Loan businesses are suffering following the Marikana strike.

Disturbing cases of rising bad debt and indications that African Bank misrepresented aspects of its business in its financial reports have called into question whether the lender can be revived, and raises concerns that the state could be on the hook for more money than it expected.

The National Credit Regulator (NCR) found the bank had contravened the National Credit Act in charging more than R600-million in fees that it should not have, promoting speculation that an investigation into the bank’s business could uncover more transgressions and hamper the bank’s ability to collect on debts.

If the Reserve Bank-appointed investigation of African Bank finds evidence of reckless lending, the loans could be set aside, giving the borrower a debt holiday.

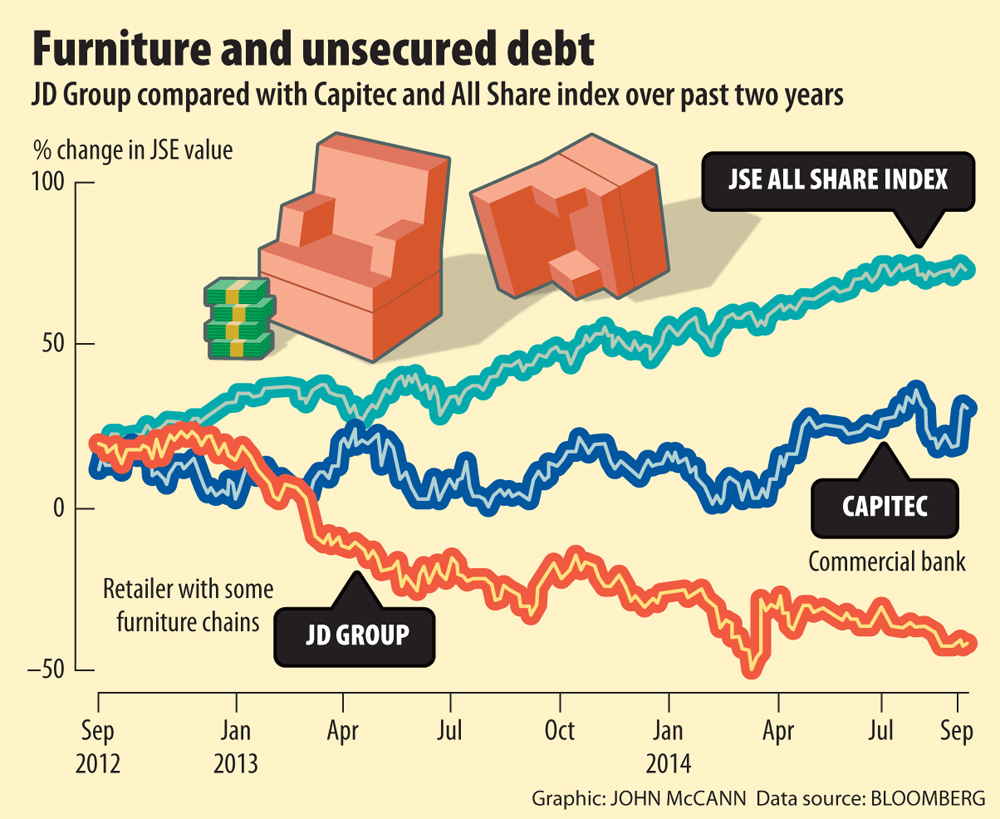

Many furniture retailers are reliant on credit sales, such as the JD Group, which this week released results that show a company in distress as bad debts rise at an alarming rate, resulting in provision for a sixfold increase. The group posted a loss of almost R2-billion on turnover of R3.6-billion. Bad debts climbed to R841-million in the financial year ended June 2014 from R505-million in 2013.

The Lewis Group last reported that debtor costs had increased by 30%. Bad debts as a percentage of total had risen from 9% to 11%. Lewis reported operating profits of R1.15-billion on turnover of R5.2-billion.

‘Instant cash’

In Marikana, where police killed 34 protesting miners in August 2012, over-indebtedness was rife. Cash loan shops lined the main street and were filled with prospective clients waiting in queues to apply for an “instant cash” loan.

When the Mail & Guardian visited Marikana this week, there are now just four. A large number of them near Anglo Platinum have also closed.

The five-month long strike on the platinum belt took its toll on lenders, and they say they now have to contend with tighter regulations and more onerous collection procedures. The manager of one cash loan shop said the business didn’t have enough money to lend.

“Getting a garnishee order used to take a month; now it takes two months. There is no money in the business.”

