NEWS ANALYSIS

The return of Lesotho Prime Minister Thomas Thabane to his home country under South African police escort on Wednesday might not be the end of the political instability in that country.

Indications are that the fragile coalition of three parties – none of which has a majority of seats in Parliament – might not be able to hold out for much longer.

Confusion also reigns over whether deposed army chief Lieutenant General Tlali Kamoli is willing to step down. Kamoli, who was sacked from his post last week, is seen as being at least partly responsible for last weekend’s violence in Lesotho that left one police officer dead.

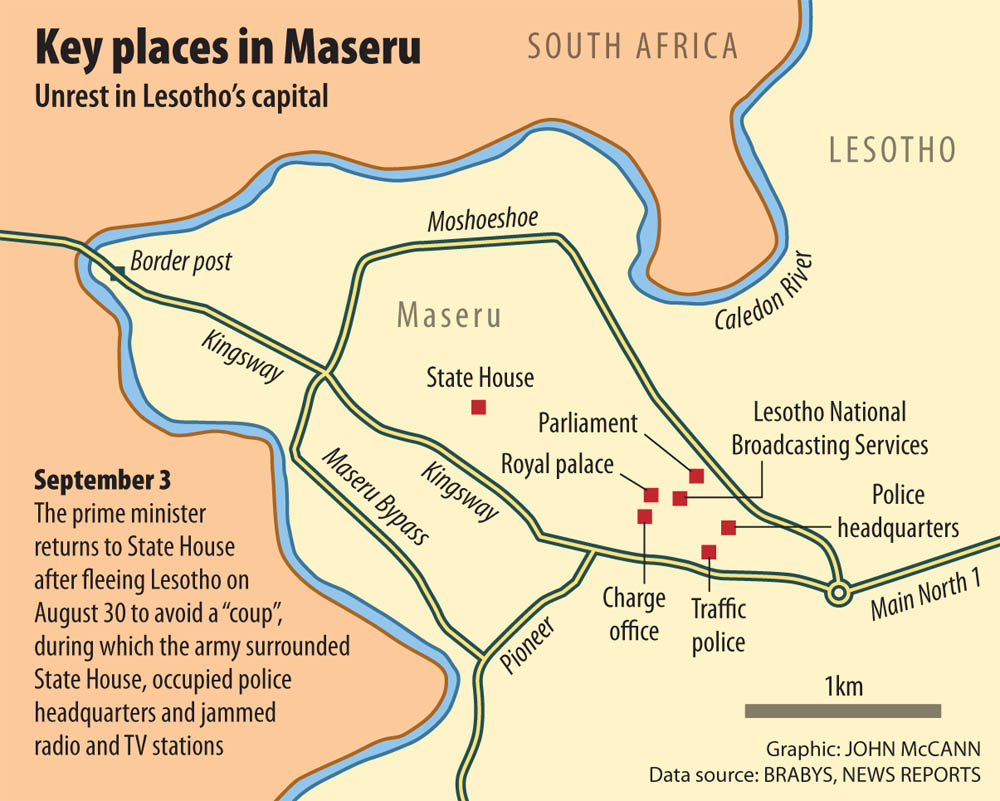

The army stormed police barracks to seize weapons and then apparently moved on to capture Thabane himself. Thabane fled to South Africa over the weekend, alleging that a coup d’état was being carried out.

The military, however, insists that it was merely acting on intelligence that the police were planning to disrupt a march on September 1 by Thabane’s rival, Deputy Prime Minister Mothetjoa Metsing. Metsing and his Lesotho Congress for Democracy party are unhappy about Thabane’s suspension of Parliament in June this year and had planned on marching to insist that the executive be reconvened.

Army spokesperson Major Ntlele Ntoi told the BBC on Tuesday that Kamoli was still in charge.

Vote of no confidence

Sources in Lesotho say the possibility of a vote of no confidence against Thabane in Parliament cannot be excluded in the coming weeks.

According to an agreement reached between the two parties on Monday, mediated by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), a “road map” with timelines on how to lift the suspension of Parliament has been established and will be presented to King Letsie III.

SADC had tried several times in the past few weeks to solve the crisis, but the rivalry between Thabane and his deputy, Metsing, seems beyond repair.

Sources say, even if Parliament is reconvened speedily, it could still take several days to prepare the agenda for the year. A vote of no confidence by some of the parties against Thabane could, however, be treated as a matter of urgency.

On Sunday President Jacob Zuma, as the chair of the SADC organ for politics, defence and security, convened the three coalition leaders, who undertook to work together.

They also agreed to implement the Windhoek agreement signed on July 30 that Namibian President Hifikipunye Pohambe, then chair of the SADC organ, had tried to mediate. This weekend’s crisis showed that Namibia’s mediation had little impact on the situation on the ground.

On Thabane’s side

If violence breaks out again, South Africa is expected to side with Thabane, but only up to a point. Thabane had asked for military intervention by South African troops on Sunday, but the SADC agreement makes no mention of such aid from the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) or from the regional body.

Instead, a task team is being sent to help Lesotho to sort out its problems.

Independent defence analyst Helmoed Heitman said this week that it is unlikely that the SANDF will “willy-nilly” get involved in the unrest in Lesotho, but if it gets worse South Africa might have no choice.

“If comes to a shooting match, then South Africa will certainly get involved,” he said.

The SANDF has the capacity to undertake a short-term mission of a few months in Lesotho, but is also tied up with missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in ensuring security along the country’s borders.

Nations in the region would all be able to assist in such a mission, but Heitman says it is unlikely that countries such as Angola – and its large army – would be willing to serve under a South African command.

At the time of the last SANDF intervention in Lesotho in 1998, Botswana was the only SADC country willing to assist South Africa but arrived on the scene too late, “when it was all over”, said Heitman.