Crushed: A man weeps as he joins parents of kidnapped schoolgirls during a meeting with the Borno state governor.

Using a new approach to DNA analysis, the 17th century bones of three African slaves have been traced to their countries of origin for the first time, researchers said this week.

The three slaves analysed in their study came from what is modern-day Cameroon, Ghana and Nigeria, according to the findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a peer-reviewed US journal.

The approach, called whole genome capture, circumvented the problem of scarce DNA and was able to almost narrow down to the subject’s villages, with one coming from a Bantu speaking area of Cameroon, and the other two from non-Bantu-speaking areas of Nigeria and Ghana.

The new approach would help solve a key problem: until now, uncovering the precise origins of the 12-million African slaves sent to the New World between 1500 and 1850 has been challenging, since few historical records exist from the time. Often, the ports from which the slaves were shipped is known, but not the nations from which they came.

In February, the US and Canada marked Black History Month, dedicated to remembering important people and events in the African diaspora. While it always sparks a colourful debate over relegating the history of one race to a single month, there has been less controversy over the need to track the historical origins of Africans transported during the slave trade.

One such leading project is the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, an ongoing collaborative effort sponsored by Emory University, the US agency the National Endowment for the Humanities, and Harvard-based W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, and roping in scores of other partners.

The comprehensive database describes itself as “the culmination of several decades of independent and collaborative research by scholars drawing upon data in libraries and archives around the Atlantic world” and is available on open access on the Voyages website.

It also runs the African Origins project, a collaborative project between scholars and the public, which seeks to use audio recordings of names in the African Names Database to trace the geographic origins of Africans transported during the transatlantic slave trade.

Researcher David Eltis for Emory wrote an introductory overview of the trade that brims with fascinating facts, an essay that we excerpt to better understand the phenomenon:

1: What was unique about the trans-Atlantic slave trade?

- It was the largest long-distance coerced movement of people in history, and prior to the mid-19th century, formed the major demographic well-spring for the re-peopling of the Americas following the collapse of the Amerindian population. The Americas (North, Central and South America) were the destination for the vast majority of enslaved Africans transported overseas, and who were mostly put to work in the plantations and mines of the European-run colonies.

2: Why did the Amerindian population collapse, and who were they?

- The Spanish and Portuguese, on the back of exploratory work of names such as Christopher Columbus, were among the earliest explorers into the New World, or what is known as the Americas. In their zealous colonising effort they destroyed many of the pre-Columbian inhabitants. Between 1492 and 1550 the Amerindian population of the West Indies had been reduced by 90% due to massacres, importation of diseases such as smallpox, and destruction of local agriculture by the incomers. The colonists then sought shipments of enslaves Africans to replace the locals and work in the New World plantations and colonies.

3: What else informed the need for slaves?

- European expansion to the Americas was mainly to tropical and semi-tropical areas. This means that several products that were hither unknown to Europeans, such as tobacco, or which “occupied a luxury niche in pre-expansion European tastes” such as gold or sugar, now fell within the ability of Europeans to produce them more abundantly. The problem was that they did not have the labour, and the available supply of free European migrants, indentured servants and prisoners did not half meet the deficit, informing the need for coerced labour. Africa, with the weakest concept of social identity, was the obvious target.

4: Why were the slaves always African?

- A proffered answer has been based on the different values of societies around the Atlantic, and how they defined their identity. As Eltis writes, except for a few social deviants, neither Africans nor Europeans would enslave members of their own societies, but in the early modern period, Africans had a somewhat narrower conception of who was eligible for enslavement than had Europeans. Without this notable dissonance there would have been no African slavery in the Americas, as it was cheaper to enslave other Europeans than send ships to remote and rough Africa. This difference thus explained the dramatic surge of the trade, as Europeans riding the crest of ocean-going technology found more willing sellers in Africa. Essentially, the trade exploited a gap between existing pan-Europeanness and an absent pan-Africanism.

5: Really?

