Sasheer Zamata has been hired on 'Saturday Night Live'.

In the latest crime figures for the Sophiatown police station, up to February, murder was up by 42%, attempted murder was up by 25%, aggravated robbery was up by 33% and hijackings doubled. A dilapidated block of flats in Sophiatown houses hundreds of police members and their families. This story looks beyond the walls at their living conditions.

A couch, stained and ripped, sits abandoned in a parking lot populated by broken-down vehicles with cracked windows and flat tyres. Empty beer bottles and discarded items litter the overgrown grass.

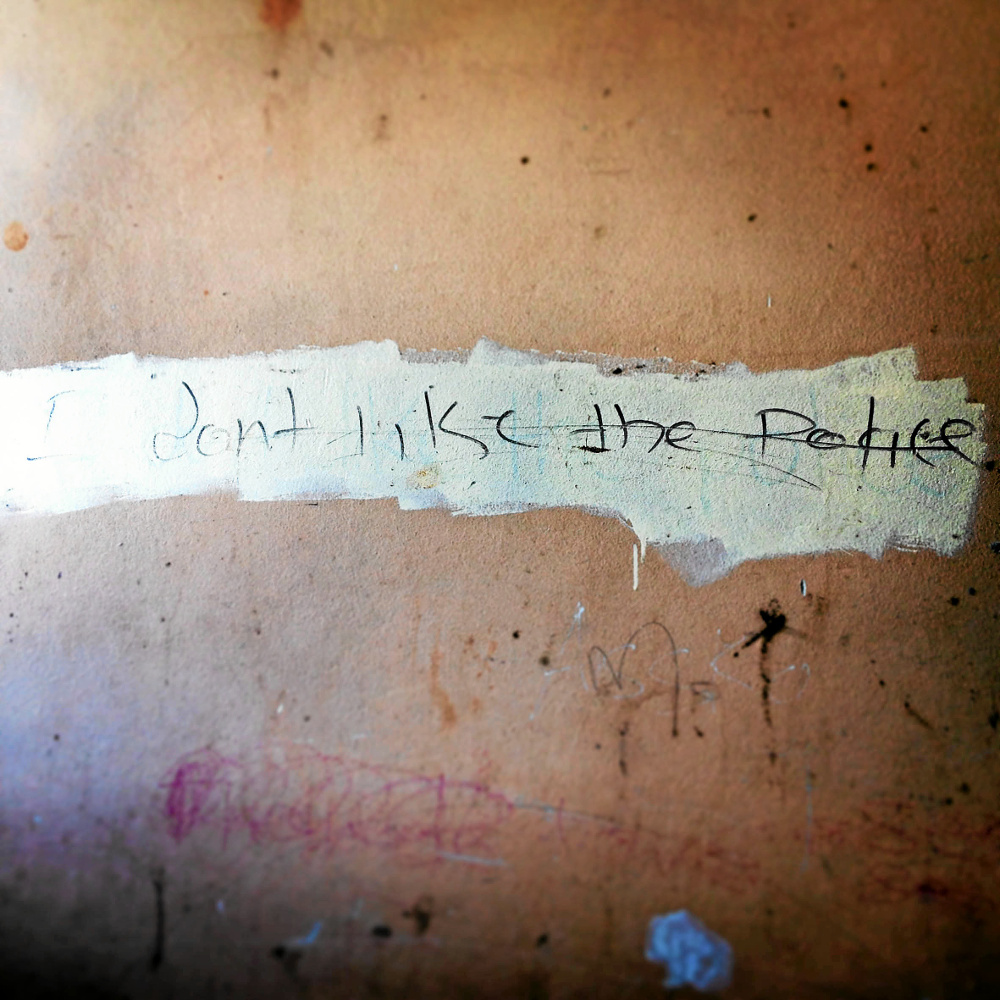

The voices of young children singing Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star are carried on the wind and the smell of stale urine hangs heavy in the air. “I don’t like the police” is scrawled defiantly on a face brick wall in black permanent marker.

Despite its dilapidated appearance, this is not a condemned building in Hillbrow and it is not a residential block in Cape Town’s notorious Cape Flats gangland. This is the Herdeshof building in Johannesburg’s historical Sophiatown, which is better known as “police flats” or “cop flats”.

In South Africa, there are more than 30 buildings like Herdeshof – designated police barracks and police compounds in which SAPS members (and in some cases their spouses and children) are housed.

The building might be mistaken for a beacon of safety and security by virtue of the large number of police who live there. But this assumption is quickly disproved. Petty crime – such as cars being stolen from the parking lot and flats being broken into – occurs often, at times allegedly even perpetrated by children of the police officers who live there, but mostly attributed to criminals from “outside”.

Station hierarchy

This distinction between the flats and the “outside” (the surrounding suburbs) – and by extension the distinction between police and non-police – would presumably create a deep-rooted sense of community within the tall block of flats, but the police are quick to identify themselves with the police station they serve, almost as if there is a hierarchy among the stations that sets them apart from their fellow residents.

