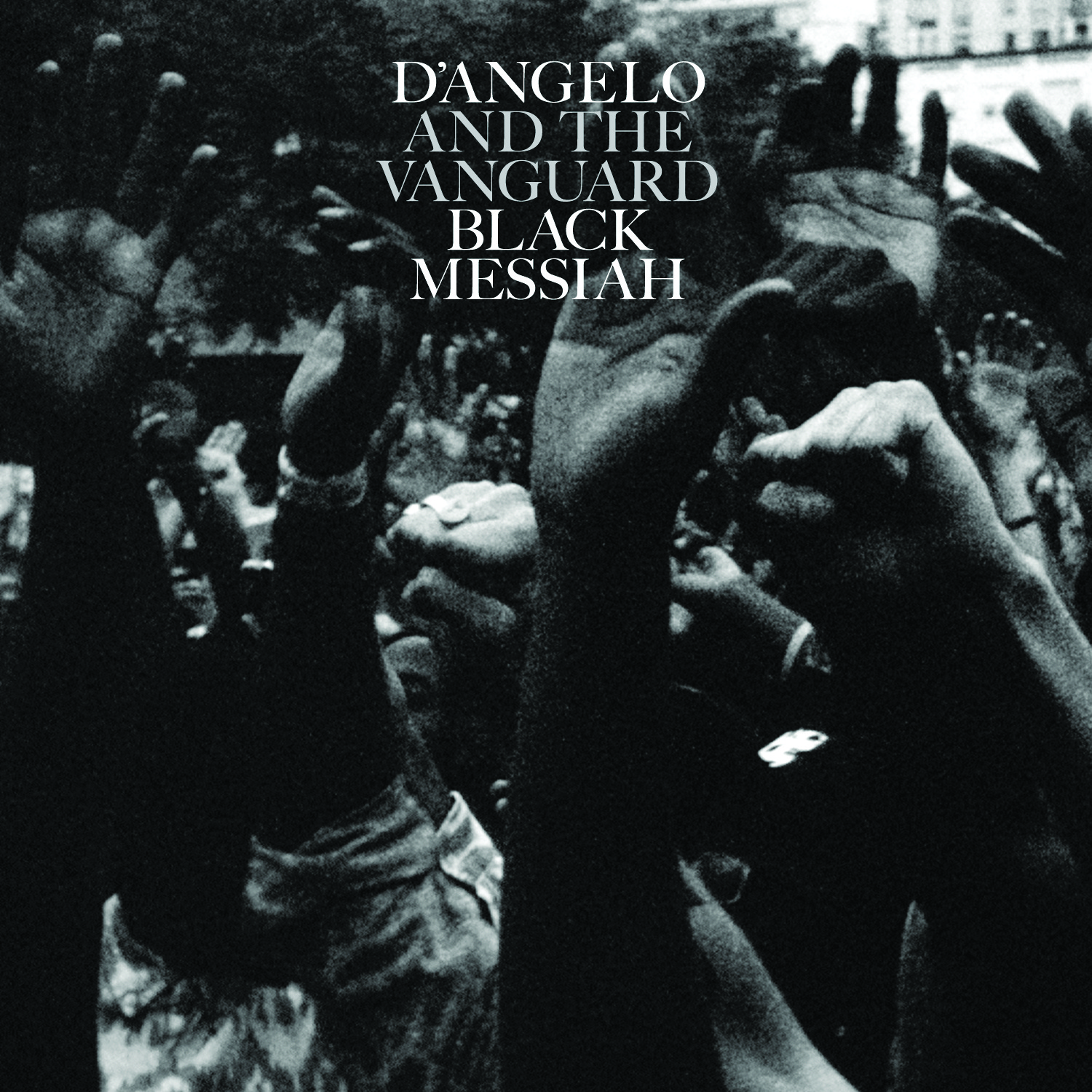

‘Some will jump to the conclusion that I’m calling myself a Black Messiah. For me, the title is about all of us,” read a pamphlet handed out at Michael D’Angelo Archer’s listening session in New York recently.

“It’s about people rising up in Ferguson and in Egypt and in Occupy Wall Street and in every place where a community has had enough and decides to make change happen. It’s not about celebrating one charismatic leader but celebrating thousands of them … Black Messiah is not one man. It’s a feeling that, collectively, we are that leader.”

It was a select group of the music industry’s anointed who sat with the cultural critic Nelson George and Questlove from The Roots and listened – or, as Okayplayer suggested, “worshipped” – to D’Angelo and the Vanguard’s long-awaited third studio album Black Messiah.

It was this kind of veneration – and one too many panties thrown on stage – that in the 14 years preceding this release nearly drove D’Angelo to playing out the “tormented genius, premature death” role, which has always stalked him. And he got close.

Two serious car accidents within a few months – one of which propelled him head first out of the passenger seat, through the windscreen – left him in intensive care, with a crash hangover and battered body, and no less determined to wreck his life while still hoping to make great music.

Stream Black Messiah here:

Breaking the internet

It was his friend and prolific producer J Dilla’s cruel death after a battle with lupus at the age of 32 that raised the stakes for the self-taught prodigy from Richmond, Virginia. “I felt like I was going to be next. I ain’t bullshitting. I was scared then,” he told GQ in June 2012.

But we have him back and are we ever grateful. Superlatives and melodrama exploded all over the internet last week, from Justin Timberlake and John Mayer to Idris Elba, Erykah Badu and Common. The glee was magnetic and infectious. If anything was going to break the internet, this was it.

By the time South Africans woke up to the news that the album was available for download, it was already number one on iTunes. It was a digital hijack from an old analogue soul who technically isn’t even on Twitter.

