Nadine Gordimer in 1974.

My first clear memory of Nadine Gordimer was in 1960 during the first State of Emergency, when she came to the women’s prison at The Fort (now part of the Constitutional Court complex) to visit her friend, trade unionist Bettie du Toit.

I was 16 at the time and I was there to visit my mother, who was in detention with Bettie and others. As a child, I saw Nadine often because she was a friend of my parents. She sat through my father’s entire trial, so we also saw her then.

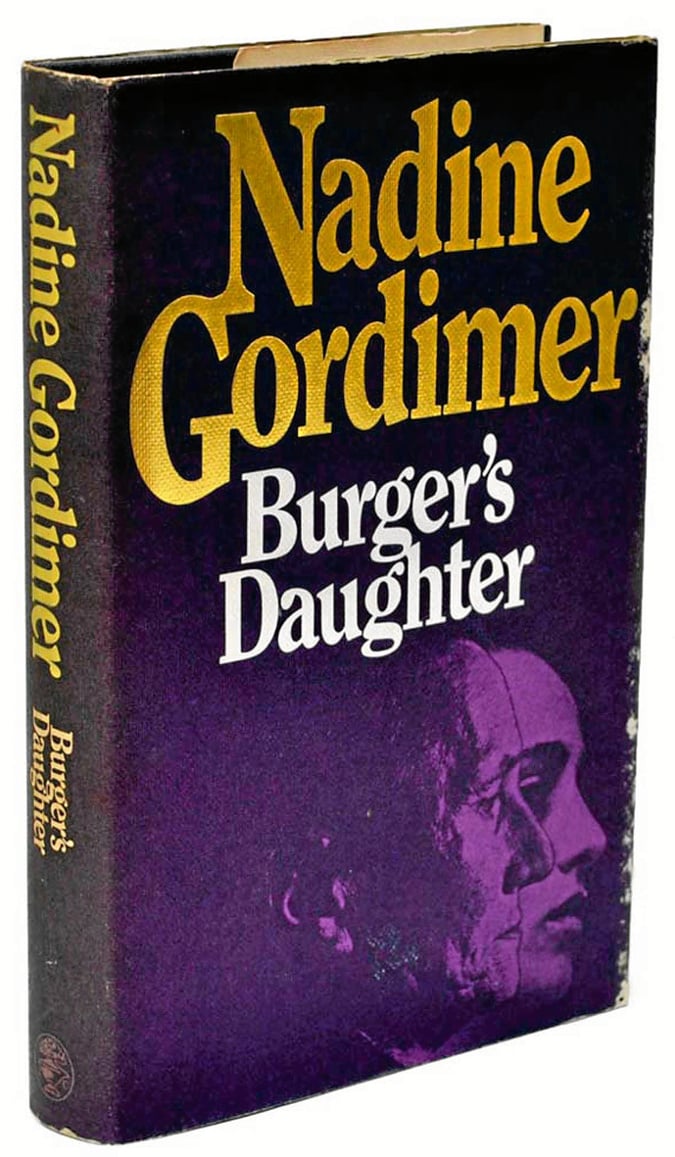

When she wrote Burger’s Daughter, she gave me the manuscript to read before the book was published. It’s not that she wanted my approval, but she knew that people would make the connection to my family and she wanted me to see it first.

In the letter that she sent with the manuscript she explained that she did not usually allow anyone but her publisher to see a manuscript before it was published, but she wanted me to see this one. She was anxious not to upset me. She said she had specifically not wanted to get to know me better before the writing of the book, because it was a novel.

A couple of weeks later, when I took back the box of papers that was the manuscript, I said to her: “You have captured the life that was ours.” She had the extraordinary ability to describe a situation and capture the lives of people she was not necessarily a part of.

No offence

All authors write of the circumstances around them, circumstances they are familiar with, and she did that very well. But, from reading the book I realised that the character was not me. Quite recently, when we had become close friends, she again checked with me that I had not been offended by the book.

As for her other works, I’m particularly fond of her short stories. I find her books not easy to read, but that is more my problem than hers. By “not easy to read” I mean they are very carefully structured and therefore need to be very carefully read. I am very fond of her short stories. They are extraordinary pieces of work.

llse Wilson at Bloemfontein Airport when its name was changed to Bram Fischer Airport in honour of her father. (Gallo)

Of late, we had been seeing each other a bit. We’d have dinner. She’d come to our house or my husband and I would go to hers, but it was Maureen Isaacson who really looked after her, walking her dogs and doing chores for her because Nadine’s children were overseas.

We were friends and in the last couple of months we were very close friends and spent a fair amount of time together, but Nadine was a private person. One didn’t just drop in; we’d phone and check up on her and she was always very welcoming.

I think that what she enjoyed about our company was that we didn’t treat her as someone on a pedestal, someone one had to defer to. We could tease her and joke with her and she enjoyed that.

Secrecy Bill

In the past few years she had been worried about where the country was going, and often said: “I wonder what Bram would have thought.” Her particular worries were the proposed Media Appeals Tribunal and the Protection of State Information Bill. There was an interview she gave recently to Carlos Amato of the Sunday Times in which she said she was shocked that an organisation she had supported would try to push through a Bill that “threatens to bring back one of the great features of apartheid”.

Burger’s Daughter fictionally reflects on Fischer’s family.

Her mind remained clear right until the end. Her commitment to the struggle was through her writing and her support for young writers. She had endless sessions with young people who wanted to write.

She was not a revolutionary in terms of taking up arms, but she was clear that she would not be silenced. She was aware that certain things in the country had improved enormously, but she was also clear that she wanted a better society.

We had been seeing her regularly until her children arrived to be with her in her last few weeks. We were saddened but not surprised by her passing. We cherish our memories of a great South African.

llse Wilson spoke to Kwanele Sosibo.