Opponents of Egypt's ousted president Mohammed Morsi protest in Tahrir Square on Friday.

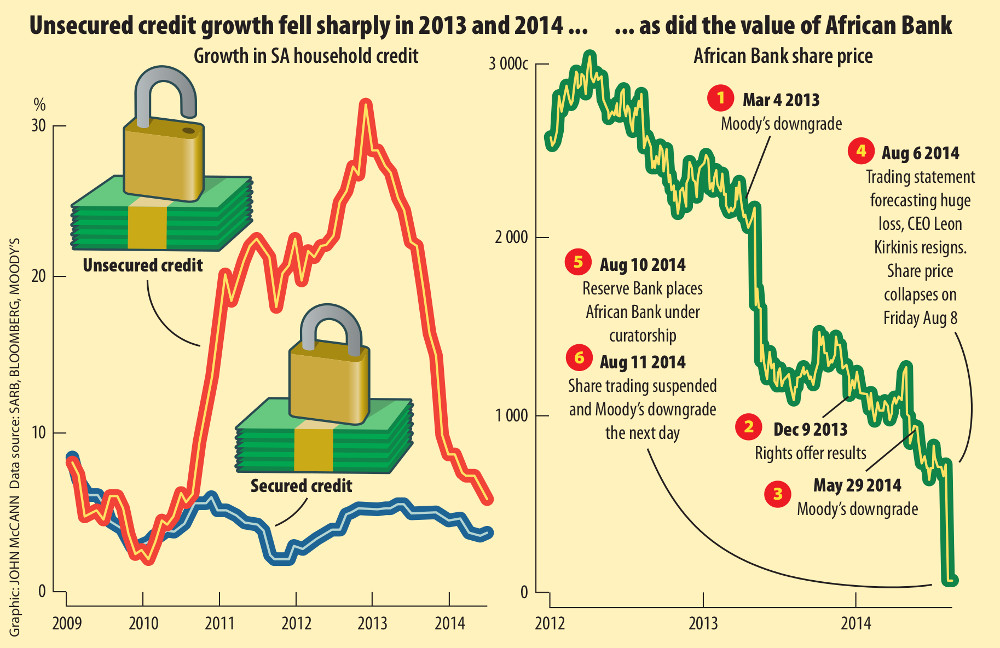

African Bank Investments Limited’s sudden demise last week left few market players unscathed. Shareholders, in particular, got soaked in the bloodbath that preceded the company’s rescue by the South African Reserve Bank on Sunday.

The regulators moved swiftly to maintain confidence in the local financial system, but there are several questions about the lifeline the central bank threw to African Bank. Why did it have to be bailed out? And why did the regulators not act sooner to defuse the ticking time bomb that the bank had become?

Reserve Bank governor Gill Marcus announced that the bank will be put under the curatorship of Tom Winterboer of PwC. It will be split in two: a “good” bank with a loan book value of R26-billion, which will be recapitalised by R10-billion, underwritten by a consortium of private sector banks and the Public Investment Corporation (PIC); and a “bad” bank, with a book value of R17-billion, which the Reserve Bank will take over and buy for R7-billion.

Retail depositors, a mere 1% of the bank’s creditors, will be fully covered in the transfer to the good bank. But other creditors, chiefly the bondholders, will lose 10% of the value of their investment. Shareholders and subordinated debt holders will get nothing but the opportunity to participate in the new bank.

African Bank’s ill-fated retail furnisher business, Ellerines, a R70-million-a-month drain on the holding company and African Bank, has been placed in business rescue.

Bad business model

The bank’s business model was a contributing factor to its financial woes, according to Byron Lotter, the portfolio manager of Vestact. Unlike other banks, it took almost no deposits but raised funds on local and international capital markets, which it then lent to consumers as unsecured credit at high interest rates.

In response to increased competition in the unsecured market, African Bank aggressively expanded their lending, but when tough economic conditions hit lower end consumers non-performing loans soared Lotter said.

Restoring faith in the broader financial system was a key issue, Wayne McCurrie of Momentum Wealth said. The bank’s debt is widely held in the financial system by other banks, pension funds and money market unit trusts, he said.

Had the bank not been bailed out, it could have compromised the value of the bank’s good book, affecting its ability to raise funds in the future, he said. Besides local debt, it has issued bonds internationally, the most recent being in February when it issued 175-million Swiss francs (slightly more than R2-billion) on the SIX Swiss exchange.

It is also not clear how the debt write-downs will take place, Peter Attard Montalto, an analyst at Nomura, said in a research note, especially for foreign investors holding the bank’s Swiss franc and United States dollar denominated debt. It will be part of the good bank but interest payments have been frozen for the foreseeable future, he noted. It appears the 10% write-down will be on the principal but it may also be on the interest payments, he said.

Rating downgrade

On Wednesday, ratings agency Moody’s downgraded the bank’s credit rating to Caa2 and placed it on review for a further downgrade.

Another source of funding was money market instruments, which also face a 10% cut.

Jurgen Boyd, the deputy executive officer of the Financial Services Board (FSB), said 15 money market funds, out of a total of 43, held African Bank paper. With total assets valued at R270-billion, 1.3% were exposed to the bank. The FSB has instructed them to write down 10% of this exposure immediately, in effect pricing in the impact of its decline, Boyd said.

Fitch Ratings downgraded Absa’s money market fund on Wednesday. Fitch also placed another five funds including money market funds from Investec and Nedgroup Investments, as well as Stablib’s Extra Income Fund, on a negative ratings watch, because of their exposure to the bank. Of the local money market funds rated, Absa has the highest, longest-term exposure to African Bank, it said.

But shareholders were the biggest losers. The share price plunged more than 90% in two days. The largest included the PIC, whose equity exposure was 15%, and it held 6% of bank-issued bonds. Others included a number of high-profile asset managers, such as Coronation and Liberty Life’s Stanlib.

Stanlib held 8% of the issued shares on behalf of its clients and had exposure to equity, bonds and debt, it said, but these were very small in relation to the total funds under management of R560-billion.

Unanswered questions

Serious questions still remain about how things got so bad, despite the bank management’s reassurances in recent months. Following a R5.5-billion rights issue last year to recapitalise the loss-making bank, its management was adamant it could return to profitability. This changed after its shock trading update last week, revealing that it faced R7.6-billion in losses and needed a further R8.5-billion from the market, sparking its share price plunge.

Montalto asked why the regulators did not do more, and sooner. The Reserve Bank indicated that it had engaged the bank over its loan book, and the NCR should have acted in 2011 and 2012, when reckless lending at the bank was building up, he said.

The Reserve Bank should also have rejected the bank’s purchase of Ellerines, which was “solely to further cement Abil’s [African Bank’s] undiversified business structure in providing more clients for unsecured credit”, he said.

The NCR said it had investigated the bank, noting the R20-million settlement it reached with the bank early this year. High levels of bad debt and credit impairment are not only caused by reckless behaviour but also by economic factors, which affect consumers’ ability to repay debt, it said.

The Reserve Bank and the treasury did not respond to requests for comment.

A previous version of this story suggested Stanlib’s money market fund had been placed on a negative ratings watch, when it was in fact Stanlib’s Extra Income Fund, which was placed on negative ratings watch. We regret the error.