A freefall in commodity prices has come to a head at the end of 2014 as crude oil, iron ore and coal prices, among others, took a significant tumble and served to bring one global giant – Russia, the world’s ninth-largest economy – to its knees.

The problem facing most resources is that high levels of production have seen supply outstrip global demand, resulting in low commodity prices. Resource giants with low production costs will weather the storm until supply tapers and prices pick up again. High cost producers will probably fall over.

The commodity fall can largely be attributed to slowed demand from China which is switching from an investment-focused economy to a consumer-oriented one.

Iron ore, a key component of steel, has been particularly hard hit, dropping from $136 a tonne to $73. South African export coal prices have fallen from $84 a tonne to $65. Platinum has dropped from $1 400 an ounce to near $1 200. Copper kicked the year off at $7 400 a tonne, but ended it at $6 300.

“For most of the metals markets, 2014 has been a year of adjusting to the rebalancing in the Chinese economy. Demand growth is still positive, but it is simply slowing,” said Grant Sporre, a commodities strategist at Deutsche Bank.

Currency despair

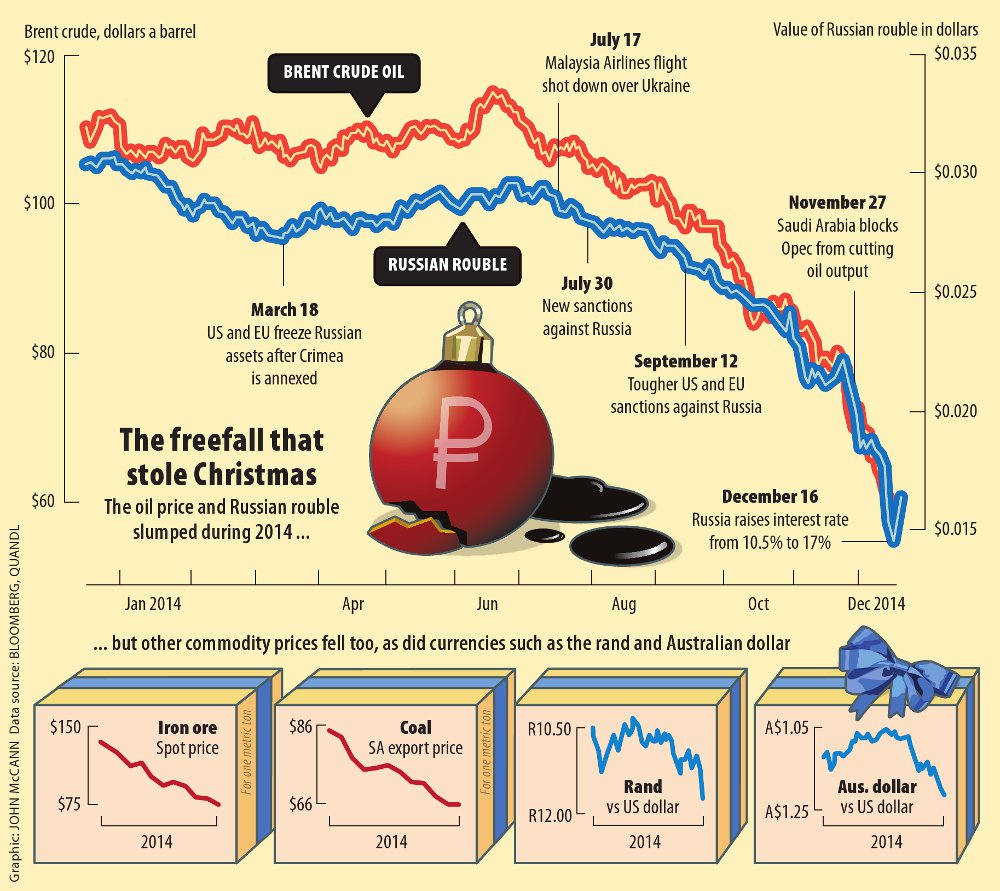

The most dramatic price move this year was that of crude oil and had little to do with the slowdown in China when it crashed from more than $110 a barrel in July to below $59 in recent days, causing a crisis in the Russian economy. Russia’s oil production cost is $105, according to the Guardian.

Oil producers in the Middle East, seeking to secure market share in light of a natural gas boom in the United States, have taken a decision not to cut supply for now, prompting estimates that the price could slide further to $40.

Consumers have rejoiced in the news but substantially negative impacts became clearer this week in Russia when the central bank, following an emergency meeting at 1am on Tuesday (in response to a plummeting rouble which lost 49% of its value this year), announced it would hike its key interest rate from 10.5% to 17%.

The move did not stop the currency from falling further on the day, as much as 19% according to Bloomberg, before an announcement that Russia would sell its foreign currency reserves saw the rouble recover. Still, media have reported that Russian banks are running out of foreign currency as people bring in piles of cash to swop. According to the Wall Street Journal: “Sberbank, Russia’s state savings bank, and Alfa Bank, Russia’s largest private lender, said they were experiencing a rush for dollars and euros.”

The economy has suffered under sanctions from the US and Europe in light of its invasion of Ukraine earlier in the year, with more to be signed by US President Barack Obama by the end of the week, and has now been severely affected by the cost of crude as its government is heavily reliant on oil revenues.

