Seventy-year-old Elizabeth Barnes wakes up at 2am, unable to breathe. The retired nurse, a resident of South Durban, gets up and, wheezing, draws a little air into her lungs. Her room is stuffy. She opens a creaky white door and goes into the narrow passage, looking for fresh air. The air is filled with black dust. This usually happens when the nearby refineries burn off excess gas.

Reaching for her old Nokia, she phones for an ambulance, which arrives 15 minutes later. In hospital she is put on a nebuliser, which releases a mist that works its way into her lungs and reopens them.

“That black snow is like Doom. It kills everyone,” says Barnes.

She gets worked up when she talks about that night, and similar nights during the three decades she has lived in the area. On her worst day, last year, the ambulance was called three times.

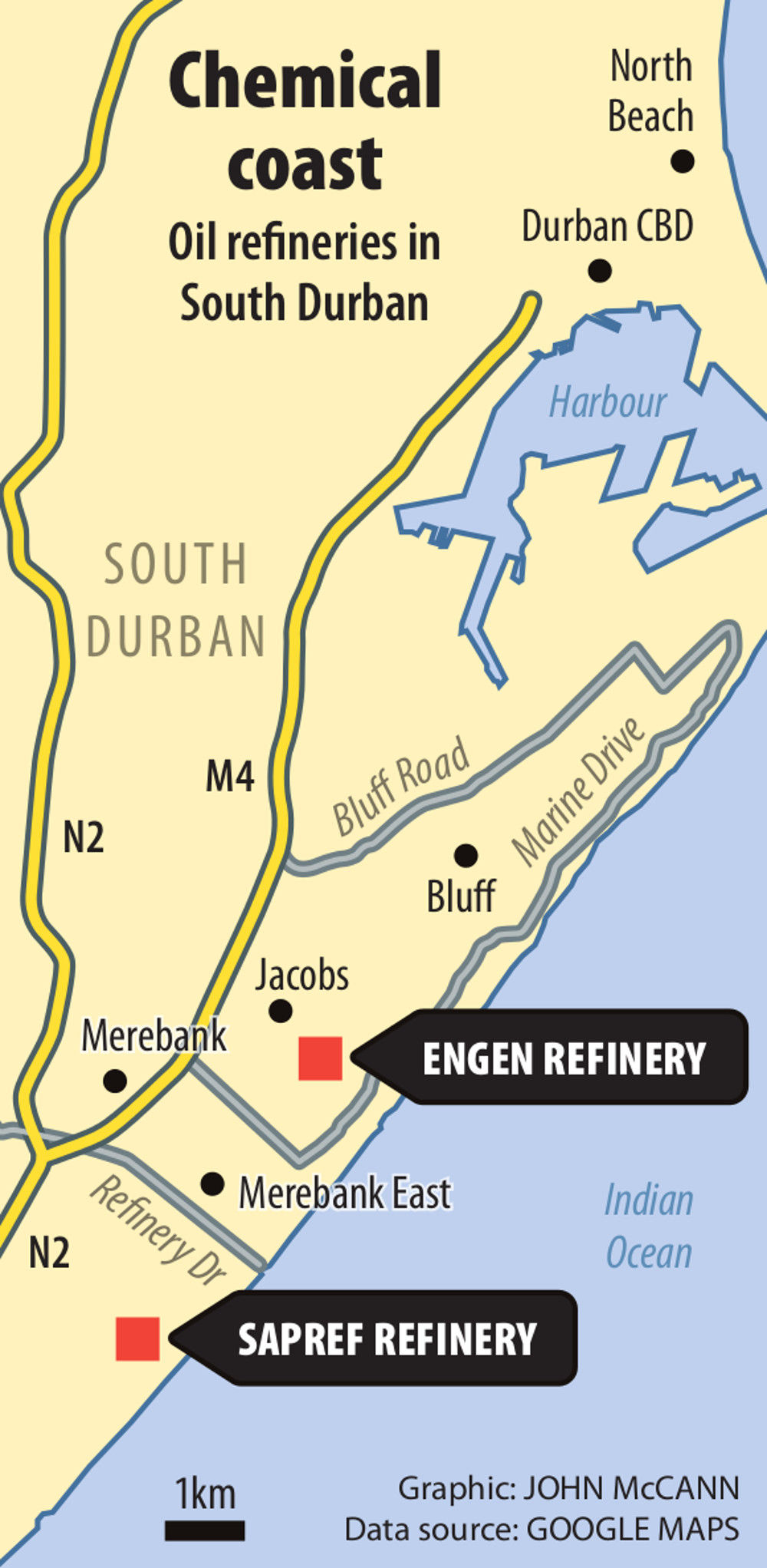

Sitting on a black faux-leather couch and dressed in a black dress with white polka dots, she gesticulates energetically as she rages about the nearby Engen refinery. She is one of 100?000 people who live in the area, where gases from industry are funnelled between two ridges that run from north to south. To the north is Durban harbour and beyond that the buildings along the beachfront and central Durban.

Cancer valley

Cancer rates are so high that everyone speaks about it as “cancer valley”. Research by the University of KwaZulu-Natal shows that leukaemia is 24 times higher here than anywhere else in the country. Half the schoolchildren in the area suffer from asthma.

The two largest industries are the oil refineries, but the presence of many other petrochemical plants means there are about 300 smokestacks in South Durban.

Barnes used to be fit. She grew up on a farm and had a 15km walk to school every day. A dozen people rent rooms in her haphazardly extended home. Two died from skin cancer last year. She feels responsible for her tenants and now has trouble sleeping, waiting for one of the tenant’s children to gasp for breath.

A white, worn asthma pump becomes a conversation prop. “This is my gun. It shoots air into my chest.”

Elizabeth Barnes suffers from chronic asthma and relies on her inhaler. She developed the disease when she moved to Jacobs. (Photos: Delwyn Verasamy)

