As business and civic leaders picked at their fruit bowls in the Sandton Convention Centre on Tuesday morning, Trade and Industry Minister Rob Davies highlighted the extent of inequality between rich and poor in South Africa.

There are "super salaries at the top, and very meagre livelihoods at the bottom," said Davies.

In 2012, "the highest-paid chief executive earned 51 000 times what someone earns on the child support programme. That's the level of in-equality that we have in South Africa."

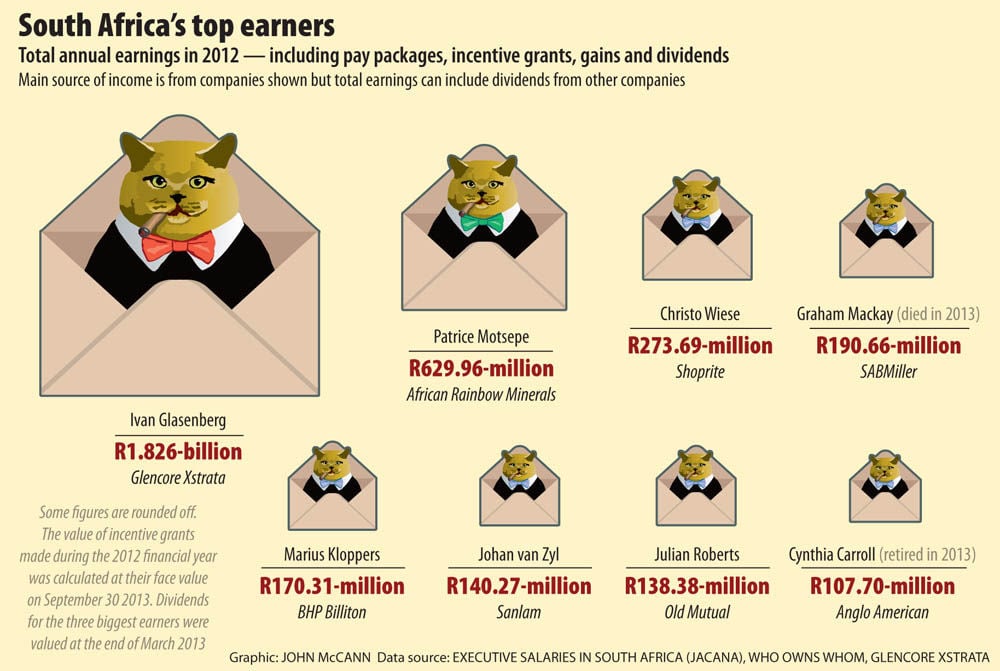

The disparity highlighted by this figure is astounding, and yet the calculations determining the biggest salary – which was R190.7-million, awarded to Graham Mackay, then still the chief executive of SABMiller – still do not fully represent the exorbitant incomes of some of our biggest earners.

Executives who play a role in listed companies and own numerous shares in the same entities not only walk away with top-tier salaries, but also compound their earnings with dividend payouts.

True chasm

Dividend payouts are not generally included when calculating an executive's earnings, but doing so gives a more accurate picture of the true chasm between South Africa's richest of the rich and its poverty-stricken.

Calculations that include dividend payouts, provided by independent research organisation Who Owns Whom, show a trebling of top earnings in South Africa.

The biggest South African earner in 2012 was Glencore Xtrata's chief executive, Ivan Glasenberg. The billionaire drew a comparatively modest salary of $1.5-million (R15.6-million). But he took home dividends of $173-million (R1.8-billion), thanks to earnings the commodities giant made from listings abroad.

Glasenberg is followed by Patrice Motsepe, whose take-home earnings, including salary and dividends, were R630-million. His salary made up R11.06-million of that, and R618.9-million was thanks to dividends paid out on shares he and his family own in two largely South African companies: African Rainbow Minerals and Sanlam.

In 2010, Shoprite's chief executive Whitey Basson took home R627.5-million. His salary and benefits constituted only R33.1-million of that amount; the almost R600-million remaining was thanks to his decision to exercise a vast swathe of share options.

