The success of foreign-owned spaza stores comes down to competitive pricing.

Dear Ms Lindiwe Zulu,

Many South Africans, including you, have observed the success of foreign-run spaza shops in the townships and think the reasons for their success are a mystery.

But this sector is well studied, and research has revealed many so-called trade secrets, which include hard work and business acumen.

You have called for tougher regulation of foreign businesses in the townships to be fast-tracked, but you have also said that some aspects of the small business regulations are too restrictive.

From your first hours in office as the minister of small business development, you said that South Africans needed to learn from foreigners running successful small businesses. What has been done about that is unclear.

Now that the looting and violence, fuelled by xenophobia, has continued in Soweto and surrounding areas in recent days, your tone has become more demanding. You said (as reported in the press) that foreign business owners in the townships cannot expect to coexist peacefully with local businesses unless they shared their acumen.

Extensive research by several organisations on how foreign-owned spaza shops are run provides a great deal of insight, although I’ll admit the picture is not always complete and, at times, contradictory.

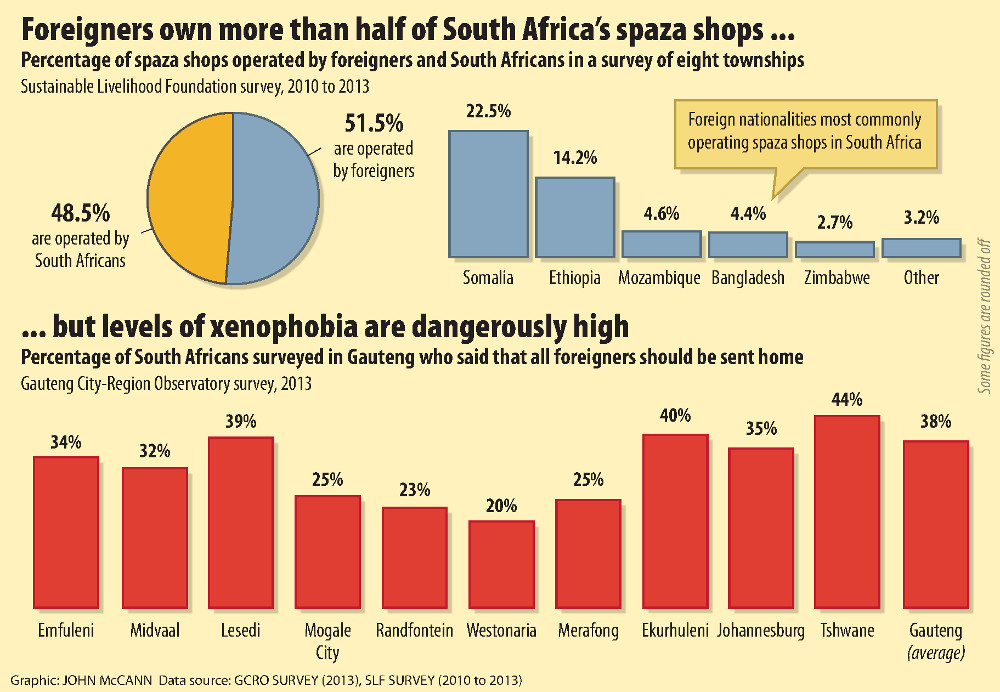

The nonprofit organisation Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation is one of them. In its Formalising Informal Micro-Enterprise (FIME) project, it interviewed 950 spaza-shop businesses in eight townships between 2010 and 2013.

The research affirmed that foreign-run shops dominated the market. More than 51.5% of spaza shops in the survey were run by foreigners, and these were often linked to partnerships.

Typically, they were owned by Somalis, Ethiopians and Bangladeshis, although it did note that several South Africans were equally competitive.

One key advantage of these larger partnerships is that, by clubbing together, they had more start-up capital (between R20 000 and R60 000), enabling them to stock their shops well. Each store spent, on average, R7 000 a week on stock.