Before 1938, South Durban was farmland but the city council rezoned it as a mixed industrial and black residential area. People were moved in to provide cheap labour. Industry boomed and now 70% of the city’s factories are here. Oil tankers bring 80% of the country’s crude oil to a mooring buoy 2km off the coast.

Refining zone

The 60-year-old Engen refinery and the 50-year-old Sapref refinery (owned by Shell and BP) process this oil into petrol, diesel and paraffin. Other industries that rely on petrochemicals, such as plastics and benzene manufacturing, have opened around them.

The city’s air quality records show that over 100 different chemicals are pumped into the air. The worst are sulphur dioxide and benzene, which the World Health Organisation says causes asthma, cardiopulmonary disease and cancer.

The refineries have said the high level of illness in the area is a coincidence and none has been convicted of causing illness there.

Most of the residents live in small homes and crumbling blocks of flats. In one of these, Maygen Lee Reddy, a 12-year-old in grade seven at Settler’s Primary School, is one of the seemingly lucky few because her father bought an old and faded portable nebuliser. She says she had an asthma attack the night before and could not go to school. She misses up to 10 days a month.

Perumal Puckree helps his granddaughter Maygen Lee Reddy with her nebuliser.

The Reddys live south of the Engen refinery and north of Sapref, in the mostly Indian neighbourhood of Merebank. The area is divided by race. To the west, where Barnes lives, is the mostly coloured neighbourhood of Jacobs. To the north, on hills overlooking the ocean, is the mainly white neighbourhood of the Bluff. The closer you get to the refineries, the stronger the smell. In Merebank and Jacobs, there is an ever-present smell of rotten egg.

Quality of life

South Africa’s submission in 2005 to the United Nations environment agency on air quality said the area is “overwhelmed” by petrochemical companies and that the situation has “undermined the quality of life of residents in the area”. This added to the burden of disease, it said.

Other research published in the peer-reviewed African Journal of Conflict Resolution said: “[The effects of air pollution on human health] are caused by the emissions of unacceptable levels of toxins, chemical waste and a large content of sulphur dioxide, which are characteristic of industrial processes.”