Glasenberg's R1.8-billion would be 486 000 times that of the earnings of one with a child support grant; Motsepe's two-thirds of a billion rand would be 168 000 times that.

Rising inequality is coming under increasing scrutiny around the globe. This year's meeting of economic leaders in Davos put the spotlight on an Oxfam report that claimed the world's richest 85 people controlled the same amount of wealth as its poorest 3.5-billion people.

In his recently published book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French economist Thomas Piketty draws on extensive research to argue that the main factor driving inequality in the United States is the exorbitant salaries large companies award their top executives.

Piketty says that "supermanagers" account for up to 70% of the top 0.1% of the income distribution in the US, a group that earns at least $1.5-million (R15.6-million) each annually.

"The law is simple," writes the New Yorker's John Cassidy in his review of the book. "When the rate of return on capital – the annual income it generates divided by its market value – is higher than the economy's growth rate, capital income will tend to rise faster than wages and salaries, which rarely grow faster than gross domestic product."

So, earnings in the form of dividends, rents and vested share options are likely to accumulate at a rate much higher than a person who does not own capital is able to increase their salary.

Astronomical earnings

The astronomical earnings of South Africa's business elite are largely attributable to these forms of capital, rather than the executives' guaranteed package.

Business mogul Christo Wiese, who holds director and chairperson positions in five listed companies in which he owns shares, took home a R8.69-million combined salary from his duties in 2012. But, according to the Who Owns Whom calculations, dividends from his various shares in Shoprite, Brait, Invicta and Tradehold earned him another R265-million.

Naspers's Koos Bekker is lauded in some circles for taking home no salary at all. But, as observed by the authors of Executive Salaries in South Africa: Who Should Have a Say on Pay?, the media boss is actually earning a colossal amount.

"One would think from looking only at the cash and benefits package of Bekker that he is working for free," they write. "However, when the value of long-term investments vested during the year is included in the calculation of his package, the amount of money he received during 2012 is astronomical. The pretax face value of [Bekker's] options that vested in 2012 alone was over R1-billion on the date of vesting."

"If we are to reduce inequality in South Africa, we must shift the balance of opportunity towards those for whom work, regular income, decent shelter and adequate nutrition are still aspirations," said Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan in his foreword to the book.

The private sector had a "big role to play" in this, Gordhan said. "Rather than rely on economic rent and endeavouring to accumulate the bulk of the rewards of improved productivity … the private sector should embrace entrepreneurship, innovation and an equitable sharing of the fruits of prosperity."

What you see is not what an executive gets

Although it is a reporting requirement for listed companies, many people are unaware of how much money is transferred into the well-fed bank accounts of the country's most senior executives.

In their book, Executive Salaries in South Africa: Who Should Have a Say on Pay?, Kaylan Massie, Debbie Collier and Ann Crotty give a breakdown of how the average executive is paid.

In addition to a cash and benefit package, executives make gains by exercising or vesting short and long-term incentives (LTIs). These gains in one year alone "can reach two to three times the cash and benefits package", the authors say.

Companies are often vague about disclosing the LTIs granted to an executive, the researchers say. "Typically, the value of LTIs granted during the year is not included in calculating an executive's pay package. This omission is to the detriment of shareholders and others in the public, who are left in the dark as to the actual value … provided.

"A shareholder will have no idea what value these LTIs have been until three or five years later. At that point, it is too late for [them] to voice their concern about the grants being made."

A typical executive's pay cheque includes the following:

- Guaranteed package: It usually consists of the annual salary, company pension contributions, medical benefits and allowances, for example, housing and vehicle allowances.

- Short-term incentives (STIs): They are usually paid every year and linked to the executive's individual performance or the company's performance during the year. If targets are not met, the STIs will not be paid. They usually come as a cash bonus.

- LTIs: These are cash-based or equity-based incentives. Some LTIs are performance based, others are unconditional or granted as "retention". LTIs usually vest between one and five years after conditions have been met. The executive can then sell, transfer or exercise the stock option (pay the strike price in return for a full share in the company).

- Dividends: Although this is not part of the official pay package, many executives are shareholders in the companies they run. Dividends are payouts given by a company to its shareholders out of its profits or reserves.