These larger shops attracted more customers because of longer trading hours (from 6.30am until 10pm) and, most importantly, lower prices.

Through their business networks, the spaza-shop owners were able to buy goods in bulk and get price discounts, and transport costs were shared. They established delivery agreements with suppliers and had access to high-demand products, the FIME research found.

On the other hand, Vanya Gastrow, a freelance researcher and PhD candidate at the African Centre for Migration and Society, said her research found that spaza-shop owners did not buy in bulk.

Instead, individuals shopped around for the lowest prices and specials to be competitive. But shop owners did share transport to reach a wider range of wholesalers, she said.

Tashmia Ismail, the head of the inclusive markets programme at the Gordon Institute of Business Science, has done extensive work on spaza shops in Johannesburg’s Diepsloot. She agreed that the success of foreign-owned stores came down to competitive pricing, and some items were even sold at cost to lure foot traffic into the store.

Ismail said business savvy was just in some people’s genes. “If you look at the literature on migrant groups, they seem to have a DNA of business. If you leave home, you have to make it. The stakes are high, you can’t afford to fail.”

Research has yielded different findings on whether foreign spaza-shop owners hire locals, but Gastrow said South Africans were the biggest economic beneficiaries of the sector, because the vast majority of foreign spaza-shop owners rented premises from them.

Gastrow said: “There are lots of claims that foreign nationals have sophisticated trading methods which South Africans can’t adopt but, actually, many of the methods they use to be competitive are not highly complex … But there is a definite lack of engagement between foreign nationals and South Africans.”

Among locals, including you, Ms Zulu, there is a perception that foreign shop owners do not always play by the rules. And, indeed, better access to contraband tobacco, for example, has emerged as a key advantage for foreign-owned shops.

The FIME research found that 37% of the spaza shops surveyed sold contraband tobacco, and the majority of those were foreign owned.

The procurement of supplies requires a network of co-operation and substantial capital. Contraband tobacco is sold mostly in bulk, with orders of R50 000 to R100 000 at a time. But, in a bid to compete, some local shop owners sell liquor, which Muslim traders won’t stock. Of the shops surveyed in the FIME project, 82 locally owned, and only 11 foreign-owned, shops sold liquor.

There is also a concern that some foreigners don’t register their businesses and apply for permits to trade.

The requirements for informal traders differ between municipalities. No permits are required for spaza shops in Cape Town, but they are required in Johannesburg.

Many informal businesses do not register because, critics claim, of the difficulties involved, including the cost and red tape.

“You’re looking at a minimum of R300 to register an entity and then more to reserve your name. It will cost R750 to R1 000, even without permits or factoring in time,” Anton Ressel, a senior business consultant at the enterprise development consultancy Fetola, said.

“There is no incentive to register. It is almost a disincentive to be on the radar.”

Toby Chance, the Democratic Alliance’s spokesperson on small business development, said that, in Johannesburg, informal businesses were not necessarily being registered.

“It’s almost certain that many of the police are on the take,” he said.

But the city’s spokesperson, Virgil James, insisted that regulation was being enforced. He said those running spaza shops had to register their businesses where city planning required it.

“When it [an illegally operating business] comes to our attention, it is closed down. The laws are in force; there are inspectors sent out who check for contravention,” James said. “The policy and bylaws are indiscriminate; it doesn’t matter if you are local or a foreign national.”

But, he added, the city was consulting stakeholders to improve the regulation of informal trade.

Meanwhile, the contentious Licensing of Businesses Bill sits in Parliament, which requires that all businesses must be registered with their municipalities, which will have the power to impose restrictions and conditions.

Detractors argue that additional restrictions, which are aimed at illicit trade, could, in fact, kill legitimate businesses, both foreign and local.

Yours sincerely,

Lisa Steyn

A previous version of this article stated that permits are not required for informal trading in Cape Town. In fact, informal trading permits are required for informal trading from demarcated trading bays in public spaces like pavements and markets. However, permits are not required for spaza shops because they do not trade from public spaces but from private properties.