Nevertheless, the competing melodies blasting from countless radios through kitchen windows, children tirelessly kicking a soccer ball in the lane next to the garages, people trying to fix broken cars and women exchanging conversation while hanging up laundry on communal washing lines – together, they evoke a sense of community.

The towering 15-storey building created a Big Brother-like effect in Sophiatown during apartheid, with residents feeling as if they were constantly being watched by the all-seeing police. But 20 years into democracy, the building has the appearance of a tarnished structure that has not been upgraded or repaired in decades.

Herdeshof is home to 184 police officers and their families. (Photos: Kyla Herrmannsen)

In June 2012, the Sunday Times exposed the slum-like nature of some of these buildings. The report, “Barracks are worse than jail cells: Inside the slums where our men and women in blue must live”, detailed the grave disrepair of many of these police housing units.

The Natalia Court Barracks in Durban have reportedly been without functional lifts since 2006 and, closer to home, the Alexandra Barracks have been without hot water for almost 15 years.

The report revealed that many of the more than 30 buildings had officially been labelled “unsafe for occupation” – a health and safety threat to their occupants – prompting the then newly appointed national police commissioner, Rhiya Phiyega, to declare that, under her tenure, the repair of police living quarters would be a priority.

Legal responsibility

But it was also noted that the department of public works, which owns the majority of the buildings and leases them to the SAPS, is legally responsible for maintaining them.

The Sunday Times report was met with outrage; the Democratic Alliance issued a statement condemning the slum-like nature of the quarters and called for immediate action to be taken to repair the buildings.

The building’s filthy foyer only hints at the state of neglect at the Sophiatown police quarters.

“In the case of the SAPS barracks, for example, creating better living conditions for our policemen and women is essential to improving the morale of our police service. This is essential if we are to effectively fight crime and make South Africans feel safer,” said Anchen Dreyer, the party’s public works spokesperson at the time.

In the dishevelled parking lot of police flats in Sophiatown, it is all too evident that the promises have remained empty. Although it might not make the top of the “horror list” of slum-like state-owned police dwellings, the building is clearly in a serious state of disrepair – you have to dodge litter and broken glass when walking outside and the buttons of the lifts, which have been broken for years, have been ripped out, removing any doubt that they might be working.

Dominating the skyline, it is the largest and tallest building in old Sophiatown and has housed SAPS members stationed in and around Gauteng since the 1970s.

‘Married quarters’

Of the hundreds of police who call cop flats their home, 184 are stationed at the nearby Sophiatown police station. The building is zoned as “married quarters”, which means that the police are allowed to live with their spouses and children in the flats. Each flat is made up of three basic rooms.

“To sustain your family, your family needs to be near you as the breadwinner,” says Siya Mahola*. “A half a loaf is better than nothing … as long as you can survive daily,” he added, referring to the meagre earnings of the police. “It is better than getting nothing at all.”

He is stationed at the Sophiatown police station and is a resident at police flats.

According to him, “if you’re single, you can’t stay here because you’ll become a bully. We want couples, not singles.”

The assumption underlying this is that single police force members are likely to drink more alcohol and be rowdy “troublemakers”. There is a sense of greater security, and perhaps even community, when only families inhabit a building.

Rent deduction

A nominal fee of slightly less than R500 a month is deducted from their salaries for rent. This includes water and electricity. Entry-level SAPS employees earn less than R10 000 a month, so such a low rent is attractive.

Gareth Newham, the head of the governance, crime and justice division of the Institute for Security Studies, says police are paid “more than teachers, nurses and other public servants at the same grade in the public service”.

But, paying them slightly more than their teaching and nursing peers does not necessarily translate into the police feeling valued either by society or the SAPS.

‘I don’t like the police’ is scrawled defiantly on a face brick wall in black permanent marker.

Newham says: “There is a prevailing sense among many officers that the public do not appreciate the work they do. Similarly, due to poor management across the SAPS, many officers do not think that their supervisors and, therefore, the organisation generally, adequately value the work they do.”

But, despite the disrepair of the state accommodation, many police count themselves lucky to be among the few who get to live at police flats.

“Staying here is not your right, it’s a privilege,” says Mahola emphatically.

Flats in the block are so sought after that there is a waiting list. “It’s a long process,” he says. “You apply, then they put you on the waiting list.”

Side business

Despite saving on rent by living in relative squalor, some members of the SAPS still struggle financially. Jan Pretorius* is using the building to its full advantage and recently turned his garage into a fringe business – a tuck shop. His wife and her friend, Beauty, who is also the wife of a police officer, are running the business for him.

“No pizza, no burgers, just kasi food,” says Beauty, explaining the menu with a broad smile.

