It's easy to blame Amcu

NEWS ANALYSIS

In the confusion immediately after the Marikana massacre, there was enough blame to go around. The police had done the shooting. The mineworkers had done the threatening. Mining company Lonmin had been blind to the danger. The government had failed to intervene. There was horribly visceral evidence of structural problems in the mining sector and in the police – problems that had to be addressed urgently.

But politicians and business leaders were intently focused on what they described as an immediate threat to everything from peace and stability to economic growth – the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu).

Even as forensic investigations at Marikana continued, companies beyond the platinum sector (and some beyond mining) started investigating Amcu “contagion” in their operations.

Political analysts presented business clients with confidential research reports warning about the implications of Amcu’s rise: unceasing and possibly violent labour unrest, a decline in production, a weakened currency. Leaders of political parties considered a future in which Amcu became the centre of a leftist storm.

This week, after two years of sometimes excruciatingly detailed investigation, evidence leaders at the Farlam Commission of Inquiry presented a very different picture of Amcu.

Bumbling organisation

The union they describe was neither an engine for chaotic protest nor a skilful manipulator of workers, but rather a bumbling and opportunistic organisation caught up in the same chaos as everyone else.

“One of the key criticisms directed against Amcu was that it was behind the [rock-drill operators’] demand and the strike, and that it promised its members an increase to R12 500,” the evidence leaders wrote in their submission to the commission.

“However, the evidence before the commission is that the [rock-drill operators] did not want to involve the unions in raising their demands.”

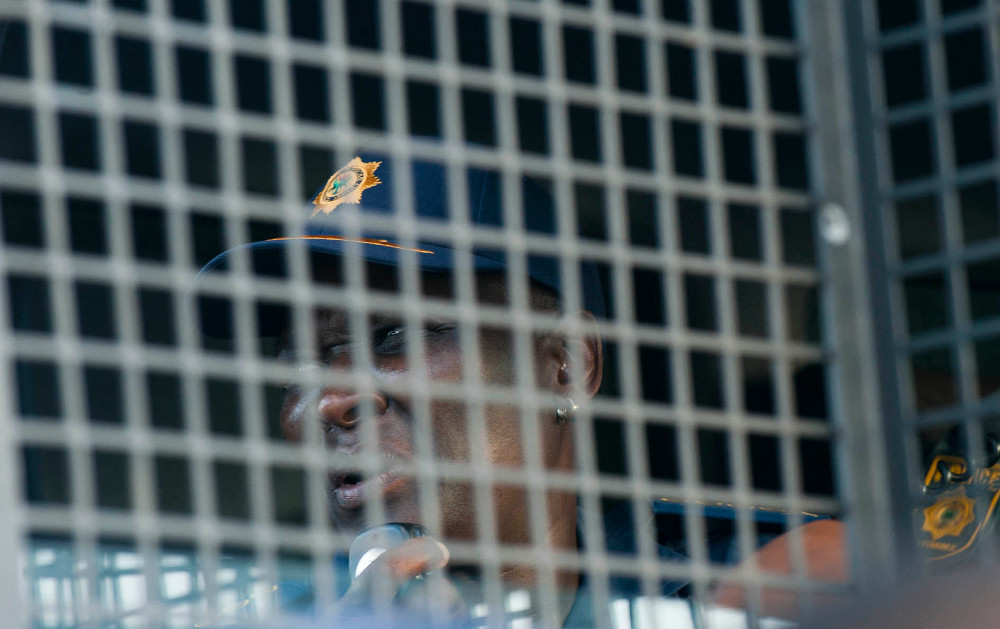

Amcu’s Joseph Mathunjwa was unable to persuade striking miners to come down from the Marikana koppie. (Photos: Delwyn Verasamy, M&G)

In fact, they said, the allegations from rival union the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and Lonmin notwithstanding, “there is no concrete evidence before this commission which points to Amcu being behind the strike and the violence which ensued”.

For those negotiating with Amcu, there is perhaps a warning in the evidence leaders’ assertion that Amcu lied to the commission. Then again, so did just about everyone else: government leaders gave the public information that “was materially misleading”, and workers injured or arrested “disputed the indisputable” and “gave an improbable account of their own role”. And the police, in the words of the South African Human Rights Commission, engaged in “half-truth, obfuscation, nondiscovery and omission”.

Honest and trustworthy

Measured only by the summary of the evidence before the commission, employers should consider Amcu a far more honest, trustworthy party in negotiations than the South African Police Service.

