Global financial reforms are coming thick and fast and South Africa will not be immune — significant changes are being made to regulation, including imminent rules to ensure that failed banks will be bailed in and not out.

The treasury says these measures will be similar to the capital instruments known as contingent convertibles, or CoCos, which have been implemented in Europe to stabilise the financial sector and have created a new asset class, which is growing in popularity among banks and investors despite their risky nature.

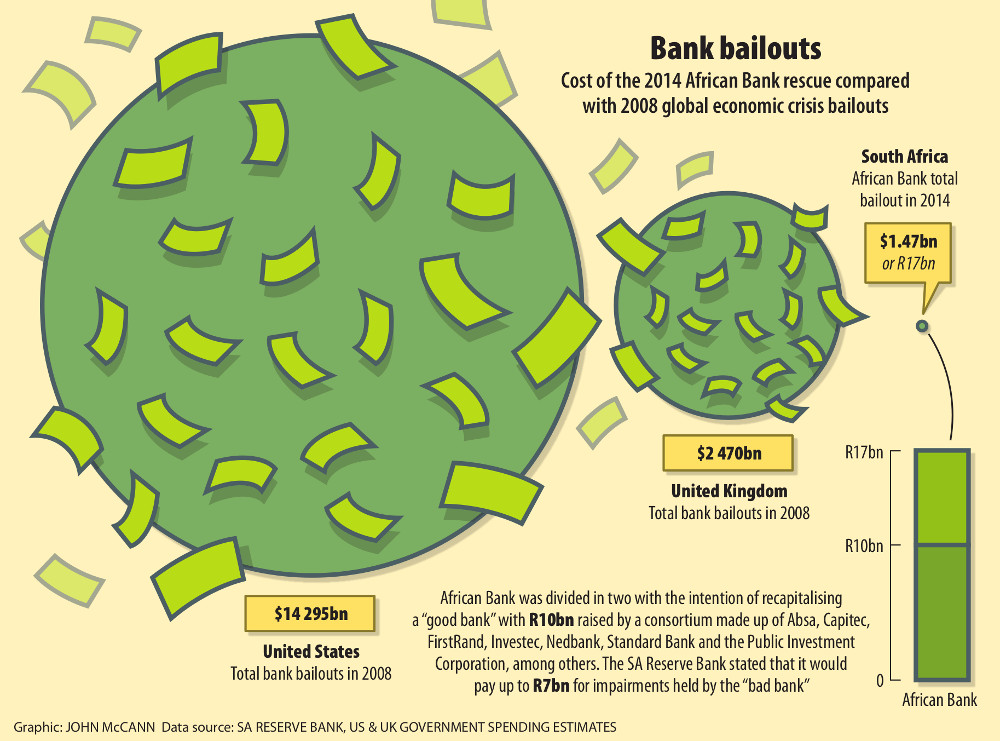

There are many reforms for financial institutions to address issues that range from market conduct to financial crime, but the emphasis remains on eliminating the threat to the “too big to fail” banks, which are so systematically important that governments cannot allow them to fail — the likes of which were bailed out by central banks during the 2008 financial crisis.

The resilience of South African banks in the face of the economic downturn was applauded but, in August, African Bank had to be rescued by the Reserve Bank, which will pay up to R7-billion to recapitalise the bank’s nonperforming loan book.

But governments are feeling the heat of having to bail out failing banks and are introducing instruments to ensure it is the shareholders who bail out a bank and not the taxpayer. This is known as a bail-in.

“We have a whole work programme for bail-in instruments and we will be bringing a Bill probably during in the course of next year,” Roy Havemann, the treasury’s chief director of financial stability and banking, said. “We have always been very proud of our well-regulated banking system but we need to keep up with international best practice.”

Basel III

Significant progress has already been made on higher capital and liquidity requirements, drawn up by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, known as Basel III, which is being phased in worldwide. Thirty “global systemically important banks” have been identified by the G20’s Financial Stability Board (FSB) and are now required to hold “total loss-absorbing capacity”, additional capital to avoid the potential loss of the bank. It will need to be between 16% and 20% of their assets.

These banks include HSBC, Credit Suisse, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank and Barclays.

Havemann said there were several loss-absorbing capital instruments, of which CoCos were just one type.

“As far as bail-in instruments go, South African banks are already kind of on track. Some have even come close to issuing these,” he said. “Total loss-absorbing capital is a relatively new concept but bail-in instruments have been around for a few years.”

The Reserve Bank has not elected to use CoCos yet but, as a Barclay’s Africa spokesperson said: “There are instruments similar in nature to these CoCos, which will be issued, and these instruments should be utilised in distressed situations and provide additional protection to depositors.”

CoCos have two main design characteristics: a trigger level and a loss-absorption mechanism, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Essentially, they are converted from debt to equity in times of stress and are triggered when the capital of the bank that issued them drops below a certain level (to satisfy Basel standards, the trigger needs to be 5.125%), acting as a buffer by rapidly reducing debt and boosting capital.