Sylvie Chetty, a slightly built woman in her 50s, lets as little air as possible into her flat, which is in the same block as that of the Reddys. All the windows are closed and the second-floor flat is hot and stuffy. Like all those around her, the block has seen better days.

“We moved here 25 years ago and we started having problems straight away,” she says.

The 3m-high vibracrete wall of the refinery is 400m down the tar road that runs past her home. Her husband worked as a bookkeeper and died from a heart attack five years ago. His asthma was so bad that he had to stop after each step leading to their four-room home.

‘Trusting in Jesus’

Deeply religious, like many people in the area, she says: “I am trusting in Jesus to keep my chest going.”

Curtains act as room dividers. She replaced these after they were stained black by the fallout from an explosion at the Engen plant in 2011. The company gave Chetty and her neighbours R500 each for their curtains and clothes, the only compensation they say they have ever received.

She says most people seem to have asthma and is in no doubt about who is to blame. “At Engen, they are clever. They make all the money but they don’t share it. I just want some so I can go to hospital and be cured.”

A clock emblazoned with a painting of Jesus ticks loudly on the wall. She has a doctor’s appointment, and shows us her bag of asthma medication and a piece of paper with her four monthly visits noted down.

Her neighbour, Sharon Eyer, slides back the heavy black bolt of her security gate, saying violent drug gangs are a serious problem. The room is crowded with a three-piece couch set and a cabinet covered in family pictures. She is also a widow and a black-and-white photograph of her husband in his 20s, sporting a thick beard, takes pride of place. A single bulb lights the dingy room.

Forced to quit work

The family was once middle class but her husband, a construction worker, was forced to quit because of his asthma and they slipped down the economic ladder. Now they live in a government flat. At 59, she cannot get a job and her asthma medication costs R400 a month.

“Sometimes you are so sick that you cannot breathe. How do you make it to a taxi when you are like that?”

Her 23-year-old son, a cashier, is the sole breadwinner. But he has a worsening cough and misses several days of work every month.

Both the women have grandchildren living with them, some of whom also have asthma. Little research was done on the disease until 2001, when a large-scale study by the universities of KwaZulu-Natal and Michigan found that half of the children in the area had asthma. A follow-up study in 2005 found that people in North Durban were less likely to suffer from chest problems and cancer because of the lack of industry there. Children at South Durban schools were 40% more likely to suffer from respiratory problems than those living 10km away, it said.

Research published by the Medical Research Council on chronic respiratory diseases in South Africa found that environmental conditions are drivers of problems in low- to middle-income areas. This explained the “very high respiratory symptom prevalence” in South Durban.

Chest problems

The various parts of the health department refer questions to each other, but a doctor in the community says treating chest problems takes up a large part of every day. It is also expensive, because patients require constant medication and consultations, as well as emergency treatment and hospitalisation.

People with cancer are also a disproportionate health burden, with many not having the money to access more advanced treatment such as chemotherapy, the doctor says.

The refinery fence is also visible from the office of Dale Sidle, headmaster of Merebank Secondary School. He says asthma is a chronic problem, but there is little he can do about it. By law, he cannot administer medication such as asthma pumps, so must rely on children to have their own. The problem is worst during exams, when stress triggers attacks.

“The plants are so old that they are just putting plaster on the cracks to keep them going,” he says.

Nielsen Singh joined the army as a physical education trainer and, now in his 70s, volunteers to help pupils at local schools.

He was at Settler’s Primary School when oil flung from a refinery explosion caused 100 pupils to be hospitalised. “It was awful. They were screaming and running around, rubbing their skin.”

Children suffering

A slow and patient speaker, he says it is difficult to coach the children because of the health problems. “This is one of the most polluted areas in the world and you see it in the children. They struggle to run as fast as they should at their age. Many have their pumps always there.”

Physical education trainer Nielsen Singh says the children’s development is being retarded.

Professor Patrick Bond arrives at a bar on the beachfront for an interview wearing a formal shirt, but with flip-flops and swimming trunks. A political economist at the school of development studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, he lives on the Bluff.