The last time a body of new work was available from him we had just survived the Y2K damp squib and Napster was still alive. It was a different time for the world and the music industry. A thread on Buzzfeed reminds us that in the year 2000 (when Voodoo, D’Angelo’s second album, was released) J Lo and Puff Daddy were an item; the Sony PlayStation 2 went on sale; Survivor debuted in the United States; you were using a Nokia 3310; and Amadou Diallo had reached into his pocket for a wallet for the last time only a year before, when police shot him in New York.

The saviour of soul

In the (almost) 15 years since Voodoo, D has been in rehab, relapsed and tried again. He has tried to purge his sex symbol persona, put on weight, lost it again, and is now somewhere in between. He has fought with bandmates, ostracised friends and battled with keeping himself out of jail.

During that time in the US, Trayvon Martin was shot and iconised the hoodie; Eric Garner had the life choked out of him; and an unarmed Michael Brown was shot many times – by a “five-year-old”, we are urged to believe. Black America is raging and, as the lists of the year’s best records are hastily amended, it has found an album to believe in.

As early as February 2002, D’Angelo’s kindred creative collaborator, Raphael Saadiq, said he had set aside the latter part of that year to help to produce D’Angelo’s next offering. It never came to pass and the time since then is littered with odd cameos, gossip and not much music – at least none that we heard. And this from someone with a platinum album that received two Grammies.

He was once called the saviour of soul and the rock critic Robert Christgau dubbed him the R&B Jesus. Although he might shy away from the hype, it would seem the second coming is here. For such a long time it seemed as though he needed to be saved, and now he has returned with a simple message: we are the saviours we have been waiting for.

Religion, spirit, struggle and lust

To have him, after 14 years, touring successfully in Europe, the US and Australasia, and having shared new music – in a world without Whitney Houston, Amy Winehouse and Michael Jackson – shows he has saved himself, at least for now. Religion, spirit, struggle and lust live happily in Black Messiah, as they did in Voodoo.

It is raw, dirty, sweaty and at times depraved. It is a very secular kind of gospel – the kind the devil flirts with and an atheist takes on a second date. D’Angelo has worked with bassist Pino Palladino, superstar Questlove, Q-Tip and a new collaborator, singer-songwriter Kendra Foster.

The familiar mix of love, sex and sociopolitics comes at you in various ways. It pleads desperately to an estranged lover in The Door, it postures in Sugah Daddy over a groove reminiscent of Chicken Grease and Betray My Heart is a bluesy reprise of Spanish Joint. He channels Prince’s psychedelics in the mood-capturing The Charade: All we wanted was a chance to talk/ ’stead we only got outlined for chalk.

1?000 Deaths is jarring, mangled guitar screeching over inaudible, ominous lyrics: I can’t believe/ I can’t get over my fear/ they are gonna send me over the hill …/ I was born to kill/ send me over the hill.

The crux

The US police are facing the worst crisis of trust between them and minority groups, and black men are continually being vilified in spite of evidence of their continued persecution.

The symbol of all that was possible for black Americans, Bill Cosby, is dodging 17 claims of sexual abuse. Barack Obama, the man whom Americans twice voted to lead them, faces what was always an inevitable time in his presidency: the day when he had to deal publicly with the fact that the US has deferred the “black problem” for far too long. Sadly, he seems ill-equipped, unwilling or hamstrung by politics as usual.

The voices speaking out – ministers, senators, basketball players and comedians – are as many as they are varied in their cogency. Those voices needed Black Messiah. They needed an album that would capture the mood, set it up and toss it back to the people, imbued with a renewed energy and more probing questions.

To declare that D’Angelo, and more pointedly, the release of Black Messiah, will liberate the US from its inertia in the face of the crumbling facade of the land of the free would be to overstate the matter. The album will do nothing to dissuade trigger-happy, militarised law enforcers – with a low tolerance for blacks who speak up for themselves – to change.

D’Angelo’s resurrection resonates far more poignantly in the music world than on the streets of Newark or Philly. But his fans (famous and otherwise) are many, and their ears and beings are open not only to new music from an idol but also to a sense of verity in art – an eternal lightning rod for inclusiveness.

Nobody does it better

Usher cannot do it, Trey Songz cannot hack it, Chris Brown is preoccupied, Miguel is a false prophet, Maxwell seems meek, Bilal’s charisma is limited, Musiq was better as a soul child, Moses Sumney is fleeting and Rahsaan Patterson lacks grit. There are many others on different levels of the R&B/neosoul stratum, but none can inhabit it as easily as D’Angelo can. It is his calling and he has the talent – and no pretender, even during his extended hiatus, has come close to that crown.

There are some who have been too hasty in dismissing Black Messiah as somewhat inferior to Voodoo, but they have short memories. They forget that, despite D’s purity and extraordinary homage to Sam Cooke, Marvin Gaye, Al Green and other greats, Brown Sugar was perhaps too clinical, too perfect, rather like the perfect recital with your piano teacher (coproducer and engineer Bob Power in this case) looking over your shoulder, with a long ruler at the ready to strike your fingers if that E was too sharp.

Voodoo was a bolt out of Pentecostal tongue-speaking, chicken-sacrificing, night-vigiling, foot-stomping ecstasy, where love, lust and the gospel lived comfortably. But in many fans’ hearts its raw edge was a slow burner.

Black Messiah might be just that for many others, but the breakthrough will happen. In the meantime, D’Angelo’s message of the need for social and environmental justice and an end to war –Till It’s Done (Tutu) – will resonate loud and clear.All the rage: D’Angelo plays into black America’s demands for social justice.