But bucking the downward trending in the unsecured lending sector, the country’s second-largest unsecured lender, Capitec, said this week it expects a 22% rise in earnings in the first half of the year, noting in a trading statement that its bad debts results were in line with its risk appetite, which factored in market conditions.

Government funding

The Reserve Bank, having split African Bank in two, has committed itself to buy the book of the “bad” part of the collapsed lender (which is worth R17-billion) for R7-billion, and has agreed to underwrite part of the R10-billion that will be used to capitalise the “good” bank.

But depending on how it plays out, the state might have to fork out much more.

Jean Pierre Verster, an analyst at 36One Asset Management, said the mixed messages coming out of the unsecured lending industry made it hard to estimate the value of African Bank’s good bank book, which the Reserve Bank believes is worth R26-billion in net portfolio investments.

“It doesn’t make me feel strong in my conviction in the estimated book value and there is definitely a risk the Reserve Bank could be on the hook for more than expected,” Verster said.

Following a boom in 2012, the drop-off in unsecured credit was sudden and distinct in mid-2013.

Reckless lending

The slow-down in the economy contributed to it but tighter regulation also played a leading role as reports of reckless lending, the abuse of emolument attachment orders (garnishee orders) and credit life insurance began to receive widespread publicity, especially following the Marikana massacre.

In November 2012, the treasury announced it would begin to crack down on reckless financiers, causing lenders to pull back on unsecured credit.

Dragged down partly by the loss-making Ellerine Furnishers, African Bank was the first victim of the changing credit cycle and tightened regulations.

In 2012, the furnisher had written off R1-billion in bad debts out of its R6.4-billion credit exposure. In December 2013, the Reserve Bank told African Bank to sell Ellerine, which was losing at least R70-million a month.

On August 10 this year, after African Bank’s share price collapsed, the Reserve Bank stepped in, placing it under curatorship.

Bad bank book

The book for the bad bank comprises a substantial part of its non- and under-performing assets. George Glynos, the managing director and an economist at ETM Analytics, said it was understood that the asset purchase, although facilitated by the Reserve Bank, was funded by the treasury.

“They are buying the bad book at a massive discount. At this point, one is uncertain whether the losses that will be sustained will be as large as the discount that they have secured. If the losses are less than the discount secured, they could make back some of this money.”

But it depends on how well the bank is able to collect on these debts.

Meanwhile, the Reserve Bank last week appointed John Myburgh, an advocate, to “investigate the business, trade, dealings, affairs, assets and liabilities of African Bank”.

Verster said “the appointment of a commission implies there could be a problem”.

Questionable business practices

Indications of questionable business practices have already emerged in Parliament, when Minister of Trade and Industry Rob Davies responded to questions, and said the NCR was aware that African Bank has transgressed a provision of the National Credit Act in charging more than R600-million in excessive charges and, in effect, contravened the in duplum rule, the Burger reported.

The rule, section 103 (5) of the National Credit Act, states that the amounts that accrue during the time that a consumer is in default may not exceed the unpaid balance of the principal debt under that credit agreement.

But in its integrated report for the year ended September 30 2013, the bank stated: “Abil [African Bank Investments Limited] has applied this requirement consistently across all its portfolios, when defaulting loans reach the in duplum threshold (threshold loans) and thus no interest, fees or charges have been raised on customer accounts on these threshold loans.”

That was a red flag, said Verster. “They misrepresented the situation in the annual report. Whether it was a wilful or negligent misrepresentation, it’s just one example that we know of that the commission could find.

“There could be more … and they could find that there is a fire where we clearly know there is smoke.”

New business generation

Verster said the bank’s unsecured lending book remained relatively short-term in nature even though the terms were extended as part of the rescue, and that the bank needed to generate new business to cover relatively fixed expenses.

“They need to manage the appearance they are open for business so people come in and take out new loans, and pay for existing loans.”

Nomsa Motshegare, the chief executive of the NCR, said that, should the investigation find alleged reckless loans, these matter would have to be referred to the courts. In terms of the National Credit Act, only the courts could decide whether loans were reckless or not.

If the court determined that the credit agreements were reckless, it might make an order setting aside the rights and obligations of the consumer, all or in part, under these agreements or suspend the force and effect of these credit agreements.

“The consequences of suspension of a credit agreement is that the consumer is not required to make any payment stipulated under the agreement; the consumer may not be charged any interest, fee or other charge under the agreement; and the credit provider’s rights in respect of the agreement cannot be enforced,” Motshegare said.

Should the Reserve Bank require additional funding in this case, the treasury could raise fresh capital on the bond market or tap into contingency reserves, Glynos said.

The treasury and the Reserve Bank did not respond to questions sent to them by the M&G.