Crucially, the commission’s evidence leaders believe that Amcu head Joseph Mathunjwa tried to exploit a situation not of his making to strengthen the position of his union – but failed.

“We submit that Mr Mathunjwa was not candid with the commission in his initial testimony and that he was seeking to turn the situation to the advantage of Amcu by demanding to be recognised as a bargaining partner in the wake of the strike,” they wrote in their submission to the commission. “Ultimately, however, this demand was rendered redundant because he was unable to get the workers off the koppie.”

Mathunjwa’s ambition was matched by his optimism that he could sway workers to leave that gathering place, but he failed. And an emerging consensus from the mining industry may point to why he failed.

Immediately before the Marikana massacre, and for at least several months after, Lonmin, police, captains of industry and leaders in politics clung to a simplistic explanation for events there: Amcu had incited workers who would otherwise have been happy with their pay and conditions; it had fanned the flames of violence and then unleashed havoc.

As is the case in at least some township service-delivery protests, it turns out that looking for agitators as the cause of unrest entirely misses the point.

Convenient as it is to blame ringleaders, insurrection is caused not by leaders but by poverty, inequality and the anger those factors engender. Even the mining industry seems ready to admit as much.

“What we witnessed was a major social uprising and a revolt,” Anglo American Platinum chairperson Valli Moosa told a mining conference in October. – Additional reporting by Sarah Evans

Restructure and demilitarise the police now, urge lawyers

Recommendations by evidence leaders to the Farlam Commission of Inquiry this week are more than mere criticisms of the police – they advocate nothing short of a total overhaul of the police, from top to bottom.

The commission is hearing closing oral arguments by the legal teams after two years of painstaking investigation into the causes of the shootings on August 16 2012, when 34 people died and more than 70 were injured.

The evidence leaders, led by advocate Geoff Budlender SC, this week implored the commission to recommend sweeping changes to the police in their report to President Jacob Zuma.

This is not to say that retired Judge Ian Farlam has to take on board their recommendations – but the opinions of senior legal counsel such as Budlender and his team are convincing on their own.

The recommendations begin with national police commissioner Riah Phiyega, whom the evidence leaders found to be “less than candid” in giving evidence. The recommendations stop short of accusing Phiyega of perjury – for this, the president should establish an inquiry into her conduct at the commission.

“The SAPS [South African Police Service] response to this commission of inquiry has been characterised by concerted attempts to mislead the commission on several central issues, including the role played in relation to the events of August 16 2012 by the national commissioner herself and the other generals,” the evidence leaders say.

“The national commissioner herself must have been aware of this, yet did nothing to stop it.

“Her immediate response to the shootings was incompatible with the office of the head of a police service in a constitutional state.”

They go on to say: “Her refusal in evidence to repudiate her statement on August 17 2012 that ‘whatever happened represents the best of responsible policing’ suggests that she is not fit to hold the office of national commissioner. So, too, does her dogged refusal to criticise any aspect of the conduct of SAPS in relation to the tragedy of August 16.”

Riah Phiyega ‘is not fit to hold the office of national police commissioner’, the Farlam inquiry has heard.

The evidence leaders’ recommendations go further: the police must be demilitarised as a matter of urgency, and policies that dictate the use of force in crowd policing scenarios must urgently be reviewed. The use of R5 rifles – such as were used by the police on August 16 2012 – must stop “immediately”.

Plus, all police must be trained in first aid, the evidence leaders say. One miner was left to bleed to death for about an hour just after the shootings “while the police stood idly by” waiting for ambulances to arrive.

The “organisational culture” of the police needs overhauling, they say, and the “serial crises” of police management must be addressed. The evidence leaders also found that one of the reasons the police intervened on August 16 2012 was to end the strike – an “inappropriate” move on their part that was allegedly motivated by political considerations.

“That was an entirely impermissible and illegitimate purpose. The SAPS should not be used to break strikes, whether protected or unprotected,” the evidence leaders told the commission this week.

But perhaps the most stinging criticism of the police – besides recommendations that the shooters should be held responsible for the miners’ deaths – concerns their conduct at the commission.

The implications of the evidence leaders’ allegation that the police actively tried to cover up and conceal evidence, and then lied under oath about it, are the anti-thesis of what is expected of any nation’s police force.

The evidence leaders believe that the police hid crucial video evidence showing what happened at the site where most miners died. The footage was only discovered when the evidence leaders went looking for the SAPS’s master hard drive.

Furthermore, a meeting the police held after the shootings to prepare their evidence at the commission led to a further cover-up, they say. The evidence leaders want the police members concerned to be charged for this. – Sarah Evans