- Yes. The agency of Africans was key, Eltis writes. The merchants who traded slaves on the coast to European ship captains, such as the Vili traders north of the Congo and the Efik in the Bight of Biafra, and the groups that supplied the slaves, such as the Kingdom of Dahomey, the Aro network, and further south, the Imbangala, all had strict conceptions of what made an individual eligible for enslavement. These included constructions of gender, definitions of criminal behaviour, and conventions for dealing with prisoners of war. The make up of slaves purchased on the Atlantic coast thus reflected whom Africans were prepared to sell as much as whom Euro-American plantation owners wanted to buy.

6: Wasn’t there resistance?

- Often. About 10% of slaving voyages experienced major rebellions, increasing the costs of a voyage, meaning less slaves entered the traffic than would have been the case without resistance. Some areas were noticeably more rebellion prone than others – Upper Guinea (Senegambia, Sierra Leone) – and has less slaves shipped away until it became economically justifiable to attempt it anyway.

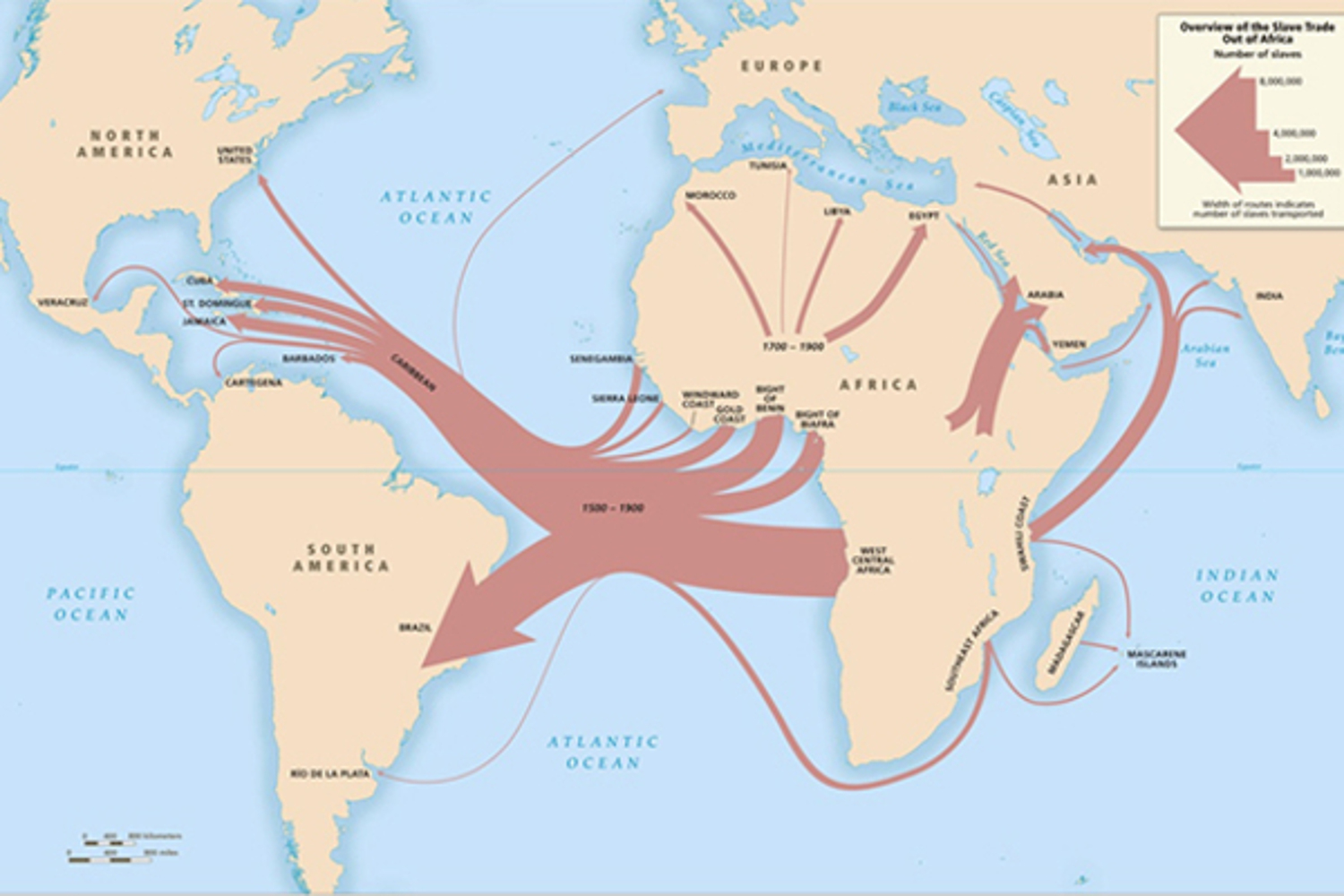

7: What were the main transport routes?

- This map from the database shows the key routes:

8: What informed who went where?

- Wind and Ocean currents in the North and South Atlantic. One vortex lies north of the equator and turns clockwise, the other in the south and turns anticlockwise. The northern wheel was dominated by the English and shaped the northern European slave trade, while the southern wheel handled the brisk traffic to Brazil. The former thus saw slaves leaving mainly from West Africa, while the latter chiefly from Angola, though there were some overlaps of both systems. Brazil and the British Americas received most Africans, while the French brought in half the slaves the British did.

9: A lot is said about Gorée Island in Senegal, which is a major tourist hotspot including for African-Americans. Was it the main point of embarkation for slaves?

- Gorée is the best known, with high profile visitors such as US president Barack Obama and Nelson Mandela having visited and peered through the famous “Door of No Return”. But it is not among the top three embarkation points, which are, in order: Luanda in southern Africa, with 1.3 million slaves dispatched, Bonny in the Bight of Biafra, and Whydah on the Slave Coast. The three ports together accounted for some 2.2 million slave departures.

10: What kind of numbers are we talking about?