He says of the neighbouring communities: “This is environmental racism, by smell.” He says the refineries are “rust buckets” and should have been closed a long time ago. That this has not happened can be put down to a weak government and strong corporate interests, he claims.

“People are sick and tired of being polluted on because of the colour of their skin.”

The area’s Democratic Alliance ward councillor, Aubrey Snyman, says it is hard to link specific health problems to industry. “There is no way to take the research and sue,” he says. Therefore, the onus is on the government to keep ensuring that business lowers its emissions.

Former runner

He says he grew up in the area and used to be a runner. Back then, the Engen plant was owned by Mobil and there was a layer of dirty air hanging over the valley. “Back then we would gasp for breath but we just thought we were not fit enough.”

Awareness about the impacts of industry on air quality and health only started becoming prevalent in the 1990s. His daughter of eight has asthma but, with a healthy diet and medication, he hopes she will grow out of it.

The hub of local activism is the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance, which is run out of four rooms in a house in Jacobs, crammed from floor to ceiling with folders of evidence about local pollution. A minibus is parked outside from which the alliance conducts what it calls “toxic tours” for visitors and locals.

Desmond D’Sa, a founder of the alliance, has just returned from collecting the Goldman Prize in the United States. The world’s most prestigious accolade for environmental activism, it is worth $150?000 and was awarded for his work on pollution in South Durban.

Environmental activist Desmond D’Sa says the refineries can no longer claim that there is no link to the health problems of the communities.

He says the oil and petrochemical industry believes it is above the law and is “using our lungs as purifiers”.

“There is a R40-million daily profit from industry in this area, but we are the ones carrying the health costs.”

Air quality report

The eThekwini municipality’s air quality monitoring report from 2008 says the average levels of sulphur dioxide are within guidelines. In South Africa, refineries can emit 19 tonnes a day although in Europe the limit is two tonnes.

The report concluded that, because of the correlation between wind direction and cases of air pollution picked up by monitoring stations, industry is the major culprit. In 2007, it said 39 out of the 41 times that maximum emission levels were exceeded could be “directly attributed” to Engen, with Sapref and other petrochemical firms playing a lesser role.

But the refineries are critical to South Africa and both are national key points. Besides air quality issues, they have caused other environmental problems. Between 1995 and 2010, 12 explosions were recorded. In 2001, a million litres of petrol leached under people’s homes, thanks to a rusting Sapref pipeline leaking. It says it has since improved its pipelines and checks them annually for any possible problems.

But the refineries say that the link between their activities and health problems cannot be proved and that they have significantly lowered emissions.

Gavin Smith, Engen’s spokesperson, says the refinery is committed to minimising its impact. It gives R5-million a year to community projects and has spent R700-million in the past 11 years on upgrades. It complies with its emissions permits and is also “ISO14001 certified” – which means the potential impacts of its operations are identified and mitigated.

Acceptable emissions limits

He says it has not put any pressure on the government to keep operating and has worked with the state to ensure its emissions are within acceptable limits.

He says tests on Engen’s own employees show “no indication of increased health issues”. “We are not aware of any definitive research linking the Engen refinery to respiratory disease and cancer,” he says, adding that, generally, cancer is increasing worldwide and about 250-million people have asthma.

He says the refinery has reduced its sulphur dioxide levels by over 70% in the past 13 years, and the emissions of this and other gases will be continually lowered in the coming years.

He adds that the early morning flaring is done “to combust gases safely should there be inefficiencies in the plant’s manufacturing processes”. Flyers are distributed to nearby homes and the flow is limited to prevent large flares.

But D’Sa says the defence used by the refineries – that there is no evidence linking them to community health problems – can no longer be used.

“The evidence is clear. This is 2014 and that argument does not work any more. We know these refineries kill people. We know it and they know it. They have blood on their hands. Our government lacks the political willpower” because, he maintains, the refineries generate huge revenues for the state.

The Mail & Guardian spoke to more than a dozen other families with asthma and cancer sufferers. Many also had relatives who died from complications arising from these diseases.