The crisis in Russia has prompted concerns about contagions seeing the market sell off other emerging markets’ currencies, bonds and stocks. The MSCI emerging market index, which includes South Africa, dropped since the news of Russia’s dramatic interest rate hike. These jitters, too, prompted the Turkish lira to hit record lows against the dollar on Tuesday.

Although not an oil producer, South Africa has historically been a resource-reliant country and, although it has diversified since, minerals and metals still account for 60% of its export revenues. South Africa’s trade deficit, reflecting billions more in imports than exports, is already a worry for the government and ratings agencies which have expressed concern over the widening gap last reported in November as R21-billion – its highest level in four years.

Like Russia, but not to the same degree, other commodity-producing countries like South Africa, Brazil and Australia have seen domestic currencies weaken against a strong US dollar.

The rand, at 11.70 to the dollar on Wednesday, was at its lowest level in six years.

But these weak currencies have, in fact, served to cushion commodity producers in the face of declining prices.

“Most producers are getting a bit of help from local currencies as a significant proportion of their costs are in local currencies but they generate revenue in US dollars,” said Sporre. “So they can live with a lower commodity price longer than you might anticipate. With the rand weakening, for example, a lot of platinum group metal producers that were lossmaking at the beginning of September are now breaking even. The rand has bailed them out.”

Although the weak currencies enable resource companies to hang on for longer, action from the supply side is inevitable and the lower commodity prices ultimately act as a disincentive for investment.

In 2012, the mining sector paid R5.6-billion in royalties to the government for the extraction of the minerals and R21.4-billion in direct corporate tax, which accounted for 14.1% of total corporate taxes paid in South Africa.

Time for action

Andries Myburgh, a tax partner at ENSafrica, said the lower commodity prices would undoubtedly have an impact on tax revenues and mineral royalties, and affect more than just mining companies. A poor commodities price outlook could also require capital expenditure to be put on hold and possibly prompt retrenchments in a bid to reduce costs. “That would not necessarily impact immediately on mining companies but for service providers, such as construction companies, that would impact their revenues,” said Myburgh. Retrenchments would naturally also mean less personal income tax on which the receiver could collect.

“Mining companies have been under pressure for quite a while because of low commodity prices and high costs, and Sars [South African Revenue Service] is under pressure to collect,” he said, adding that the lower prices would see mining companies deciding to cut production and that may affect exports and the balance of payments

Sporre said different metals faced different supply-side concerns. Even though nickel and platinum group metals have experienced supply shocks this year, the price has dropped as there is a lot of metal in global inventories that will require a period of constrained production in order to deplete.

Those markets which have been driven to supply cuts, have been under pressure for some time. These are the aluminium, coking coal, and zinc markets. Production cuts, particularly in zinc and aluminium, have seen prices stabilise and even start to appreciate.

In industries such as iron ore and copper there is an issue of supply momentum where, after years of investment, projects are coming online and bring new supply into the market, pushing down the price. “In iron ore you need a lot of the higher cost producer to close for market to reach any kind of balance,” Sporre said.

The same is true for crude oil where the suppressed price will probably force high-cost producers out of the market.

“I think we still need to see producers take more proactive steps to limit supply,” said Sporre. But he noted that large miners, such as Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton, have projects that tend to be at the low end of the cost curve “so they are still going to make good margins and have every incentive to carry on producing”.

Indeed, BHP Billiton has continued to ramp up production despite a falling iron ore price, although it has recently announced it would reduce the costs in bringing on new production as it can lower its investment without slowing volume growth.

Glencore continues to invest in copper despite the current market oversupply. “But their time horizons are a lot longer, and there is likely to be a deficit market towards the end of the decade,” Sporre said.

Although bullish on copper, the resources giant has, however, faced supply and demand facts for coal and, in November, announced it would stop its thermal coal production for three weeks in an attempt to lift prices from a five-year low.

Speaking at Glencore’s investor day on December 10, chief executive Ivan Glasenberg said capital misallocation (particularly in iron ore which Glencore does not mine) and not lack of demand was the biggest problem for the mining sector at present.

“We will continue our disciplined approach to capital allocation, based on the supply/demand fundamentals, as well as maintaining our focus on operational efficiency,” Glasenberg said.

Plummeting JSE

The JSE All Share index may have reached all-time highs of 52 000 in July this year, but of late the market is closing at lower and lower levels, often dragged down by resources on the day.

“Over five years the resource index has lost 20% of its value. It tracked sideways for four years until January this year, edged higher and then came down sharply in sympathy with declines in oil, metal and mineral prices,” said Kavita Patel, business unit head portfolio manager at Sasfin Securities.

“As China moves into a more consumer-oriented economy, obviously South Africa will take a big hit being a resources-driven economy.” Still, the JSE doesn’t fully reflect the fall we are witnessing at the moment, Patel said.

“South Africa used to be largely resources, but also if you look at the top 15 companies which account for 70% of JSE’s market capitalisation, the portion of that being resources has been shrinking over the last few years.” The market caps of platinum and gold mines in particular have been shrinking while giants such as Naspers, SAB Miller and British American Tobacco have buoyed the exchange.

“At the moment there is excess supply in the market and South Africa is hit from two sides,” said Patel. “There is move away from emerging markets and, as China slows down, it puts pressure on commodities markets as there is excess supply and not enough demand.

“Then there are domestic issues, for local commodities companies facing increasing cost pressures, in addition to labour and electricity supply concerns.”

Over the past five years, AngloGold is down 69%, Anglo Platinum is 59% lower while iron ore miner Kumba is down 47% in 2014.