“The CoCo market is still relatively small, but it is growing,” the BIS said in a 2013 quarterly review, noting that banks had issued $70-billion worth of CoCos between 2009 and September 2013 compared with $550-billion of nonsubordinated debt and $4.1-trillion of senior unsecured debt.

In September, HSBC issued $5.6-billion in CoCos of these bonds.

Tax efficiency

According to Henderson Global Investors, issuing debt such as CoCos is also tax-efficient and has become a popular choice for banks trying to fill additional capital requirements. These types of bonds were first issued in 2009 but have grown in popularity over the past year, and investor demand has climbed, despite their risky nature, because of their higher yields in a low interest rate environment.

BIS said: “The yield to maturity of newly issued CoCos is on average 2.8% higher than that of non-CoCo subordinated debt and 4.7% higher than that of senior unsecured debt of the same issuer.”

But regulators have raised concerns about selling this kind of bond to ordinary investors who may not understand the risks.

Being a bail-in instrument, if the CoCos are converted to equity, this “doesn’t pay interest and is first to be wiped out if a bank fails”, according to the Wall Street Journal.

South Africa’s banks are able to meet most of the basic Basel III requirements, although the net stable funding ratio has proved to be a sticking point (See “Meagre deposits a sticking point for banks”). But the need to reform regulations to allow bail-ins is imperative.

A bail-in was used to some degree in the rescue of African Bank, in which the measures included the recapitalisation of the bank by the Reserve Bank and, to some extent, by bondholders and wholesale depositors, who took a 10% haircut (the difference between the market value and the purchase price of an asset).

Anthony Smith, the head of KPMG’s financial services regulatory centre of excellence, said the African Bank crisis was “exacerbated by the way the bank was structured with a reliance on short-term wholesale funding and only offering unsecured loans. Had we had things like a total loss-absorbing capacity, or CoCos, the bank may have been able to withstand the crisis.”

Early adopter

The Reserve Bank has generally been an early adopter of legislation that it views as being necessary to improve or maintain the sovereign rating of and create confidence in the South African banking sector, he said.

Havemann said there was always a risk of overregulation, and one had to be careful and aware of the implications.

“The FSB has a process through its emerging markets and developing economies subgroup. It issued a report which analysed the implications of the reforms particularly on emerging markets.”

Finn Elliot, an associate director of KPMG’s corporate law advisory practice, said there would always be downsides to regulation but one had to understand that the regulators were trying to close the gaps exposed by the recent financial crisis. “They do need to change and enhance the regulatory framework but it is going to place a significant cost burden on business,” he said.

Smith agreed: “One of the consequences [of reforms like Basel] is that holding more capital is expensive. So we have seen global banks exiting businesses, such as fixed income, currencies and commodities, because it’s capital-intensive.”

Smith said reform was necessary but the costs of complying were significant.

“The consumers are going to see the burden of the increased regulation; it’s got to flow through.”

Meagre deposits a sticking point for banks

The Basel III reforms, prompted by the financial crisis and supported by the G20, seek to shore up the ability of banks to withstand systemic shocks with more stringent capital and liquidity requirements, phased in from January 1 2013 to January 1 2019.

South Africa’s banks have been able to meet the Basel requirements for capital from the outset, as a result of conservative capital rules domestically, but meeting the liquidity requirements was always going to be an issue.

The liquidity coverage ratio, which requires banks to have liquid assets of cash or assets easily converted to cash to meet cash outflows during 30 days of stress, posed a challenge at first. But the Reserve Bank remedied this by setting up a R240-billion facility available to banks — which satisfy the requirement — when in need.

Another liquidity requirement, known as the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR), is a significant component of Basel III but has become a sticking point for domestic banks with inadequate retail deposits.

As the Bank for International Settlements explains it, the NSFR “requires banks to maintain a stable funding profile in relation to their on- and off-balance sheet activities, thus reducing the likelihood that disruptions to a bank’s regular sources of funding will erode its liquidity position in a way that could increase the risk of its failure and potentially lead to broader systemic stress”.

Stable funding includes customer deposits. But South Africans are regularly lambasted for not saving and the national savings rate (which discounts pensions and life industry products) remains low. Banks are partly to blame for offering low interest rates that fail to attract deposits.

“Attracting the savings is a challenge, and one way to meet the requirement is that the banks will need to pay higher interest rates on retail deposits,” said Roy Havemann, the national treasury’s chief director of financial stability and banking. He noted that many banks had raised interest rates and were bringing out new products to attract deposits.

“Some are paying up. I think it’s a consequence of the regulatory reform and it makes them stable in the long run.”

Havemann said the government had a role to play. Last month the treasury published the draft notice and regulations required to allow the introduction of tax-free savings accounts (with a contribution cap of R30?000 a year) to encourage individuals to save.

The NSFR will become a minimum standard by January 1 2018 and the treasury has processes in place to test whether the banks’ strategies will enable them to meet the requirement.