London Stock Exchange. In 2013 it merged with Xstrata in the largest takeover ever seen in the mining industry, at a cost of $46?billion. When it listed on the JSE in November 2013, it was instantly the third largest listing.

Although it had previously enjoyed privacy as an unlisted entity, Glencore was notorious for questionable business practices tracing back to its founder and the subject of one of the largest tax evasion cases in United States history, Marc Rich.

"Before these guys listed, even if half the stories going around were true, many were a bit scary," said Peter Major, a fund manager and analyst at Cadiz Corporate Solutions.

The company has struggled to shake off the resulting bad reputation and it is not helped by controversies that are continually highlighted by nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and the media.

These include allegations of tax evasion and pollution in Zambia, breaching international child labour law and dumping raw acid in a local river in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). It has also been accused of human rights violations in the Philippines and Peru. The company has denied the claims, describing some as "unfounded" and "libellous".

Now with its financials in the public eye and a global focus on tax justice, especially for the extractive industries, Glencore Xstrata has become enemy number one as far as some NGOs are concerned.

The company pays a lower average tax rate than some of its competitors – 20% versus an average of 33% for the major resources companies. This is partly a result of being headquartered in Switzerland (as it has been for 40 years) and partly because of its business mix – marketing activities attract a much lower tax rate than industrial activities alone.

Thembinkosi Mfundo Dlamini, the governance manager at Oxfam, said it is worth noting that Switzerland is a "tax haven" used by corporate companies, particularly those dealing in resources.

"It is for sovereign-backed secrecy in terms of critical legal and financial activities that do not allow for exchange of information or provision of harmful corporate vehicles, among other perks," Dlamini said. "Tax holidays may be available in certain cantons for up to 10 years. Effective tax rates can be reduced to 5%, depending on whether the company qualifies as a holding or principal company. But, most importantly, manufacturing artificial losses is possible when conducting corporate activities in tax havens. This means that taxation owed to South Africa may be reduced through non-actual costs."

In 2011 a group of NGOs commissioned a draft desktop study by Grant Thornton, which found tax avoidance by Glencore in Zambia to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars. As a result, the European Investment Bank froze all loans to the company and its subsidiaries, citing serious concerns about corporate governance, and subsequently launched its own probe into the company.

Glencore has questioned this study and says it has been cleared by the Zambian tax authorities. The bank said its freeze remains in place, but the Zambian Revenue Authority could not comment on the current position.

The company has its supporters as well as its detractors. "Most of the NGOs don't understand what they are talking about," said Paul Gait, senior research analyst at Bernstein Investment Research and Management. "These guys pay a huge amount of tax, both in terms of directly to government [and] in terms of payroll contributions … It's simply not the case that they are reaping the benefits of someone else's resource base. There would be no value in these deposits had they not been investing in developing the resource base," he said.

"Should [Glencore Xstrata] take Anglo, it would become the biggest mining company in the world"

Xstrata said its combined companies paid more than $4.3-billion in royalties and taxes and it has profit-sharing or other financial agreements in place. As heavily invested as the directors are in the company, and being listed to boot, they have been working to clean up their corporate image and grow their market valuation, Major said.

Glencore Xstrata, with a market capitalisation of around $70-billion, is somewhat behind that of resources leader Rio Tinto with $83-billion, just ahead of BHP Billiton's $64-billion and considerably ahead of Anglo American's $34-billion. Anglo is seen as a likely future takeover target for Glencore Xstrata, although the company has refused to speculate on possible acquisitions.

David van Wyk, lead researcher at the Bench Marks Foundation, which has been looking into companies such as Glencore since 2001, did fieldwork in the DRC as part of a published report on Glencore titled Contracts, Human Rights and Taxation: How a Company Exploits a Country.

"If Glencore realises its dream of taking over Anglo, South Africa would be in Glasenberg's pocket. Should it take Anglo, it would become the biggest mining company in the world," said Van Wyk. "We have copies of Senate reports from the US that express concern about the monopolistic nature of Glencore."

Glencore Xstrata is more vertically integrated than other resources companies — being active in upstream mining and resource extraction as well as downstream marketing. Its marketing and logistics activities mean the company has the advantage of strategic intelligence and the ability to understand the cycle and underlying supply and demand issues.

"The vision is one of a large number of people on the ground collecting real-time info from the market," said Gait. "Presumably, this means it can respond to changes in the market faster than other mining companies [can]."

And it's this advantage that saw Eskom trying to block the merger between Glencore and Xstrata in early 2013 when, in a confidential last-minute submission, of which the Mail & Guardian has a copy, the parastatal detailed pressing concerns about the merged Glencore Xstrata's ability to influence domestic coal prices and take advantage of the utility's supply shortfalls. It claimed the company's "endgame" was to introduce an export market-related price factor for coal.

But on the day it was meant to make its case at the Competition Tribunal, Eskom met with Glencore behind closed doors and suddenly withdrew its objection. A memorandum of understanding was drawn up and both parties refuse to divulge details of the agreement.

"You can bet their endgame is export parity prices in South Africa. All coal producers in South Africa have an 'endgames' target of export parity pricing," said Major. "Eskom is terrified because they know it's coming."

But Glencore group executive Clinton Ephron recently commented, as reported by Business Day, that the company believes it still has some space left to explore mergers and acquisitions relating to South African coal before competition authorities might block them. Its shareholding in the Richards Bay terminal is not nearly as high as that of some previous shareholders, he said, and does not account for even one-fifth of Eskom's coal supply.

Glencore Xstrata's latest results, as detailed in the company's annual report, showed strong financials driven by aggressive cost-cutting measures. Adjusted net income was at $3.7-billion. It says it expects acquisition synergies following the takeover of Xstrata to amount to $2.4-billion a

In its report, the company said it intends to "pursue a progressive dividend policy with the intention of maintaining or increasing its total ordinary dividend each year".

Major said: "Ivan would lure in a lot more investors by paying higher-than-industry dividends for a few years. He wants to stand out from the other mining companies in many ways."