The kasi (or township) food she refers to is ikota, sandwiches of bread, chips and sausage, which inspired the name of the business, Papa D’s Kotas.

But the legality of running a “side business” is governed by mounds of paperwork and strict rules issued by the SAPS.

Newham says: “Police officials have to get written permission before undertaking any additional work for remuneration.

“Certain kinds of work, such as working for private security companies or owning taxis, is prohibited.

“However, again, because of the low risk of police officials being held accountable for breaking the rules, many police officials do engage in additional private work without obtaining prior permission.”

Regardless of its status, Papa D’s Kotas brings a sense of community to police flats, with the children returning home from school eager to buy a packet of chips, carefully dodging the multitudes kicking around a ragged soccer ball and singing along to the latest one-hit-wonder pop tune blasting from a nearby portable radio.

Unfair dismissal

Linda Ndlovu*, a former SAPS employee, was one of the lucky few to have been allocated a flat on the sixth floor several years ago. She still lives there with her husband and eight children. The youngsters run around the flat in circles, never tiring and never stopping for long enough to have the snot running from their noses wiped away.

A quiet, sombre figure busies himself in the midst of this screaming toddler-filled flat, dusting the curtains and washing the dishes, paying great attention to every speck of dirt. This is Ndlovu’s eldest son; he is 21 and was born with Down’s syndrome. “He loves to clean,” says Ndlovu, smiling in his direction.

Broken furniture litters the Herdsehof parking lot.

She used to be a policewoman stationed at the nearby Sophiatown police station. She claims she was unfairly dismissed in 2009, following a leave of absence. She says she was hospitalised for severe depression and that, although she informed the SAPS of this and requested extended sick leave, the SAPS claimed she had stopped coming to work and fired her.

Ndlovu, who is trying to win her job back, remained in the flats, which technically means she and her family are squatting there because she is not paying the mandatory nominal R500 a month rent. Despite this, she is vocal about the dilapidated state of the building.

“My geyser has been broken for a long time and nobody has come to fix it,” she complains. She says it is leaking and has created damp, resulting in her children becoming chronically ill – hence the relentless snotty noses.

“When I have money, I will try to fix it little by little,” she says. “Before, they had cleaners who would come regularly to clean the building and, if something was broken, they would send someone to fix it,” she says, reminiscing about the good old days when she first moved in to the building.

Visibly upset, Ndlovu says that the deterioration in maintenance boils down to racism.

Her logic: there used to be many white police officers and their families living in the flats; now “there are just two to three white people so I think they don’t care anymore, by the looks of things”.

Although the building is leased from the department of public works, the SAPS is responsible for the day-to-day maintenance of the building, such as picking up litter. Public works is responsible for the larger tasks, like repairing cracked windows and fixing the lifts.

But, despite public works punting itself as the “handyman of the state” on its website, the block of flats is in complete disrepair.

Petty crime

Petty crime is also an issue. An A4 notice, created simply in Microsoft Word and stuck to walls, states: “The criminals are back breaking into garages and cars parked on the parking area. We should start with the night patrols before everyone becomes a victim of crime in a police flat.”

Ndlovu endorses this and says that, although Sophiatown is known to be an unsafe neighbourhood, petty crime has breached the gates of the flats.

“Even in the police flats it’s not safe. Lots of cars and flats get broken into … These guys, they come from Westbury and they rob us,” she says.

The Herdeshof building is better known as ‘police flats’ or ‘cop flats’.

But she believes the children of the residents themselves are also to blame. Recently, her son’s new bicycle was stolen and, she says, pawned by the son of a police officer living in the building.

“If you are a police officer staying in a police building and it’s not safe … imagine, just imagine, the people who are living elsewhere,” Ndlovu says, expressing her disappointment with the SAPS.

Unfulfilled promise

To salvage and upgrade the police flats in Sophiatown, the SAPS would need to make good on a promise from 2012 that they would make repairing police barracks and police compounds a priority.

In doing so, police would have to admit responsibility: instead of simply laying the matter at the door of the department of public works, the SAPS would have to apply pressure on the department to perform its so-called “handyman of the state” duties. And the department would have to stop throwing the matter back to the police.

But the back and forth of this blame game has frozen any possibility of development while the police officers and their families continue to live in a sub-standard building that, if neglected any further, could become a serious health and safety risk.

In the meantime, Ndlovu sits on her threadbare couch in her gloomy flat – all the curtains are closed, her children, in the midst of a frenzied game, are running from wall, the mould and water damage from the broken geyser is noticeable on the lounge walls – reflecting on her years in the block of flats and, to a greater extent, as a former SAPS employee.

“I don’t feel valued,” she laments.

This is part of a series by the Wits Justice Project, which investigated the Sophiatown police station in Johannesburg. It serves a diverse area, in a sense a microcosm of South Africa, which includes some of the country’s poorest people and a comfortable middle class. For more information, go to sophiatowncritical.co.za.

* Names have been changed.