- As late as 1820, nearly four Africans had crossed the Atlantic for every European. About four out of every five females that traversed the Atlantic were from Africa. About 12.5 million slaves are estimated to have been embarked on ships. Many died, with only 10.7 million arriving in the Americas, and one in four slaving vessels failed to return to their homeport, victims of sea risks, rebellion and capture. No less than 26% on board were classified as children (under 13 years and less than four feet four inches). Over the 350-year history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, captains purchased more adults (80%) than children (20%). Men were also prime, while African societies tended to retain females.

11: How was it like on a slave ship?

- Tough, Eltis writes. The sexes were separated, kept naked, packed close together, and the men were chained for long periods. Throughout the slave trade era, filthy conditions ensured endemic gastro-intestinal diseases, and a range of epidemic pathogens that, together with periodic breakouts of violent resistance, meant that between 12 and 13% of those embarked did not survive the voyage. The crew faced roughly the same poor survival odds, not to mention the risks of insurrections, successful ones of which were rare. The average duration of the journey was just over two months, though a few voyages sailing from Upper Guinea could make a passage to the Americas in three weeks.

12: Why and how did the trade end?

- Voyages notes what was a lucrative traded ended rather suddenly, despite the obvious economic incentive to continue it. Traffic volume dipped when Brazilian and Cuban authorities—importers— started arresting slave ships at the end of 1850, before other countries clamped down on it. This was mainly due to awareness of the insider-outsider divide in Europe, which meshed with the rising struggle to suppress the trade. Traffic declined gradually in the 1800s after the first action was taken in 1792. Contract labour trade ended in 1917, and the last convict to the Americas returned to France in 1952.

13: How did it affect ethnic and racial identity?

- The sea lanes that sprouted heightened, rather than gradual, cultural contact, leading to first the rise, and then, as perceptions of the insider-outsider divide slowly changed, the fall, of the trans-Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans. It also led to elementary pan-Africanism especially among the victims, as non-elite Africans, who had existed without a concept of Africanness, begun to think of themselves first as part of a African group, say the Yoruba, and then, more widely as blacks. – Lee Mwiti

This article first appeared on the Mail & Guardian’s sister site: mgafrica.com.

- Please visit mgafrica.com for more insight into the African continent.